The Confederate Constitution

by Donald L. Stelluto, Jr.

After a Confederate Provisional Constitution was drafted in early 1861, the Confederate Permanent Constitution was approved March 11, 1861 by five of the seceded states. Though it retained the overall organization and many features of the U.S. Constitution, the Permanent Confederate Constitution differed noticeably from its forbear, incorporating changes that its southern framers hoped would eliminate the abuse of government power, facilitate reform and efficiencies, incorporate parliamentary features, and restore the mid-century American understanding of federalism (the balance of government power between state and national governments). Significant revisions were made in Articles I, II, and V, with more than half of all changes in the southern constitution made in Article I, reflecting the framers’ objectives to prevent self-expansion of congressional powers while maximizing efficiency. Moreover, the various rights included in the U.S. Constitution’s Bill of Rights were incorporated into the text of the Constitution rather than appearing as a separate section. The constitution was hailed in the North for its innovations. Though a Confederate Supreme Court was envisaged in the constitution, the court was never formed so interpretation of the constitution was left to state supreme courts. Provisions to enhance democracy and sovereignty included election of senators by state legislators, easier provisions for impeachment of officials including federal judges, and easier provisions for amending the constitution. The framers included mechanisms designed to provide limited but effective government. Among these were the removal of the General Welfare clause which had been used in the antebellum period to expand national power, the requirement that every bill cover one subject only to be included in the title of the bill, and that appropriation bills specify the exact dollar amount to be appropriated. During the war, Confederate courts consistently interpreted the constitution’s provisions to limit national power. The constitution also clarified the concept of dual federalism in which the constitution was understood as a compact among the states, delegating only specific enumerated powers to the national government and retaining those not delegated for the individual states. However, the constitution did not provide for secession by individual states and judgements made by state supreme courts largely supported the national government, undercutting the idea of States’ Rights which had formed part of the rationale for the creation of the Confederacy. While the constitution limited national power it also sought to make the national government a more effective managerial government. The president was appointed for one six-year term in order to free him from party influence necessary for re-election and act as an executive of the whole people. A line item veto gave the president the power to curtail special interest legislation. The president was empowered to initiate appropriation bills and such bills would only require a simple majority unlike congressionally initiated appropriation bills which require a two thirds majority. The president was given constitutional removal powers over cabinet members, diplomats and other civil officers. Executive-legislative collaboration was improved by providing for cabinet representation and participation in congressional debates on matters relating to cabinet members’ portfolios. Recess appointments of any person previously rejected by the Senate were proscribed. The constitution included specific provisions to protect slavery though it did prohibit the African slave trade. A Confederate constitutional order never existed during peacetime, as it did for the U.S. Constitution of 1787. If it had, a more objective understanding of the southern charter, the regular operation of government it proposed, and a more direct comparison with the U.S. Constitution might be possible. The Confederate framers developed a constitution they hoped would reform the constitutional and political order they had known while in the Union which provides an historically important American constitutional moment.

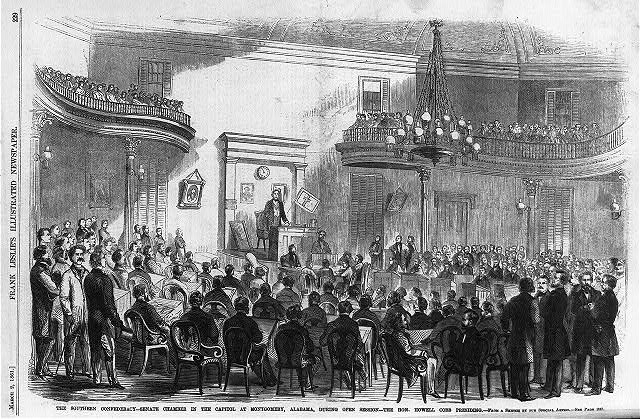

The Southern Confederacy – Senate Chamber in the Capital at Montgomery, Alabama.

Picture from: Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, March 2, 1861, page 229.

During the years leading up to the Civil War, southerners frequently alleged the corruption of American constitutional government under “a violated Constitution,” complaining particularly about the expansion of national power, the use of Presidential privilege and patronage, a spoils system that fostered government inefficiency, the erosion of the federal system, and consolidated national government power.[1] On February 8, 1861, following the secession of seven southern states, Confederate framers signed a provisional constitution for their new nation and the next day began drafting a permanent constitution, convening the Provisional Confederate Congress for ten days as a constitutional convention. A twelve-man committee comprised of deputies from the states, including South Carolinians James Chestnut, Jr. and Robert Barnwell Rhett, Sr., Georgian Thomas Reade Rootes Cobb, and Mississippian Wiley Pope Harris, drafted the national charter that embodied their political dissent and proposed to remedy the antebellum flaws and abuses they alleged under the U.S. Constitution.[2] Their Permanent Constitution was approved on March 11, 1861 and sent to the states for ratification. By March 26, 1861, five states had ratified the document meeting the minimum requirement for ratification. Eventually, each state represented in the Confederacy ratified the Permanent Constitution.[3]

Though it retained the overall organization and many features of the U.S. Constitution, the Permanent Confederate Constitution differed noticeably from its forebear, incorporating changes that its southern framers hoped would eliminate the alleged abuses of government power, facilitate reform and efficiencies, incorporate parliamentary features, and restore the mid-century American understanding of federalism (the balance of government power between state and national governments). Significant revisions were made in Articles I, II, and V, with more than half of all changes in the southern constitution made in Article I, reflecting the framers’ objectives to prevent self-expansion of congressional powers while maximizing efficiency.[4] Moreover, the various rights included in the U.S. Constitution’s Bill of Rights were incorporated into the text of the Constitution rather than appearing as a separate section.

Though the Confederate nation was born out of secession, there was no right to secede in their national charter. During the constitutional convention, James Chesnut proposed that nullification be recognized as an appropriate remedy for disputes between states and the national government, but this idea was rejected. Benjamin Harvey Hill of Georgia tried to introduce secession as remedy for such disputes after a period of waiting, with Chesnut seeking to amend the proposal to include a simple right of secession, but both proposals were tabled and never raised again.[5] If states’ rights was the principal constitutional principle and the dominant political philosophy of the Confederacy, as has often been argued by historians, the constitutional convention, and subsequent wartime constitutional cases before state courts, provided excellent opportunities to assert this principle. The rejection of a constitutional right to nullification or secession may seem contradictory given that southern states had wielded secession just months earlier as a means for leaving the Union. Yet, many Confederate framers and their constituents were confident that improvements incorporated into their new constitution restored American constitutionalism and introduced innovations that addressed antebellum constitutional conflicts and militated against a future need for secession.

