The Capture of New Orleans

by Charles J. Wexler

The capture of New Orleans on April 29, 1862 gave Union forces under Flag Officer David Glasgow Farragut and Major General Benjamin Franklin Butler control of the Confederacy’s largest port on the Mississippi River. This not only denied Confederate forces a major center of trade and industry, New Orleans’ capture gave Union forces control of the lower Mississippi River valley, which they quickly exploited. Two masonry fortifications guarded the southern approaches on the Mississippi River, Forts St. Philip and Jackson. Both state and Confederate officials felt any attack on New Orleans would originate not from the Gulf but from upstream. Fortifications including Island No. 10, Fort Pillow, and Vicksburg guarded these northern approaches. Defenses at the forts were improved and a collection of warships, locally procured or converted, was added to the defense of the city. The first clash with Union warships, occurred on October 12, 1861 at the Battle of the Head of the Passes with no decisive result. It was also in the early fall that Confederate Secretary of the Navy Mallory inaugurated a major shipbuilding program which included two ironclads to be built to defend New Orleans, the Mississippi, and the Louisiana. A muddled command structure saw a 14 ship River Defense Fleet under Captain John A. Stephenson, Captain William C Whittle commanding New Orleans station without authority over anything afloat and two other naval commanders charged with finishing the two ironclads. While the Confederates organized their defenses, Union Captain David Farragut assembled the West Gulf Blockading Squadron and prepared to attack New Orleans supported by ground forces under Major General Benjamin Butler. Farragut began his attack on April 15, 1862, using a mortar fleet to bombard Fort Jackson and later Fort St. Phillip. On April 24 Farragut moved to pass the forts and attack New Orleans. Opposed by the Confederate River Defense Fleet the two sides inflicted damage and casualties on each other but by dawn on April 24, Farragut had thirteen operational ships upstream past the two forts. On April 25 Farragut reached New Orleans. Local Confederate forces abandoned the city as indefensible and on April 29 Farragut occupied the city. The two forts, bypassed and facing both the mortar fleet and Butler’s troops, surrendered on April 28. Neither Confederate ironclad was fully operational, and both were destroyed by the Confederates to avoid them falling into Union hands. General Butler occupied New Orleans and earned himself the sobriquet “Beast” for, among other reasons, his infamous General Order Number 28 treating any woman who showed disrespect to Union soldiers as a “woman of the town.” In Richmond the loss of New Orleans resulted in the creation of a Joint Special Committee of the House of Representatives to investigate the causes. The capture of New Orleans demonstrated the pitfalls Confederate defenders faced in the first full year of the war. Resource demands from pressing campaigns elsewhere drained New Orleans of valuable soldiers and materials. Divided leadership responsibilities and inter-service rivalries hindered operations and did not seriously consider a seaborne attack from the Gulf. The time needed building a modern navy centered on armored casemate ironclads with limited logistical capabilities meant any delay proved fatal. Union forces, on the other hand, developed a clear plan to capture the city. The Capture of New Orleans shut down the largest Confederate port and secured the lower Mississippi River valley for Federal forces.