Innovations in the Confederate Constitution were viewed by southerners as a much-needed reform of American constitutional government. Alabamian Robert Hardy Smith, a member of the southern convention, in March of 1861 extolled the virtues of the new charter, explaining “we may, I think, congratulate ourselves that grave errors have been corrected, and additional hopes given for the preservation of American liberty.”[6] Georgian Howell Cobb, President of the Confederate Provisional Congress and a member of the Constitutional Convention, noted for his constituents its adherence to American constitutional principles, and concluded that it would become much admired: “What ever [sic] may be the criticism of the hour upon the Constitution we have formed, I feel confident that the judgment of our people, and indeed of the world, will in the end, pronounce it the ablest instrument ever prepared for the government of a free people.”[7] In February of 1862, as the provisional government and constitution transitioned to the permanent Confederate government and constitution, The Intelligencer (Atlanta) declared “We are now seeking to create a government that will be nearer perfection than the one we have left.”[8] Days later, the New Orleans Daily Picayune stated that the Confederate Constitution was “a clear, calm, stately manifesto of the cause which impelled eight millions of free people to withdraw from a Government, which had, by a long train of abuses and usurpations...evinced a design to reduce them under absolute despotism.”[9]

Admiration for the southern charter extended into the North. A New York Herald editorial praised the new constitution for its “very important and most desirable improvements.” The Northern newspaper echoed southern confidence in these innovations to address the nation’s constitutional ills, adding “the invaluable reforms enumerated should be adopted by the United States, with or without a reunion of the seceded States, and as soon as possible.”[10] So appropriate and timely were the new features of the Confederate Constitution that a Harper's Weekly editorial predicted, “Most of them would receive the hearty support of the people of the North.”[11]

As with the U.S. Constitution, judicial review was the means for explaining provisions and principles in the Confederate Constitution.[12] Beginning in 1862, conscription and other wartime measures prompted a series of cases that provided a unique opportunity to have the Confederate Constitution studied and enunciated by the courts. However, while Article III provided for a Confederate Supreme Court, because the southern Congress could not agree on the court’s membership, a national supreme court was never formed.[13] During the war, lower-level Confederate district courts adjudicated sequestration, admiralty, and prize cases as well as some constitutional questions related to conscription. But, because the Confederate national system of courts included no intermediate level of appellate jurisdiction, litigants in constitutional cases before Confederate district courts risked leaving themselves without any opportunity for appeal, at least until such time that a Confederate Supreme Court was formed. In the absence of a national supreme court, litigants therefore filed their constitutional cases in state courts where they could, if necessary, appeal adverse decisions.

In cases that challenged conscription statutes and statutory exemptions under them, the chief means for enabling state courts to assert jurisdiction was by issuing a writ of habeas corpus.[14] The writ could be issued by a state court or an individual state supreme court justice and it had the effect of compelling civil or military officials to produce the body of the individual to the court without delay so that the court could determine the lawfulness of the detention of the petitioner and whether they had been illegally deprived of their personal liberty.[15] Ironically, with the greater number of constitutional cases in state courts and the frequency with which state court justices held the constitutional decisions of other jurisdictions authoritative or advisory, the more extensive adjudication of Confederate constitutional issues and enunciation of the Confederate Constitution were to be rendered principally by state supreme courts during the war.

Democracy and Sovereignty

For Confederate framers, secession and the creation of a new American nation presented an opportunity to resolve significant antebellum political differences, to introduce revisions designed to foster greater political discussion, and to better implement the political will of the people, especially among those elected to political office.[16] In Article I, Section 3, clause 1, Confederate framers revised procedures for electing senators, who were to be chosen for a six-year term by state legislators who had recently been elected to office, just prior to the start of a new senatorial term. Freed from possible corruption likely to result from incumbencies, state legislators, it was believed, could better select senators who would reflect the will of the people, having just encountered and been elected by the same voters.[17] To ensure that Confederate officials, including federal judges, reflected the will of the people and to prevent them from acting with impunity, Article I, section 2, paragraph 5 of the new charter provided for their impeachment by a two-thirds vote of both branches of the legislature in the state in which they served. The practical effects of this provision were to reduce allegiances born out of patronage and to remind Confederate officials that they were, at all times, the people’s servants.[18] To ensure that the democratic process remained a privilege of Confederate citizens only, who were assumed to be fully invested in the decisions of the political community, Article I, section 2, clause 1 prohibited foreign-born persons from voting in state or national elections unless they had become Confederate citizens.

Confederate framers also sought to fashion a more democratic procedure for amending the national charter under Article V. Fearing the broad interpretative power of Congress to use amendments to redraft the Constitution, the framers eliminated the ability of Congress to initiate the amendment process in favor of the states. In Article V, section 1 they created a more specified process in which the scope of constitutional amendments was limited; only those amendments proposed by states could be considered by a convention and the threshold was lowered so that any three states could demand a national convention. The intent was to encourage greater discourse among the people on political differences within the Confederacy and to foster this process early and with the inclusion of minority views. With this broader political discussion of the proposed amendments, Confederate framers expected to encourage the development of a consensus among the people. Accordingly, they also lowered the threshold for ratification, substituting a two-thirds vote of the state legislatures for the three-fourths vote required under Article V of the U.S. Constitution.[19]

Limited but Effective Government

Southern framers considered the broad, vague charge of the U.S. Constitution’s General Welfare clause a principal mechanism by which national legislators in Congress had expanded national power. This, they alleged, had been done repeatedly during the 19th century, in the form of taxation, the erection of protectionist tariffs that interfered with free trade, and the creation of roads, canals, harbors, and other internal improvements that spent tax revenues for the benefit of specific communities rather than the nation.[20] Such practices had long prompted complaints about congressional fiscal irresponsibility and the influence of special interests.[21] Southerners therefore eliminated the clause from where it had existed in the preamble of the U.S. Constitution and in the Article I, Section 8 enumeration of powers granted to Congress. In so doing, Confederate framers hoped to restrict congressional power to only those powers and duties specified in the Constitution. According to Congressman T.R.R. Cobb, the elimination of the clause promoted greater “economy” in contrast to the “extravagance and corruption of the old Government.”[22]

To promote greater legislative accountability, Article I, section 9, clause 20 required that every bill before Congress be related to one subject only, which was also to be expressed in the title of the bill. This was a development designed to prevent the antebellum abuse of attaching riders to bills.[23] In another move to promote specificity and to eliminate wasteful spending Article I, Section 9, clause 10 of the new constitution required that bills of appropriation specify the exact dollar amount requested and to include the purpose for the appropriation. This was designed to prohibit Congress from paying additional compensation after contract terms and prices were established. Moreover, the phrase “post-roads” had been interpreted broadly during the antebellum period in order to fund and build costly federal road projects with only limited or occasional use for the delivery of the mail. Guided by their commitment to limited government and greater specificity, Confederate framers substituted the phrase “post-routes” in the language of Article I, Section 8, clause 7 in order to limit public funding for only those roadways designed and required for specific postal routes and used for regular mail delivery, ending what they considered to be an expansive and wasteful antebellum practice.[24] Antebellum constitutional experiences also led Confederate framers to restrict Congress from expanding its own powers beyond those listed in the Constitution. In Article I, Section 8, clause 1, they limited the taxing power, permitting only those taxes necessary to pay government debts, provide for the common defense, or pay for the business of the government. The clause also prohibited the national government from issuing bounties, protective tariffs, or initiating internal improvements.

Wartime cases raised questions about whether war might be a sufficient reason for expanding national government power. Despite the demands of war that could invite the suspension of such constitutional limitations, as occurred in the North, most southern state jurists upheld constitutional limitations.[25] In the 1863 Alabama case of Ex Parte Hill, In Re Willis, et al. the state’s high court rejected an expansion of power by the Richmond government, holding that the national government was limited to the proper exercise of only those powers delegated under the Constitution and that vigilance was necessary “to prevent it from enlarging its powers by construction.”[26] In the 1864 case of Ex Parte Abraham Mayer, Texas Associate Justice Reuben A. Reeves extended the prohibition, holding that the primary responsibility of the Confederate government was to fulfill the purposes for which it had been created and that any expansion of the national power, especially under a claim that wartime needs required it, would stretch national government power beyond the Constitution and “pervert the power which was intended for the protection and common defense of all the states into an engine of self-destruction.”[27]

The constitutional authority of the Confederate government to impress foodstuffs, war material, and slaves as military laborers was never questioned during the war, under constitutional delegations of war power and eminent domain.[28] Wartime cases, though, did raise more technical questions about how the national government, particularly the Army, exercised this power. Following the first impressment act in March of 1863,[29] cases were brought in the state supreme courts of Georgia, Alabama, and Florida. In the Georgia case of Cox & Hill v. James F. Cummings,[30] the court, borrowing from a Virginia hay impressment case, refused to provide Congress special powers because of wartime exigencies, limiting it to those enunciated in the Constitution. Declaring that “Congress is but the creature of the Constitution,” the court required that Congress satisfy the test for a constitutional takings under Article I, Section 9 and it rejected any claim that Congress could promulgate legislation depriving owners of their property (sugar, in this case), “even for public use, unless adequate compensation is secured by the law.”[31] Moreover, constitutional authority was not enough; the Confederate government had also to observe constitutional forms and limitations in the proper exercise of its powers. A year later, in another sugar impressment case, the court extended these limitations, declaring that the “necessity” standard argued for by the Confederacy was not included within the Article I, Section 9, Clause 16 language that conveyed the impressment power upon the Confederate government. The validity of an impressment officer’s actions would be measured by constitutional authority as well as by the statutory language of the Impressment Act.[32] One year later, in 1864, the Alabama Supreme Court adjudicated the Confederate impressment of railroad rolling stock in the case of Alabama and Florida Railroad Co. v. Kenney.[33] According to the court, under the Constitution, the standard to be applied for a takings case was whether it had been undertaken for the national common good, for this common good was what the national government was charged to preserve. The court’s emphasis upon safeguarding the common good, expressed as “’the mutual necessities of the individuals about to constitute a political community’” provided a doctrinal structure for deciding impressment cases.[34] In these impressment decisions, state courts revealed a commitment to prevent the national government from overstepping its constitutional bounds, regardless of the demands of war.

Even though Confederate framers limited the scope of general authority through the elimination of the General Welfare clause, they did not intend to make the national government powerless in fulfilling the duties and responsibilities assigned to it in the Constitution. Confederate framers retained the Necessary and Proper clause under Article I, Section 8, clause 18, empowering Congress to “make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers” listed earlier in the article. By so doing, a Congress prohibited from expanding the scope of its responsibilities was provided with broad powers to fulfill its enumerated responsibilities.[35]

Southern state supreme court justices enunciated this principle of limited but purposeful government as a matter of constitutional doctrine during the war. In Jeffers v. Fair,[36] the Georgia high court held in 1862 that the Necessary and Proper clause “expresses a grant of power—of power commensurate with the object—of power over the populations of the several States, entering into and becoming component parts of the Confederate States of America.” Contrary to a states’ rights oriented theory of government, Associate Justice Charles Jones Jenkins, who had enthusiastically supported Georgia’s secession from the Union, held that constitutional provisions precluded interference by the states with the national exercise of power: “If the true construction of the Constitution be, that in deference to State sovereignty the Confederate Government must depend upon the separate, unconcerted action of the several States for the exercise of powers granted to it in general comprehensive terms, it is but the shadow of a government, the experiment of Confederate Republics must inevitably fail, and the sooner it is abandoned the better.”[37] The Georgia court’s decision was followed in Alabama the following January, in the jointly-decided case of Ex Parte Hill, In Re Armistead v. Confederate States & Ex Parte Dudley.[38]

Federalism

The Confederate framers’ preference for restoring the American federal system was evident in their Constitution’s Preamble where, unlike the U.S. Constitution, they pronounced their intention to create a permanent and federal government.[39] Their objective was to stop the growing power of the national government and to restore the mid-century concept of dual federalism, that doctrine in which the Constitution is understood as a “compact” among states, with each retaining its sovereignty and delegating to the national government only those specific enumerated powers necessary to fulfill national responsibilities and purposes.[40]

This concept of sovereignty was explained in wartime cases as a matter of Confederate constitutional doctrine. Sovereignty, often understood in the American historical context as the totality of political power, is typically delegated or granted by the people to a state or national government and in part or in total. In the American model of federalism, sovereignty is divided so that state and national governments are each vested with power appropriate to their respective duties and responsibilities. Like the U.S. Constitution, in the Confederate Constitution sovereignty emanated from the people. The first phrase of the Preamble, “We the people of the Confederate States,” identified the people of the entire nation, rather than the states, as the source of sovereignty in the Confederacy and as the creators of the nation and its beneficiaries. In Ex Parte Abraham Mayer, decided in 1864, Texas Associate Justice Reuben A. Reeves reinforced this principle, holding that state and Confederate governments were created by the people and “founded on their authority,” contrary to the view of some historians who have argued that sovereignty in the Confederacy emanated from the states.[41]

The second phrase of the Preamble (“each State acting in its sovereign and independent character”) has often been interpreted by historians as a strong statement of states’ rights ideology. However, its placement in the Preamble likely reflects the reality of the state as a unit of political organization and activity within the federal system, with the states, as a political unit, necessary for the transfer of sovereignty from the people to the national government as well as for ratification or adoption of the Confederate Constitution. This was echoed in the framers’ reference to themselves as “the Deputies of the Sovereign and Independent States of South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana,” where they described their role as representatives of their respective states, post-secession and prior to their states’ ratification of the Confederate Constitution. To underscore the permanence of their nation, Confederate framers invoked “the favor of Almighty God” upon their new republic, a feature entirely absent from the U.S. Constitution.[42]