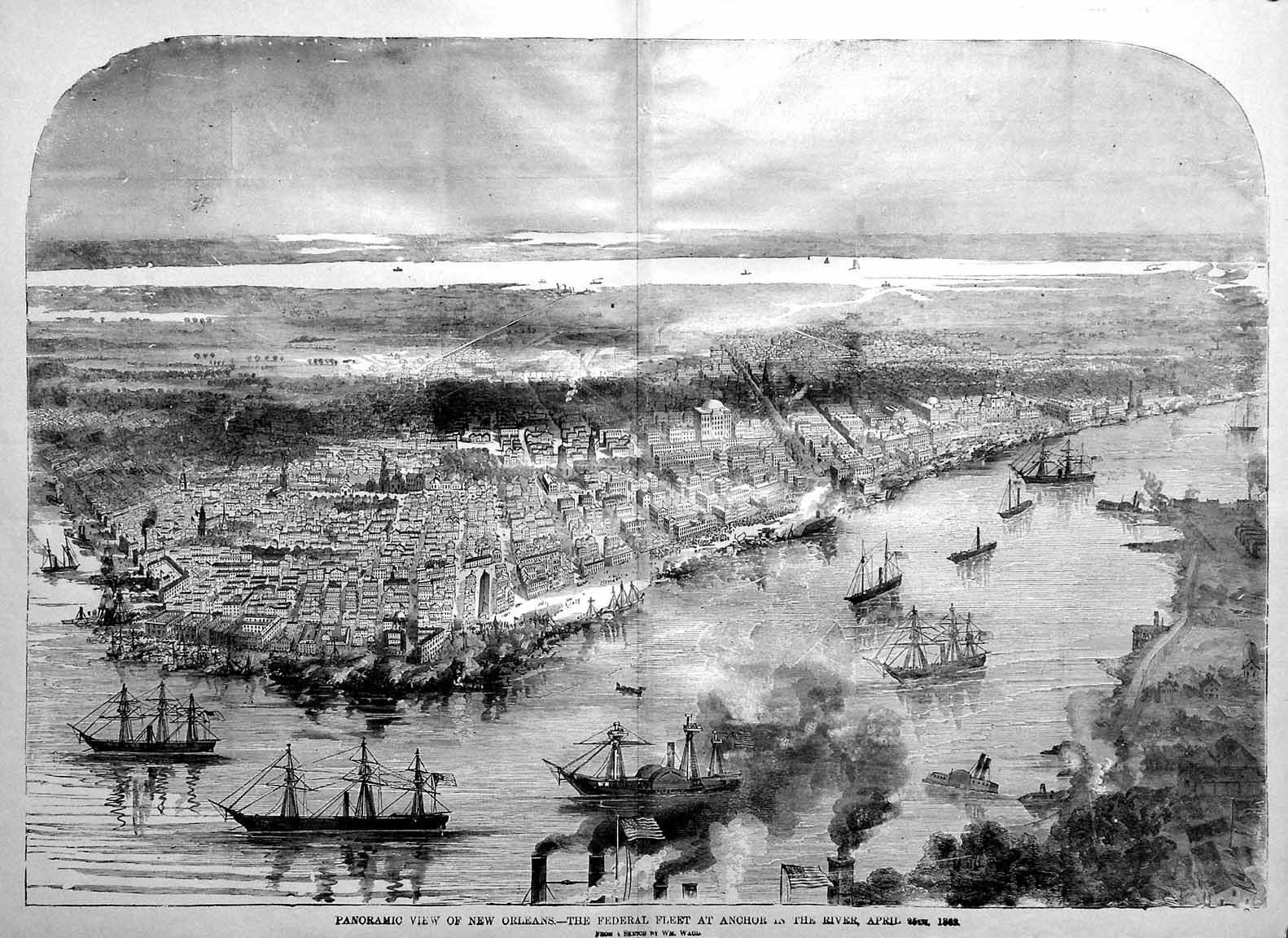

Panoramic View of New Orleans…The Federal Fleet at Anchor in the River, April 25 (1862), From a Sketch by Wm. Waud.

From Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (New York) May 25, 1862.

The capture of New Orleans on April 29, 1862 gave Union forces under Flag Officer David Glasgow Farragut and Major General Benjamin Franklin Butler control of the Confederacy’s largest port on the Mississippi River. The loss of New Orleans, the Confederacy’s most populous city, not only denied Confederate forces a major center of trade and industry, New Orleans’ capture gave Union forces control of the lower Mississippi River valley, which they quickly exploited.

When Louisiana seceded on January 26, 1861, New Orleans already possessed some means toward protecting the Confederacy’s largest port. Two masonry fortifications guarded the southern approaches on the Mississippi River, Forts St. Philip and Jackson. The city though held no organized naval force. On February 13, 1861, Brigadier General P.G.T. Beauregard testified before a military board and argued the city immediately augment its defenses against their “most vulnerable point, the Mississippi River.” He believed that any steamer could easily pass these two forts and they needed immediate reinforcement. This included water-borne obstructions such as floating booms that crossed the river, additional armaments at both locations, and removal of trees to improve the fields of fire. Beauregard’s recommendations went mostly unheeded. Both state and Confederate officials felt any attack on New Orleans would originate not from the Gulf but from upstream. Indeed, fortifications including Island No. 10, Fort Pillow, and Vicksburg guarded these northern approaches. They did not wholly neglect the lower forts. They cleared some fields to improve the sightlines and erected a strong boom that stretched across the Mississippi River near Fort Jackson. Made of cypress logs and weighted down by anchors and chains, this boom lasted from November 1861 until late February 1862. After debris and river currents dislodged this barrier, defenders erected a replacement below Fort Jackson. [1]

Local commanders faced difficulties preparing New Orleans’ immediate defensive works. Brigadier General David Emanuel Twiggs commanded Department No. 1, which comprised Louisiana and southern Mississippi. After his appointment on May 31, 1861, Twiggs collected cannon and started building defensive lines around New Orleans, but at seventy-one his age and health impacted his performance. He subsequently requested a replacement from Secretary of War Judah Benjamin on October 5, 1861. Responsibility and command then fell on the shoulders of Major General Mansfield Lovell. Lovell recruited soldiers and located essential war material to fill these ranks, but they were often removed as quickly as he could train and equip them.[2]