Divided sovereignty in Confederate federalism was explained in 1862, in North Carolina, where Chief Justice Richmond Mumford Pearson, viewed by historians as obstructionist to the Richmond government, declared that the Confederate government was “distinctive,” that sovereignty had not been vested by the people solely with the state, and that philosophical principles about divided sovereignty had been given specific form in the Constitution when states that had seceded “were compelled to give up a portion of their former respective sovereignties, and to invest the newly created government with them.”[43] Two years later, the court affirmed its decision in the case of Gatlin v. Walton.[44]

Three months after the promulgation of the first conscription act in 1862, a Texas case served as the occasion for explaining the Confederate doctrine of federalism and formally rejecting a states’ rights-oriented understanding of the southern constitution. Texan F. H. Coupland argued that Confederate conscription was unconstitutional since the states could assert a greater claim to call up its citizens for military service.[45] He based his claim on the idea that political power (sovereignty) was retained by the states under the Confederate charter, that the Confederacy was a loose confederation of sovereign states, and Richmond’s military draft interfered with a state’s concurrent power to raise military forces.[46]

In Ex Parte Coupland, the Texas high court rejected the state’s attempt to claim a concurrent military equal to that of the Confederate government and held that states’ rights was not “the theory of our government, when properly understood.”[47] In his opinion, Associate Justice George F. Moore vigorously asserted the federal nature of the Confederate nation, holding that the Confederate government, especially Congress, was more than the agent of the states. Confederate framers had made explicit the source of sovereignty, articulating that national legislative power was delegated to Congress in the southern charter rather than having been granted, as specified in the U.S. Constitution. This language required Congress to act as representative of the people; the delegation of sovereignty was temporary and held in trust. In a similar case, Jeffers v. Fair, the court in Georgia held that Confederate conscription was constitutional because it facilitated the express grant of war-making authority in Article I, Section 8, which had been conferred on the Confederate Congress as “agents of the people [emphasis added]” and…”supposed to act under their [the people’s] directions.”[48] Coupland was the first in a series of at least sixteen conscription-related cases from 1862 to 1865 in which the state supreme courts of Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, Texas, and Virginia articulated similar decisions on Confederate federalism and how state and national governments would govern under the Constitution, within their respective areas of responsibility.[49]

Though many state justices had supported secession, the responsibility of rendering judicial review under the new constitution led them to conclusion often contrary to their antebellum political passions. In the 1863 case of Ex Parte Hill, in re Willis, Johnson, and Reynolds v. Confederate States, Alabama Associate Justice George W. Stone, who had supported secession in 1861 and advocated state sovereignty as a justification for disunion, found himself bound by the principles of Confederate federalism. Writing for the court, he held that when the nation and state governments both claimed the same authority, “[t]he jurisdictional area of each government should be kept distinct—restraining the Confederate government within the boundaries of its delegated authority, and not allowing the State governments to trespass on Confederate jurisdiction.”[50] Similar decisions were rendered by wartime courts in Mississippi and Texas.

Though many Confederate framers were former state legislators, the new southern constitution they created also included limitations on state governments, chiefly legislatures, to prevent states from usurping national government powers. This included the Article I, Section 10, clause 3 requirement that states coordinate with the Confederate Congress before imposing duties for the improvement of rivers and harbors. In the exercise of this power, state governments had to demonstrate need and they could not impose duties that violated Confederate treaty obligations. Duties could not be used to raise revenue for other means and surplus revenue generated by such duties had to be paid into the “common [Confederate] treasury.”

Managerial Government

As the American framers discovered with the Article of Confederation, adherence to principles of limited government did not necessarily mean rendering national government powerless. In their new national charter, Confederate framers sought to make national government more effective and responsive by creating a more managerial chief executive who was charged with eliminating government waste, diminishing dissension and conflict, and articulating and leading a more purposeful national government according to designated powers.

Confederate framers sought to raise the Chief Executive above the corrupting influence of partisan politics by creating a single six-year term of office in Article II, Section 1, believing “that they were lifting the president above party politics and freeing him to pursue the national interest.”[51] In 1861, Robert Hardy Smith lamented to his constituents that the U.S. President “’had come to be the appointee of a mere self-constituted and irresponsible convention…as a consequence, each four years heralded the advent of a politician thrown upon the surface by accidental causes and reflecting the latest heretical dogma of a section, rather than addressing himself to the good of the whole country.”[52] The single six-year term was widely lauded, with Harper’s Weekly noting that the single six-year term and ineligibility for reelection “will commend themselves to the approval of all who have watched the mischiefs [sic] produced by the too speedy recurrence of elections, and by the maneuvers of acting presidents for reelection…They would gladly be adopted by the people throughout the Union.”[53] J. L. M. Curry noted that “A President ineligible is freed from the temptation of using his official influence to secure reelection. He is the executive of the whole people and not merely the head of a party.”[54]

Freed from the evils of party politics, the president could function as an efficient national manager leading a lean national bureaucracy.[55] To further this goal, in Article I, section 7, clause 2, the president received the line item veto for arresting “legislative abuses” and to facilitate efficient legislative fiscal processes, undertaken in consultation with the president. Superior to the simple veto in the U.S. Constitution, it returned to Congress identified sections of legislation and subsequently required two-thirds approval. Even if unused, the line-item veto could be wielded as an effective tool, putting Congress on notice regarding special interest legislation and requiring legislators to cooperate with the President.[56]

Moreover, the president, as a representative of the entire nation, was empowered to initiate appropriation bills under Article I, Section 1, clause 9. These could be passed in Congress with a simple majority, unlike the two-thirds vote required for congressionally initiated bills which were assumed tainted by politics and special interests. The framers reasoned that the president, unlike congressmen, responded to a national constituency and therefore was best able to initiate appropriations in the national interest.[57] Alabama Congressman Robert Hardy Smith believed these restrictions necessary, since “the chief Executive as the head of the country and his cabinet should understand the pecuniary needs of the Confederacy, and should be answerable for an economical administration of public affairs.”[58]

Managerial efficiency included making the president more independent by empowering him with unequivocal constitutional removal powers under Article II, Section 2, clause 3 for dismissing Cabinet members and diplomats. He was also provided with removal power for other civil officers when they were no longer necessary or in cases of “dishonesty, incapacity, inefficiency, misconduct, or neglect of duty,” though in these cases, he was required to inform the Senate and provide his reasons. Representative of a “presidential system” of government, this innovation provided the Confederate president with the freedom to direct the affairs of the nation without having to contend with partisanship or the influence of special interests.[59] Strengthening the chief executive was designed “to keep the body politic in a healthy condition.”[60]

Executive-legislative collaboration was also highly valued and Confederate framers demonstrated a willingness to institutionalize greater communication and cooperation between the two branches than that found in the U.S. Constitution. In Article I, Section 6, clause 2 of the provisional constitution, framers provided for Cabinet representation in congressional debate on matters related to their portfolios, providing what Robert Hardy Smith described as “intercourse between the two departments [branches] which was essential to the wise and healthy action of each.”[61] Georgia Congressman J.L.M. Curry remembered that “the restricted privilege worked well while it lasted, and the occasional appearance of cabinet officers on the floor of Congress and participation in debates worked beneficially and showed the importance of enlarging the privilege.”[62] Moreover, in Article 2, Section 2, clause 4, the President was prevented from ignoring Senate objections regarding political appointees and he was prohibited from granting a recess appointment to any person previously rejected by the Senate for that appointment.