Confederate defensive efforts meanwhile proceeded along other fronts. Captain Lawrence Rousseau arrived in March and bought ships for use in the Confederate Navy. This included steamship Habana, converted into the commerce raider CSS Sumter. Under Raphael Semmes’ command, the Sumter escaped from the Mississippi River on June 3, 1861. Other privateers also sortied from New Orleans, but federal strategies limited their impact. On April 19, 1861, President Abraham Lincoln issued a blockade of the entire Confederate coastline. While it took a significant amount of time for Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles and Assistant Secretary Gustavus Vasa Fox to build, organize, and deploy a navy that could accomplish this task, the first ships quickly arrived off major Confederate ports. On May 27 Commander Charles Henry Poor from the USS Brooklyn informed Major Johnson Duncan at Fort Jackson that he has blockaded the Mississippi River. Joined by the side-wheel steamer Water Witch under Commander David Dixon Porter, the two vessels prevented most privateers from escaping. Semmes’ Sumter proved an exception, where his superior sailing skills allowed him to outrun the Brooklyn and reach the open Gulf.[3]

Emphasis soon shifted toward locally procured warships. Businessman John A. Stephenson purchased and converted the steamer Enoch Train into the ironclad ram Manassas. While underpowered, the Manassas emerged amongst a growing mosquito fleet under the command of Commodore George Nichols Hollins. By August, Hollins commanded six converted steamers in the Mississippi River: the McRae, Calhoun, Ivy, Tuscarora, Pickens, and Jackson. Two other vessels, the Florida and Pamlico, remained on Lake Pontchartrain. These auxiliary warships served as the primary naval force defending New Orleans until the Confederate government began its domestic naval construction program.[4]

Hollins’ mosquito fleet quickly realized its limited potential. Five Union warships had crossed the Mississippi River bar and occupied the Head of the Passes at the Mississippi River delta on October 10. The next day, Lieutenant Alexander Warley commandeered the Manassas at gunpoint from Stephenson off Fort St. Philip. With the Manassas in tow, Hollins proceeded behind with three fire rafts and six gunboats from the Mosquito Fleet. In the Battle of the Head of the Passes, fought in the early hours of October 12, Warley rammed the screw sloop Richmond. This sparked a brief engagement between Hollins’ squadron and Union forces under Captain John Pope. Hollins’ aggressive action drove Pope’s ships toward a local sandbar, where they briefly grounded. Hollins’ limited firepower meant they could only inflict minimal damage upon Pope’s ships, but the victory made Hollins a local hero.[5]

Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Russell Mallory inaugurated a major shipbuilding program in Summer 1861. By September he reached agreements with southern shipbuilders, Nelson and Ada Tift to build the ironclad Mississippi, and the ironclad Louisiana with E.C. Murray. Similar in concept to the converted frigate Merrimack in Hampton Roads, both warships were designed for open ocean operations, contained several inches of rolled iron plate in a casemate design, and held over a dozen cannon as their primary armaments. These shipbuilders quickly however ran into significant problems. Private projects such as the submersible privateer Pioneer, floating batteries conceived by Major General David Eugene Twiggs, and side-wheel gunships such as the General Polk overwhelmed most naval shipbuilders and foundries from supporting these governmental projects. Both projects subsequently required iron plate, machinery, and other requisite products from foundries outside New Orleans, notably from Richmond’s Tredegar Iron Works. This delayed the completion of the Mississippi for months. A strike in November 1861 also delayed these projects “four or five days” after workers demanded higher wages. These delays proved consequential and prevented either ironclad from playing a major role defending their home port.[6]

Changing circumstances in early 1862 impacted local defensive planning. On February 1, 1862, Hollins’ mosquito fleet departed New Orleans to counter growing Union maritime strength upstream. With Hollins gone, Mallory sent three officers to control local naval affairs. He appointed Commander John K. Mitchell in charge of all remaining naval forces with an emphasis on finishing the Louisiana. Commander Arthur Sinclair arrived in March to similarly take charge of the incomplete Mississippi. Captain William Conway Whittle commanded the New Orleans station, but his authority did not extend to anything afloat. Confederate Secretary of War Judah Philip Benjamin meanwhile authorized Lowell to purchase ships on his authority and outfit them with an iron ram, similar to the Manassas. What emerged was a fourteen ship River Defense Force under Stephenson that operated independently from Confederate naval oversight. This muddled command structure, much like the delayed ironclads, proved problematic.

Northern officers quickly placed New Orleans in their crosshairs. Both Fox and Commander David Dixon Porter advocated an attack against the city before discussions began in earnest in November. On November 14,1861 Welles, Porter, and Fox met with Lincoln, Secretary of State William Henry Seward and Major General George Brinton McClellan. They proposed a naval expedition attacking New Orleans from the Gulf of Mexico. Although initially skeptical, McClellan gave his approval upon hearing that this plan only required 10,000 soldiers.[7]

Welles chose Captain David Farragut to head this operation. A somewhat controversial choice, Farragut’s southern background caused some to question his loyalty when the war commenced. Farragut’s foster brother Porter, however, vouched for his ability, which proved sufficient. Farragut assumed command of the newly created West Gulf Blockading Squadron on January 9, 1862, with an emphasis placed on what Welles considered “the great object in view,” New Orleans’ capture. Porter’s politicking ensured he received a significant role within the forthcoming attack as commander of the mortar boat flotilla. Outfitted in New York and Philadelphia and armed with a single 13-inch mortar and other small cannon, these ships would first bombard Fort. St. Philip and Fort Jackson and reduce their defenses. Once the forts were sufficiently weakened, Farragut’s frigates could steam past the forts and head toward New Orleans. A land force under Major General Ben Butler supported Farragut’s operation, and their presence substantially aided Farragut’s success.[8]

Farragut’s squadron overcame substantial obstacles before the attack. The fleet first traversed from bases on the Atlantic coastline around Florida to reach their operational station in the western gulf. Once on station a lack of forward bases hindered any potential resupply should supplies run short. Farragut strove to carry as many munitions and coal as his ships could carry on their initial journey west. Upon arriving on station Farragut encountered his next problem: the shallow Mississippi River bar, which prevented Farragut’s larger warships from entering the river and proceeding toward New Orleans. To cross the bar, the sailors first removed most cannon and material from the ships to reduce their draft. They then either towed them across the bar or found deeper approaches so they could cross under their own power. This process took most of March, which meant Farragut’s ships remained vulnerable during this period.

The absence of any major forward bases soon proved a larger threat than the sandbar. Farragut’s forces suffered substantial resource shortages, particularly coal. Farragut realized this problem when he wrote in February 1862, “Tortugas, the closest resupply point, is too far off to supply ourselves quickly…and to send 400 miles for munitions of war will not do.” Farragut carried extra munitions west with him, but most of the ocean-going warships had minimal coal supplies onboard. Only the presence of Butler’s transports, laden with extra coal, alleviated this issue and restored Farragut’s warships to working order. [9]

One final issue potentially loomed large, the 264-foot Louisiana and 250-foot Mississippi. Their firepower of both smoothbore cannon and Brooke rifles could inflict serious damage upon Farragut’s wooden-hulled warships, and their casemate armored shields provided substantial protection from Federal firepower. Farragut could not counter to this threat with similarly armored craft. The USS Monitor remained in the Chesapeake to counter the CSS Virginia after the March 1862 Battle of Hampton Roads, while Flag Officer Andrew Hull Foote’s ironclads and timberclads slowly traversed the Mississippi. Farragut therefore had to attack as soon as he marshalled his forces, lest he be caught out by the enemy ironclads.

But Confederate forces could not exploit Farragut’s vulnerable squadron. The Federal capture of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson in February 1862 opened Tennessee and western waters to possible Union offensives. This drained New Orleans of both recently raised soldiers and Hollins’ naval squadron. General Ulysses S. Grant’s victory at Shiloh on April 6-7 further stripped away military resources. While Hollins’ ships could not match Foote’s warships in battle, he remained upstream near Island No. 10 until he heard that Farragut had entered the Mississippi River. Hollins left the mosquito fleet and raced back to New Orleans. He offered to attack Farragut’s force, but Mallory instead removed Hollins after he violated his standing orders and departed his command. The ironclads meanwhile still required substantial work. The Louisiana entered the water on February 4, but by mid-April still lacked rudders and other components to steer in the strong river current. The Mississippi only launched in late April with limited machinery and only two cannons installed. Lovell and Mitchell could not depend on fully function ironclads should Farragut start north. Lovell declared martial law in New Orleans in mid-March[10]

With his ships over the sandbar and fueled by sufficient coal, Farragut began his offensive. Porter started preliminary bombardments against Fort Jackson on April 15 from pre-sighted positions three thousand yards away and began in earnest three days later. Porter’s sixty mortar boats, divided into three divisions, fired 216-pound shells about every ten minutes. They anchored behind thick woods, which provided natural cover from Fort Jackson’s responses. Porter’s second division under Lieutenant Walter W. Queen sat exposed on the east bank and drew precise return fire. The following day, Porter repositioned them on the west bank where they enjoyed wooden cover at the expense of their accuracy. Farragut’s warships also provided long-range support, but the strong river current, distance, and Confederate counter-fire limited their effectiveness. One mortar boat sank with no fatalities on April 19. The Oneida suffered nine casualties when three shells punctured her hull, including one on the port side that hit the aft pivot-gun carriage and scattered splinters across the deck. The gunboat Itasca also received light damage from two shells that struck the ship.

Porter’s bombardment caused notable damage. The nearly 3,000 shells fired on April 18 set fire to both the men’s quarters and the citadel at Fort Jackson, which caused Duncan to bring his men in from the parapet to extinguish the flames. The following day the mortars rendered two rifled thirty-two pounders in the water battery and five guns in the fort unusable, and severely damaged the casemates. The forts, however, remained serviceable, and Farragut faced substantial material shortages after only two days of bombardment. On April 20 he wrote, “My shells, fuzes, cylinder cloth and yard to make the cylinders are all out.” Butler’s arrival on April 19 again provided needed supplies, but this led Farragut to remark, “I am dependent upon the army for everything …I am driven to the alternative of fighting it out at once or waiting and resuming the blockade until supplies arrive.” Porter still expressed belief that his mortar boats could incapacitate the fortifications, but Farragut’s logistical difficulties drove him toward an attack. [11]