Slavery and the Southern Constitution

While both the antebellum U.S. Constitution and the Confederate Constitution afforded protections for slavery, the Confederate charter referred to the institution directly, using the words, “slavery,” and “slaves” throughout, while its U.S. counterpart included no such specific usage. Under Article 1 Section 9 of the U.S. Constitution, the international slave trade was preserved for twenty years following its ratification in 1787. Confederate framers, however, banned the African slave trade completely under Article 1, Section 9, clause 1 of their charter, adding in clause 2 congressional power to prohibit the “introduction of slaves” from states in the Union. This provision, with its threat to cut off the lucrative sale of slaves from the upper South to the cotton states, was intended to secure support from the states of the upper South and to incentivize secession of states in the upper South by ensuring that there would be no new African slave trade to compete with their interest in the interstate slave trade.

The three-fifths clause from the U.S. Constitution, used for determining the apportionment of congressional representatives, was retained in Article I, Section 1, clause 3. Key protections for the institution of slavery were also incorporated into Article IV of the national charter. First, in response to antebellum experience with personal liberty laws, the framers included a specific guarantee to slave owners of the right of transit with their slaves under Section 2, clause 1. Second, the provision for the return of fugitive slaves was retained from the U.S. Constitution in Section 2, clause 3. Third, contrary to the Dred Scott decision,[63] southern framers banned any prohibition against slavery in the territories under Section 3, clause 3.

During the war, two developments raised compelling constitutional issues about the status of slavery. The first was the statutory impressment of slaves as military laborers, following the passage of the Impressment Act of March 26, 1863.[64] Slave owners naturally took exception to this practice by the Confederate government. Although the constitutionality of the national government’s impressment power, especially the Confederate government’s exercise of its eminent domain, was generally affirmed in state supreme courts, a continuing source of dispute in most jurisdictions for the reminder of the war was the implementation of the statute by military authorities and the provision of just compensation.[65]

Claims for just compensation were mediated under the authority of the Secretary of War, including a special board charged with assessing the claims of owners of impressed slaves, as well as in the courts. The adjudication of claims proved to be a necessity due to the complex nature of the legislation and the resulting technical questions about how it might be implemented. Several technical questions were addressed in detailed and insightful opinions authored by the Confederate Attorneys General.[66] These opinions reveal the application of many of the same principles evident in state supreme court decisions enunciating Confederate constitutionalism.[67] In November of 1863, Confederate Attorney General Wade Keyes took up the question of whether the government could impress for temporary use and, if so, what liability ensued for impressed slaves who became sick during government service and died. In a thorough and insightful opinion, Keyes invoked the principle of limited government and noted that while the Confederate Constitution empowered the national government to seize private property, it did so with prescribed limitations. The seizure of private property had to be undertaken for public use. Moreover, the military was subject to two key limitations: it could impress only once an act of Congress had extended this exercise to its officers and the national government was to be liable for all losses under Confederate legislation rather than under the law of the state in which the impressment had been made. This latter guideline, underscoring the need for national standards of valuation, was promulgated in the Impressment Act of March 26, 1863. In recognition of the national government sphere of power and the need for greater managerial efficiency, the change, according to Keyes, imposed a general uniform standard across the southern states and made unnecessary the need to apply differing standards of compensation under the laws of the various states.[68] In 1864, the application of just compensation was taken up several times by the new Attorney General, George Davis, who addressed compensation to owners who hired out their slaves and whether a Georgian Slave Claim Board charged with mediating claims for losses of impressed slaves was authorized to consider the fluctuation of Confederate currency and the awarding of value in interest when determining compensation.[69]

A second development, the enlistment of black troops, raised an intriguing constitutional issue about the citizenship status of freedmen who served as combat troops for the Confederacy and their place in the southern nation. By 1864, three difficult years of America’s first modern war led Confederate political leaders to revise their views about African Americans serving as soldiers for the struggling southern nation. Awarding freedom to African-Americans who defended the Confederacy was a radical measure, first raised in 1863, supported by a number of prominent southerners, the subject of legislative debate in 1864, and eventually the subject of legislation passed in the Confederate Congress on March 13, 1865.[70] In his November 7, 1864 address to the Confederate Congress, President Jefferson Davis supported the proposed legislation to arm slaves, arguing that even those who had served the Confederate war effort as laborers were more than property, and declaring that each slave “bears another relation to the State—that of a person.”[71] Davis’ statement was significant for it acknowledged the personhood of African-Americans (something denied in the Dred Scott decision), their capability to perform the duties of citizens, and their right to assume citizenship rights within the Confederacy as a result. In his 1857 opinion in Dred Scott v. Sandford [sic], Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney held that no African-American possessed standing to sue in a federal court because they could not be considered a U.S. citizen, even if freed.[72] Interestingly, in reaching its option, the Court relied on an 1855 New Hampshire law which denied an African-American the right to serve in the state militia, a duty of military service which the high court regarded as “one of the highest duties of the citizen.” The court went on to note that, in 1855, an African-American in New Hampshire was not, “by the institutions and laws of the State, numbered among its people. He forms no part of the sovereignty of the State, and is not therefore called on to uphold and defend it.”[73] By 1864, though, the exigencies of war had pushed the President of the Confederacy to articulate a radical departure from these U.S. antebellum constitutional opinions, a shift that could have raised interesting and significant constitutional questions about the status of African Americans who fought for the southern nation. During the six months remaining in the Confederacy’s existence, however, no constitutional questions about the place in southern society of African American Confederate soldiers seem to have been litigated and reported.

The plan that emerged by 1865 did not include a general and immediate emancipation of all slaves. Rather, emancipation was a reward for faithful military service. Limited Confederate emancipation was likely shaped by the limitations prominent in Confederate constitutionalism.[74] Under Article IV, Section 2, clause 1, the Confederate Congress was barred from impairing the right of property in slaves, effectively denying any opportunity to promulgate sweeping emancipation legislation, even if such a legislative objective would have engendered the support of legislators to be passed. Moreover, the Article IV, Section 3, clause 4 guarantee to a republican form of government and the language of Article VI, Section 6, reserving to the states those powers not delegated to the Confederate government, both operated as a bar on Confederate government power and left to the states to decide whether slavery, as an institution, would be protected or ended.[75] The Confederate constitutional order, which incorporated a dedicated commitment to limited government and dual federalism, may not have been quite prepared for such a radical step as general, universal emancipation in the Confederacy.