Before he could proceed, the obstructions that stretched across the Mississippi near the forts needed to be cleared. At 9:00 p.m. on April 20, Captain Henry Haywood Bell led the gunboats Pinola and Itasca against the chain boom. Under Lieutenant Charles H. B. Caldwell, the Itasca made for the east bank and Fort Jackson while Lieutenant Pierce Crosby’s Pinola, with both Bell and torpedo expert Captain Julius Kroel onboard, made for the west back and Fort St. Philip. Under fire from the forts, both craft experienced problems. The explosive conductors onboard the Pinola to detonate explosives placed on the obstructions broke, and the Itasca caught on a hulk and ran aground near Fort St. Philip. Crosby hauled the Itasca free with a 13-inch hawser. Clear from the shore, Caldwell turned upstream and rammed the chain between the second and third boom on the east bank. The Pinola followed the Itasca through, turned around, and at speed broke the chain on the west bank with his bow. Severed, some hulks floated away, and the Union fleet had an unobstructed path beyond the boom.[12]

While Farragut and Porter marshalled south of the forts, Duncan asked Stephenson to deploy fire ships against the enemy, but he first inflicted damage upon his own forces. On April 15 he cut the fire barges away so early that they drifted under the forts, “firing our wharves and lighting us up.” A second attempt five days later, when Bell cut the chain. achieved minimal success. A fire raft floated amongst Farragut's squadron and sparked panic, but only briefly engulfed the gunboat Sciota before the crew extinguished the flames. Stephenson’s failure handling the fire rafts represented a missed opportunity to inflict significant damage against Farragut before he ran past the forts.[13]

Confederate issues extended beyond the River Defense Fleet. Duncan also squabbled with Mitchell, who commanded everything afloat, over repulsing Farragut’s squadron. On April 19 tenders towed the unfinished Louisiana down from New Orleans. Duncan wanted the ironclad below the chain and Fort Jackson to engage both Porter’s mortar schooners and Farragut’s warships as they first approached. Mitchell however wanted the Louisiana safely upstream to continue work on her machinery. Heated discussions over her placement continued up until Farragut’s advance, while the Louisiana remained upstream. This highlighted the disjointed Confederate command structure exhibited throughout the region with various independent groups near the fortifications and directly hindered New Orleans’ maritime defense. When Farragut attacked at 3 on April 24, Mitchell commanded only four warships assembled above the boom: the Louisiana, the Manassas, and the steamers McRae and Jackson. Of these, the Jackson was deployed to the upper canals to help dispute Butler’s landing. Stephenson commanded six gunboats of the River Defense Force under the auspices of the War Department, although neither Duncan nor Mitchell wanted Stephenson under their respective commands. The Louisiana State government meanwhile controlled two gunboats above the Manassas on the west bank, with other tugs, tenders, and fire rafts under assorted jurisdictions nearby.[14]

Farragut detailed his plan of attack to his ship captains on April 23. Porter’s schooners would bombard Fort Jackson at a rapid pace, supported by the sailing vessel Portsmouth. Farragut divided his remaining seventeen ships into three divisions. Captain Theodorus Bailey led the van in the First Division in the Cayuga. The Pensacola, Mississippi, Oneida, Varuna, Katahdin, Kineo, and Wissahickon then followed. Farragut followed with the Center Division on his flagship Hartford, along with the Brooklyn and Richmond. Captain H. H. Bell brought up the rear in the Third Division with Sciota, Iroquois, Pinola, Itasca, and Winona. Bailey’s ships would target Fort St. Philip as they passed on the eastern side of the river, while Farragut and Bell’s divisions targeted Fort Jackson. After a small launch confirmed the river remained clear, Farragut called his crews to quarters just after midnight on April 24.

Delays onboard the Pensacola prevented Farragut’s departure until 3:30 a.m. The Cayuga led the First Division upriver in a single file toward the gap in the boom. Within ten minutes gunners under Captain William B. Robertson of the 1st Louisiana Artillery spotted movement from the water battery below Fort Jackson. Opening fire on Farragut’s ships, both fortifications quickly joined in against the Cayuga and those that followed behind. The smoke from both Union and Confederate cannon fire obscured the darkened river, which notably reduced visibility and hindered navigation onboard Farragut’s warships. The Pensacola, the second ship in line, veered toward the center of the river in front of Farragut’s Center Division. The other ships of the First Division somewhat haphazardly followed and disrupted the advance. Farragut did not wait for the final ship of the First Division, the Wissahickon, to move before he advanced in the Hartford. The smoke also caused the Brooklyn to run into the Kineo. Bell’s Third Division followed the Richmond beyond the barrier and proceeded relatively unmolested, particularly when compared to flagship Hartford. A fire raft guided by the tugboat Mosher engulfed the port side of the Hartford after the flagship ran aground above the water battery.