With its roots in the U.S. Constitution of 1787 and its reforms originating in the political conflicts of the 19th century, the Confederate Constitution represented a distinctive chapter in American constitutionalism. Antebellum political antipathy towards corrupt political practices prompted southern framers to re-examine the American constitutional framework and towards a constitutional conservatism, especially a return to principles of limited but representative government. Yet, political dissent and a drive for greater efficiency also fostered innovation and the new nation’s charter was distinctive, incorporating new features and forms, clarifying ambiguities regarding federalism and the constitutional balance of power in the Confederacy, realigning the separation of powers found in the Constitution of 1787 in favor of a more restrictive legislature and a more powerful managerial presidency, and developing new management configurations, expectations, and responsibilities.

War-related issues proved to be the impetus for much of the judicial review of the document and the only authoritative exposition of the document was rendered during war. Due to political developments, this task of enunciating the Confederate Constitution fell principally and, due to the stature of the state courts and the volume of wartime cases, most authoritatively to state supreme courts. Many of the justices rendering decisions in these courts had been ardent secessionists in 1860-1861 and almost all were associated deeply with lifelong political affiliations within their respective states. Despite these strong orientations towards their states, the justices rendered judicial review with deliberative review and circumspection and, through judicial review, they rejected states’ rights, a theory which had justified secession, as the nation’s configurative constitutional theory. With remarkable consistency, state courts across the Confederacy rendered similar decisions and, in so doing, functioned largely as a de-facto national supreme court. Unfortunately, many of their Confederate constitutional decisions are today unknown or ignored. While decisions from some jurisdictions are available currently in state reporters, decisions from other jurisdictions went unreported or were de-published after the war, were reported only in newspapers before being destroyed, or were dispersed to various regional and state repositories for storage and may not always be easy to locate.[76]

A Confederate constitutional order never existed during peacetime, as it did for the U.S. Constitution of 1787. If it had, a more objective understanding of the southern charter, the regular operation of government it proposed, and a more direct comparison with the U.S. Constitution might be possible. Nonetheless, the permanent Confederate Constitution offers a distinctive view of mid-nineteenth century political thought, southern efforts to reform American constitutionalism, and how southern ideas coalesced and led Confederate framers to develop a constitution they hoped would reform the constitutional and political order they had known while in the Union. It provides, in a sense, an historically important American constitutional moment.

- [1] George Anastaplo, The Amendments to the Constitution: A Commentary (Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press, 1995), 126, 127-31; United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 vols. in 128 parts (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series IV, volume 1, p. 9-10 (hereafter cited as O.R., IV, 1, 9-10).

- [2] William M. Robinson, Jr., “A New Deal in Constitutions,” in The Journal of Southern History, 4, (November 1938): 454.

- [3] The full text of the Permanent Confederate Constitution is available at: http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/csa_csa.asp, accessed August 31, 2020.

- [4] Edward L. White, III, “The Constitution of the Confederate States of America: Innovation or Duplication?” in The Southern Historian 12 (1991):8-9; Donald Lutz, Origins of American Constitutionalism (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1988), 16.

- [5] Albert N. Fitts, “The Confederate Convention: The Constitutional Debate,” Alabama Review 2 (1949):204.

- [6] Robert H. Smith, An Address to the Citizens of Alabama on the Constitution and Laws of the Confederate States of America by the Hon. Robert H. Smith, (Mobile, AL: Mobile Daily Register Print, 1861), 12.

- [7] Montgomery, The Weekly Mail, March 22, 1861.

- [8] The Intelligencer (Atlanta), February 16, 1862.

- [9] New Orleans Daily Picayune, February 25, 1862.

- [10] New York Herald, March 19, 1861.

- [11] Harper's Weekly 5, no. 222 (March 30, 1861):194.

- [12] Add Jefferson Davis quote from inaugural

- [13] James M. Matthews, ed., Statutes at Large of the Provisional Government of the Confederate States of America, from the Institution of the Government, February 8, 1861, to its Termination, February 18, 1862, Inclusive (Richmond, VA: R. M. Smith Printer to Congress, 1864), chap. LXI, 75-87.

- [14] The habeas corpus clause of the Confederate Constitution is found in Article 1, Section 9, clause 3. It provided that “The privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it.” Use of the writ and its effect on civil liberties in the Confederacy is addressed in Mark Neely, Southern Rights: Political Prisoners and the Myth of Confederate Constitutionalism (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1999), 59.

- [15] Kermit Hall, Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States, (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1992), 357-358.

- [16] Donald Nieman, “Republicanism, The Confederate Constitution, and the American Constitutional Tradition,” in Kermit L. Hall and James W. Ely, Jr., eds. An Uncertain Tradition: Constitutionalism and the History of the South (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1989), 201-224, 216.

- [17] Roger D. Hardaway, “The Confederate Constitution: A Legal and Historical Examination,” The Alabama Historical Quarterly 44, nos. 1 & 2 (Spring & Summer 1982):27; Marshal L. DeRosa, The Confederate Constitution of 1861: An Inquiry into American Constitutionalism (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1991), 42.

- [18] Journal of the Congress of the Confederate States of America, 7 vols. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904), 1:909-923; Charles Robert Lee, Jr. in The Confederate Constitutions (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1963), 173.

- [19] Ibid., 119; White, “The Constitution of the Confederate States of America: Innovation or Duplication?” 20.

- [20] J. L. M. Curry, Civil History of the Government of the Confederate States (Richmond, VA: B.F. Johnson Publishing Co., 1901), 11-41, 50; White, “The Constitution of the Confederate States of America: Innovation or Duplication?” 5.

- [21] T. R. R. Cobb, Substance of An Address of T.R.R. Cobb, To His Constituents of Clark County, April 6th, 1861 (Clark County GA: 1861), 4; Curry, Civil History, 83; White, “The Constitution of the Confederate States of America: Innovation or Duplication?” 11.

- [22] Cobb, Substance of An Address 4.

- [23] Each bill was limited to one subject, explicitly stated in the title, see Article I, Section 9, clause 20; White, “The Constitution of the Confederate States of America: Innovation or Duplication?” 14.

- [24] Ibid., 14-15.

- [25] An analysis of the Confederacy’s uneven record on civil liberties during the war is the focus in Mark Neely, Southern Rights: Political Prisoners and the Myth of Confederate Constitutionalism (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1999).

- [26] Ex Parte Hill, In Re Willis, et al. 38 Ala. 429, 454-6 (1863).

- [27] Ex Parte Abraham Mayer, 26 Tex. 715 (1864).

- [28] There were two impressments statutes, the first passed on March 26, 1863, which allowed for the military’s seizure of necessary stores, “An Act to Regulate Impressments,” chapt. X, in James M. Matthews, ed., The Statutes at Large of the Confederate States of America, Passed at the Third Session of the First Congress; 1863. (Richmond, VA: R.M. Smith, 1863), 102-104. This was followed by a second act passed on February 16, 1864 which provided procedures for establishing “fair and just” compensation and an appeals process, see “An Act to amend ‘An act to regulate impressments,’ approved March twenty-sixth, eighteen hundred and sixty-three, and to repeal an act amendatory thereof, approved April twenty-seventh, eighteen hundred and sixty-three,” chapt. XLIII, in The Statutes at Large of the Confederate States of America, Passed at the Fourth Session of the First Congress; 1863-4. (Richmond, VA: R.M. Smith, 1864), 192-193.

- [29] “An Act to Regulate Impressments, March 2, 1863. This was followed by April 30, 1863 and the War Department’s General Orders No. 37 of April 6, 1863. The acts of April 27, 1863 and February 16, 1864 focused on how just compensation was to be determined.

- [30] Cox & Hill v. James F. Cummings 33 Ga. 549 (1863).

- [31] Ibid., 556. Lumpkin looked to the U.S. Supreme Court case of Vanhorne’s Lessee v. Dorrance, 2 U.S. (2 Dall.) 304 (1795) in which Justice Patterson emphasized the importance of establishing fair and just compensation to preserve the rights of the private property owner, “’except in cases of absolute necessity or great public utility.’” 33 Ga. 549, 557.

- [32] Ibid, 631-633.

- [33] 39 Ala. 307 (1864).

- [34] Ibid., 309.

- [35] See the Georgia Supreme Court on this point in Thomas Barber v. William A. Irwin, 34 Ga. 27, 37-38 (1864).

- [36] Jeffers v. Fair, 32 Ga. 347 (1862).

- [37] Ibid., 364-5.

- [38] 38 Ala. 458 (1863).

- [39] Nieman, “Republicanism, the Confederate Constitution, and the American Constitutional Tradition,” 203; Albert N. Fitts, “The Confederate Convention: The Constitutional Debate,” Alabama Review 2 (1949), 189-210; Journal of the Congress of the Confederate States of America, 1:899-909.

- [40] Harry N. Scheiber, “Dual Federalism,” in Kermit L. Hall, et al. eds., The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 236.

- [41] 26 Tex. 715 (1864).

- [42] Journal of the Congress of the Confederate States of America, 1:899; see generally, 1:899-909.

- [43] In Re Bryan, 60 N.C. 1, 10 (1862). This principle was not a dry question of law but a matter of public discussion. The Salisbury Carolina Watchman noted the limitations upon state government, based upon the sovereignty that had been vested in the national government by the people: “The State has delegated to the Confederate Government the sole right to declare war and make peace. While in the Confederacy...the State cannot make peace or negotiate for it. To do this...the State must first recall the rights of sovereignty which she has vested in the Confederate Government.” The Salisbury Carolina Watchman, May 2, 1864.

- [44] 60 N.C. 205 (1864).

- [45] Ex Parte Coupland, 26 Tex. 387 (1862). The first conscription act was passed by the Confederate Congress on April 16, 1862. See James M. Matthews, ed., Statutes at Large, 1 Cong., 1 Sess., 1862 , Chapter XXXI, section 1, 263. This act was entitled “An Act to further provide for the public defence [sic].”

- [46] 26 Tex. 387, 392.

- [47] 26 Tex. 387, 403.

- [48] Ibid., 394.

- [49] Ex Parte Coupland, 26 Tex. 386 (1862); Jeffers v. Fair, 32 Ga. 347 (1862); In Re Bryan, 60 NC 1 (1862); James L. Mims & James D. Burdett v. John K. Wimberly, 33 Ga. 587 (1863); Ex Parte Turman, 26 Tex. 708 (1863); Ex Parte Hill, in re Willis, Johnson, and Reynolds v. Confederate States, 38 Ala. 429 (1863); Ex Parte Stringer, 38 Ala. 457 (1863); Ex Parte Tate, 39 Ala 254 (1864); Ex Parte Lee and Allen, 39 Ala. 457 (1864); Burroughs v. Peyton, 16 Va. 470 (1864); Thomas W. Cobb v. William B. Stallings & B. A. Baldwin v. John West, 34 Ga. 72 (1864); David Simmons v. J.H. Miller, Enrolling Officer, 40 Miss. 19 (1864); Gatlin v. Walton, 60 NC 205 (1864); Daly & Fitzgerald v. Harris, 33 Ga. 38 (1864); Ex Parte William A. Winnard, [unreported Texas decision] (1865); Theodore Parker v. Charles Kaughman, 34 Ga. 136 (1865); and Ex Parte Ainsworth, 26 Tex. 731 (1865).

- [50] 38 Ala. 429, 446, 454 (1863).

- [51] Smith, An Address, 13-14 and Nieman, “Republicanism, the Confederate Constitution, and the American Constitutional Tradition,” 207.

- [52] Smith, An Address, 13.

- [53] Harper's Weekly 5, no. 222 (March 30, 1861), 194; Nieman, “Republicanism, the Confederate Constitution, and the American Constitutional Tradition,” 209.

- [54] Curry, “The Confederate States and Their Constitution” in The Galaxy 17, no.3 (March 1874): 402; Smith, An Address , 13-14; Nieman, “Republicanism, the Confederate Constitution, and the American Constitutional Tradition,” 207.

- [55] Fitts, “The Confederate Convention: The Constitutional Debate,” 194.

- [56] DeRosa, The Confederate Constitution, 84.

- [57] Milledgeville Southern Recorder, February 19, 1861.

- [58] Smith, An Address, 7-8.

- [59] DeRosa, The Confederate Constitution, 81-82.

- [60] Milledgeville Southern Recorder, February 19, 1861.

- [61] Smith, An Address, 9.

- [62] Curry, Civil History, 83.

- [63] Dred Scott v. Sandford, [sic] 60 U.S. 393 (1857)

- [64] Confederate States of America, Journal of Congress, 1st Cong., 3rd Sess., III, 191.

- [65] See Cox & Hill v. James F. Cummings, 33 Ga. 549 (1863) and Alabama and Florida Railroad Co. v. Kenney, 39 Ala. 307 (1864)

- [66] Confederate States of America, and Rembert Wallace Patrick.The Opinions of the Confederate Attorneys General, 1861-1865. Buffalo, N.Y.: Dennis, and Co., 1950, Vol. 9, “Liability of Government for Impressed Slaves,” November 5, 1863, 345-351, Ibid., Vol. 10, “Liability of Government for Impressed Slaves,” April 29, 1864, 437-438 and “Liability of Government for Impressed Slaves,” July 11, 1864, 459-464.