Few Confederate steamers directly engaged Farragut’s force that evening. The Manassas, under Lieutenant Alexander Warley, attacked multiple frigates as they passed by with help from the river’s four-knot current. Starting above Fort St. Philip, Warley first made for the Pensacola. He missed the Pensacola with the iron ram and as he passed nearby the Pensacola unleashed a broadside. Lieutenant. George Dewey onboard the sidewheel frigate Mississippi then spotted the Manassas and tried running down the smaller ship. Warley though used the current to avoid a head-on collision and gashed the Mississippi above the waterline. He then rammed the Brooklyn, driving the starboard armor chain into the hull below the waterline. The McRae engaged the First Division with six 32-pounders and a 9-inch shell gun and had a brief but violent exchange at close range with the gunboat Iroquois. Both ships traded shell, canister, and grape rounds at close range. Damaged, McRae briefly pursued Farragut before retreating toward Fort St. Philip. The Governor Moore from the River Defense Fleet attacked the gunboat Varuna near Quarantine. After a short engagement, the Governor Moore rammed the Varuna and broke her hull. The R. J. Breckinridge of the River Defense Fleet also hit the Varuna on the port beam. The heavy damage sank the gunboat soon after she ran ashore. The Varuna however had wounded the Governor Moore with a broadside of eight-inch shells. Governor Moore Captain Beverly Kennon blew up the Confederate gunboat after re-engaging most of Farragut’s surviving fleet. By dawn thirteen of Farragut’s ships remained operational and had successfully passed the forts.

Farragut’s run past the forts kept casualties at a surprising minimum. Onboard 36 sailors died and 135 suffered wounds while the ships passed the forts. When combined with 2 deaths and 24 wounded prior to April 24, this meant a total of 38 fatalities and an additional 159 wounded. Many ships suffered notable damage. The gunboat Varuna ran aground and was subsequently sunk. A shot pierced the Itasca’s boilers and put her out of action. Two other vessels did not pass the boom and remained with Porter’s mortars. The Hartford received substantial attention during the fight. Thirty-two shots hit the flagship and disabled two cannons amongst other damage. The Hartford also rammed the gunboat Kimeo, which received nine hits. Both the Brooklyn and Mississippi leaked from the Manassas ramming and enemy gunfire. The Richmond, Pensacola, Cayuga, and Iroquois escaped with only light damage from Confederate gunners. Confederate defenders also experienced light casualties during the bombardment, with only 11 dead and 39 wounded in the forts. Confederate forces afloat suffered heavier losses. Only one of the River Defense ships survived the initial engagement of April 23-24, with the rest either ran aground or destroyed. Mitchell’s warships similarly suffered, with the Louisiana afloat but needing substantial repairs. [15]

Farragut quickly pressed his advantage. He briefly paused at Quarantine so his men could rest and repair their ships. The Manassas followed Farragut upstream but was caught out by the Mississippi and Kimeo. The two attacked at close range and compelled Warley to run aground and abandon ship. Men from the Mississippi boarded and torched the Manassas, which floated past both the forts and Porter’s mortar craft. At 10:00 a.m. eleven of Farragut’s remaining ships then progressed forward in two columns, stopping for the night south of English Turn where Confederates had placed some batteries.

The following morning, Farragut’s squadron started at 4:00 a.m. They passed the remaining fire rafts, obstructions, and batteries and reached New Orleans by early-afternoon. As they approached, they witnessed the wanton destruction in the panic caused by their arrival. Farragut remarked, “But I must say I never witnessed such vandalism in my life as the destruction of property; all the shipping, steamboats, etc., were set on fire and consumed.” This included the unfinished ironclad Mississippi. The Tifts quickly launched their ironclad upon hearing Farragut reached Fort Jackson in an attempt to tow her to safety. The strong currents and lack of completed machinery prevented this from occurring. They instead torched the Mississippi so it would not fall into enemy hands. The burning hulk floated downstream, passing Farragut’s ships early on April 25. Lowell meanwhile effected an evacuation of most government property and sent them toward Camp Moore, seventy-eight miles away.[16]

The surrender of New Orleans took four days after Farragut’s arrival. He sent a party led by Captain Bailey on the afternoon of April 25 to demand the city’s surrender. Mayor John Monroe claimed that under martial law only General Lowell could make that determination. Lowell initially refused the surrender request and stated that he had fifteen thousand troops at his disposal. Lowell however suggested that he evacuate and turn the city over to the mayor to prevent a bombardment of the city by Farragut’s men. Lowell subsequently made for Camp Moore with his remaining soldiers. On April 26, Farragut again requested the city’s surrender, and sent sailors from the Pensacola to raise the US flag over the United States Mint building. Mobs met Farragut’s men on both days with anger and threatened violence. Men tore down the US flag from the Mint soon after it went up on April 26 and brought it to City Hall. Despite the mob’s presence, Mayor Monroe knew New Orleans was undefended after Lowell’s withdrawal. He subsequently informed Farragut, “Come and take the city; we are powerless.” Farragut waited until April 29 to formally occupy the city, landing sailors under Captain H. H. Bell and Captain Albert Kuntz along with a marine detachment. Bell first proceeded to the Customs House, where he raised the Stars and Stripes, and then headed to City Hall. There, he hauled down the Louisiana state flag, signifying the city’s occupation.[17]