- [67] See Tyson v. Rogers, 33 Ga. 473 (1863), in which the court held that in the absence of any legislative enactment, military necessity was an inadequate reason for military authorities to impress slaves as military laborers in military hospitals.

- [68] Opinions of the Confederate Attorneys General, “Liability of Government for Impressed Slaves,” Vol. 9, November 5, 1863, 345-351, 349.

- [69] Ibid., Vol. 10, “Liability of Government for Impressed Slaves,” April 29, 1864, 437-438 and “Liability of Government for Impressed Slaves,” July 11, 1864, 459-464.

- [70] Frank Vandiver, ed., “Proceedings of the Second Confederate Congress,” Southern Historical Society Papers (new series), vols. 51-52 (Richmond, VA: Virginia Historical Society, 1958-1959), vol. 52, 470. The legislation would have impressed slaves, provided just compensation to the owner, under law, and then put the Confederate States government in the position to free impressed slaves as a reward for faithful military service. Freedom under this legislation was not immediate emancipation nor applicable to the entire slave population of the South. Emancipation followed only after military service under the national legislation. The legislation set up an eventual clash with the states since under the Confederate Constitution, a state was the only governmental entity authorized to end slavery in their state. DeRosa, The Confederate Constitution, 66-68.

- [71] James D. Richardson, A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Confederacy, 2 vols. (Nashville: United States Publishing Company, 1906), 1:493-494.

- [72] Taney’s holding provided that “neither the class of persons who had been imported as slaves nor their descendants, whether they had become free or not, were then acknowledged as a part of the people, nor intended to be included in the general words used in that memorable instrument” [the Declaration of Independence)] and “they have never been regarded as a part of the people or citizens of the State, nor supposed to possess any political rights which the dominant race might not withhold or grant at their pleasure.” See Dred Scott v. Sandford [sic], 60 U.S. 393, 407, 412 (1857).

- [73] 60 U.S. 393, 415,

- [74] DeRosa, The Confederate Constitution, 57-78.

- [75] Ibid., 68-69.

- [76] See William Robinson, Justice in Grey, and A History of the Judicial System of the Confederate States of America, Russell and Russell 1968 ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1941), 635-9. In Texas, a synopsis of wartime cases was produced by Charles Robards, former clerk of the Texas Supreme Court. His short volume includes eighteen wartime habeas corpus cases that were never reported in the state’s official court reporters. Charles L. Robards, Synopses of the Decisions of the Supreme Court of the State of Texas (Austin, TX: Brown and Foster, 1865). Some vestiges of the Confederate constitutional order have survived, chiefly the innovation of a Department of Justice and the periodic attempts to revise Article 2 of the U.S. Constitution to include a single six-year term for the U.S. president.

If you can read only one book:

Lee, Charles Robert, Jr. Federalism in the Southern Confederacy. Washington, D.C.: Public Affairs Press, 1966.

Books:

Amlund, Curtis Arthur. Federalism in the Southern Confederacy. Washington, D.C.: Public Affairs Press, 1966.

Anastaplo, George. “The Confederate Constitution of 1861,” in George Anastaplo, The Amendments to the Constitution: A Commentary. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press, 1995.

Currie, David P. “Through the Looking-Glass: The Confederate Constitution in Congress,’ 1861-1865,” in Virginia Law Review (2004): 1257-399.

Curry, J. L. M. Civil History of the Government of the Confederate States. Richmond, VA: B. F. Johnson Publishing Co., 1901.

DeRosa, Marshal L. The Confederate Constitution of 1861: An Inquiry into American Constitutionalism. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1991.

Fehrenbacher, Don E. Constitutions and Constitutionalism in the Slave-Holding South. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1989.

Fitts, Albert N. “The Confederate Convention: The Constitutional Debate,” in Alabama Review 2 (1949): 189-210.

Hamilton, J.G. DeRoulhac. “The State Courts and the Confederate Constitution,” in The Journal of Southern History 4 (November 1938): 425-48.

Hardaway, Roger D. “The Confederate Constitution: A Legal and Historical Examinatio,” in The Alabama Historical Quarterly 44, nos. 1 & 2 (Spring & Summer 1982):18-31.

LaCroix, Alison. “Continuity in Secession: The Case of the Confederate Constitution," in University of Chicago Public Law & Legal Theory Working Paper No. 512, 2015.

Matthews, ed., James M. Statutes at Large of the Provisional Government of the Confederate States of America, from the Institution of the Government, February 8, 1861, to its Termination, February 18, 1862, Inclusive. Richmond, VA: R. M. Smith Printer to Congress, 1864.

Mitchell, Memory F. Legal Aspects of Conscription and Exemption in North Carolina, 1861-1865. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1965.

Moore, Albert Burton. Conscription and Conflict in the Confederacy. New York: Hillary House Publishers Ltd., 1963.

Nieman, Donald. “Republicanism, The Confederate Constitution, and the American Constitutional Tradition,” in Kermit L. Hall and James W. Ely, Jr., eds., An Uncertain Tradition: Constitutionalism and the History of the South. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1989, 201-24.

Powell, Michael A. “Confederate Federalism: A View from the Governors,” Ph.D. diss., University of Maryland, College Park, 2004,

OCLC (70708469).

Robinson, Jr., William M. “A New Deal in Constitutions,” in The Journal of Southern History 4 (November 1938), 449-61.

————. Justice in Grey, A History of the Judicial System of the Confederate States of America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1941.

Smith, Robert Hardy. An Address to the Citizens of Alabama on the Constitution and Laws of the Confederate States of America by the Hon. Robert H. Smith. Mobile, AL: Mobile Daily Register Print, 1861.

Stelluto, Donald L. “‘a light which reveals its true meaning’: State Supreme Courts and the Confederate Constitution” Ph.D. diss., University of Maryland, College Park, 2004, OCLC (70846708).

White, III, Edward L. “The Constitution of the Confederate States of America: Innovation or Duplication?,” in The Southern Historian 12 (1991):5-28.

No Author. Journal of the Congress of the Confederate States of America, 7 vols. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

The Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History, and Diplomacy (see Confederate States of America: Documents for the Confederate official document like the Provisional and Permanent Confederate Constitutions, Jefferson Davis’ annual Message to Congress, and other government-related documents.

Journal of the Congress of the Confederate States of America, 7 vols. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904) is the official record of the debates and legislation of the Confederate Congress.

Statutes at Large of the Provisional Government of the Confederate States of America, from the Institution of the Government, February 8, 1861, to its Termination, February 18, 1862, Inclusive. Richmond, VA: R. M. Smith Printer to Congress, 1864.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.