While Farragut steamed toward New Orleans the two forts remained uncaptured. Fort Jackson suffered substantial damage and the Louisiana could not move, but Fort St. Philip escaped relatively unscathed. Colonel Higgins from Fort Jackson refused Porter’s surrender request on the morning of April 25, sparking Porter into further action. He resumed bombarding the forts and placed two schooners in the bayou behind Fort Jackson. He then suggested Butler place soldiers near Fort St. Philip. Butler subsequently landed the 26th Massachusetts and portions of the 4th Wisconsin Volunteers and 21st Indiana behind Fort St. Philip from the light-draft Miami and thirty small craft. With both forts surrounded Porter demanded Higgins’ surrender on April 27 without any success. Butler’s soldiers helped spark what unfolded that night at Fort Jackson. That evening about three hundred men in the garrison at Fort Jackson mutinied and spiked their guns. While loyal units like the St. Mary Cannoneers and officers tried interceding they did not prevent this successful mutiny. These mutineers sought escape from Confederate service and potential Confederate reprisals. While some from the Saint Mary’s Cannoneers accepted parole and continued fighting in the Confederate Army, most mutineers swore loyalty to the Union. Some returned to New Orleans, while others worked as laborers at Fort Jackson for the Union army. A few even enlisted in Union regiments despite the possibility of execution for desertion and mutiny if Confederate unions captured them on the battlefield.[18]

Cut off from outside communication, and with Mitchell still working on the Louisiana’s machinery, both forts surrendered to Porter and the mortar flotilla on April 28. This ensured the Navy received sole credit for both the capture of New Orleans and the capitulation of the forts. After garrisoning the forts, Brigadier General John Wolcott Phelps remarked how they were “abundantly provided with all the materials…necessary for a long defense.”[19]

The surrender of the forts was not without controversy though. As Higgins and Duncan only acted on behalf of the fortifications, Warley and Mitchell decided to destroy the ironclad to prevent its capture. The Louisiana blew up near the water battery of Fort St. Philip. The force of the explosion blew off the casemate and the resulting iron shrapnel from the casemate killed one. The destruction enraged Porter given it occurred under a flag of truce. Only after the Louisiana’s destruction did Mitchell surrender his remaining ships to Porter. The surrender of the forts solidified Union control over New Orleans and completed the capture of the city.

The capture of New Orleans quickly resonated as a major Confederate setback within the western theater. Earlier defeats at Forts Henry and Donelson, Island No. 10, and Shiloh had left Confederates reeling. Confederate desertions of local soldiers as Lovell ordered their retreat to Camp Moore further compounded the city’s capture and demonstrated limited commitment toward the Confederate cause amongst recently recruited soldiers. Louisiana was now laid open to a Union advance. Farragut seized the initiative and moved north to capture the remaining Confederate outposts on the lower Mississippi River. He reached Baton Rouge on May 9 and three days later his forces captured Natchez, Mississippi. When coupled with advances against Memphis and the abandonment of Corinth in early June, this left Vicksburg, Mississippi as the sole remaining Confederate installation on the Mississippi River. Capturing Vicksburg, however, proved much more difficult. Farragut arrived off Vicksburg on May 18 with fifteen hundred soldiers but could not compel the city’s surrender. He remained until late July, when lower water levels compelled the return of his larger warships to the Gulf with Vicksburg still in Confederate control, where it would remain until July 4, 1863.[20]

As Farragut headed upstream Butler’s soldiers occupied New Orleans. He swiftly declared martial law on May 1 to impose military rule over the city and asked that civilians swear loyalty oaths to the United States. Butler worked toward rebuilding New Orleans and the city’s diverse population, secured food for poor citizens and established roving labor gangs to improve the city’s public health. Other actions angered elite whites and garnered him the nickname “Beast.” After his soldiers received “repeated insults from the women,” Butler targeted elite women in his May 15 General Order No. 28. This stated any woman that disrespected any soldier would be treated as a “woman of the town.” He tried and hanged William Munford in late May after Munford tore down the U.S. flag from the Mint on April 26. In July, Butler established a commission that seized property under the Second Confiscation Act throughout the Department of the Gulf.[21]

Blame over New Orleans’s capture quickly spread to Richmond. In his after-action report, Lowell blamed his defeat on three factors: the lack of heavy guns defending the forts, the high level of the Mississippi River which swept away any river-borne obstructions, and the Navy’s failure to complete the Mississippi and Louisiana in a timely fashion. Angered at both New Orleans’ loss and Mallory’s overarching conduct as Secretary of the Navy, the Confederate Congress opened proceedings against Mallory. On August 27, 1862 the House of Representatives authorized a ten-man Joint Special Committee investigating the Navy Department and fixated on New Orleans. The investigation examined what fueled the city’s downfall but left Mallory still in his post.[22]

The capture of New Orleans demonstrated the pitfalls Confederate defenders faced in the first full year of the war. Resource demands from pressing campaigns elsewhere drained New Orleans of valuable soldiers and materials. Divided leadership responsibilities and inter-service rivalries hindered operations and did not seriously consider a seaborne attack from the Gulf. The time needed building a modern navy centered on armored casemate ironclads with limited logistical capabilities meant any delay proved fatal. Union forces, on the other hand, developed a clear plan to capture the city. Farragut’s selection as leader of the naval attack on New Orleans, proved brilliant in hindsight, and his success heading the West Gulf Blockading Squadron made him the top naval commander of the war. His capture of New Orleans shut down the largest Confederate port, secured the lower Mississippi River valley for Federal forces, and served as a significant milestone in a series of western Union successes in Spring 1862.

- [1] United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 vols. in 128 parts (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 1, p. 500-1 (hereafter cited as O.R., I, 1, 500-1).

- [2] O.R., I, 53: 748.

- [3] Chester G. Hearn, The Capture of New Orleans, 1862 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996), 47.

- [4] The term mosquito fleet referred to the fact that Hollins’ ships were lightly armed auxiliary warships, converted steamers that could pester put perhaps not inflict significant damage toward purpose-built federal warships.

- [5] Hearn, The Capture of New Orleans, 85-86; United States Navy Department, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, 30 vols. (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1894-1922), Series I, volume 16, p. 703-5 (hereafter cited as O.R.N., I, 16, 703-5); O.R.N., II, 1, 472.

- [6] O.R.N., II, 1, 554-5, 756-7.

- [7] Hearn, The Capture of New Orleans, 97-106.

- [8] O.R.N., I, 18, 3-5, 8, 25-26.

- [9] O.R.N., I, 18,29.

- [10] O.R.N., II, 1, 473-7, 487-90, 519-20.

- [11] O.R.N., I, 18, 136.

- [12] Ibid., 138.

- [13] Ibid., 265.

- [14] “The Opposing Forces in the Operations at New Orleans, LA,” in Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, eds., Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Being for the Most Part Contributions by Union and Confederate Officers. Based Upon “The Century War Series”, 4 vols. (New York: The Century Co. 1884-1888), based on “The Century War Series” in The Century Magazine, November 1884 to November 1887, 2:73-75.

- [15] O.R., I, 6, 528, 550; Hearn, The Capture of New Orleans, 241.

- [16] O.R.N., I, 18,153; O.R., I, 6, 511-512.

- [17] O.R., I, 1, 514-515; Albert Kautz, “Incidents of the Occupation of New Orleans,” in Johnson and Buell, Battles and Leaders, 2:91-94. Lowell did offer on April 28 to return with his men but feared in doing so it would spark a bombardment from Farragut’s warships on the city.

- [18] Michael Pierson, Mutiny at Fort Jackson: The Untold Story of the Fall of New Orleans (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 17-21, 114-119, 129-131, 144-153; Terry L. Jones (ed)., The Civil War Memoirs of Captain William J. Seymour: Reminiscences of a Louisiana Tiger (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1991), 32-34.

- [19] O.R., I, 6, 504-5, 509.

- [20] Pierson, Mutiny at Fort Jackson, 121-127.

- [21] O.R., I, 53, 526-7; O.R., I, 6, 720-4.

- [22] O.R., I, 6, 517-8; O.R.N. II, 1, 431-809.

If you can read only one book:

Hearn, Chester G. The Capture of New Orleans, 1862. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996.

Books:

Browning, Robert M., Jr. Lincoln’s Trident: The West Gulf Blockading Squadron During the Civil War. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2015.

Duffy, James P. Lincoln’s Admiral: The Civil War Campaigns of David Farragut. New York: Wiley, 1997.

Dufour, Charles L. The Night the War Was Lost. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990.

Hearn, Chester G. When the Devil Came Down to Dixie: Ben Butler in New Orleans. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1997.

Hess, Earl. The Civil War in the West: Victory and Defeat from the Appalachians to the Mississippi. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Johnson, Robert Underwood and Clarence Clough Buel, eds. Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Being for the Most Part Contributions by Union and Confederate Officers. Based Upon “The Century War Series”, 4 vols. New York: The Century Co. 1884-1888, based on “The Century War Series” in The Century Magazine, November 1884 to November 1887, 2:13-102.

Pierson, Michael D. Mutiny at Fort Jackson: The Untold Story of the Fall of New Orleans. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

United States Navy Department. Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, 30 vols. Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1894-1922, Series I, volume 18, Series II, volume 1.

United States War Department. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 vols. in 128 parts. Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901, Series I, volume 6.

Organizations:

Fort Jackson National Historical Monument

The Plaquemines Parish Government operates the Fort Jackson Museum & Welcome Center located at 38039 Highway 23, Buras, LA 70041. For information on visiting hours please call 504-393-0124.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.