The Helena Campaign

by G. David Schieffler

The battle of Helena occurred on July 4, 1863, a day when Union armies scored key victories in three different locations. One of those was at Gettysburg, where on July 1-3 federal forces defeated Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, which retreated on July 4. On that same day, 1,000 miles to the southwest, Union forces under Ulysses S. Grant forced the surrender of Vicksburg, the most important rebel stronghold on the Mississippi River. Among the smallest military engagements of the day occurred at Helena, 200 miles upriver from Vicksburg, but while overshadowed and mostly forgotten, Helena was by no means insignificant. The Union occupation of Helena was a constant threat to the Confederacy’s control of the Mississippi River and the Arkansas interior. The Helena campaign was initiated to eliminate that threat. In the end, the July 4 attack was too little and too late to save Vicksburg. Still, the battle of Helena proved to be among the most significant engagements of the Civil War in the Trans-Mississippi. Over 1,800 men were killed, wounded, or captured in the campaign (over 15% of those involved), and its outcome ensured federal control of the Mississippi River. General Theophilus Hunter Holmes led the Confederate army that attacked Helena, while Major General Benjamin Mayberry Prentiss commanded the 4,100-man federal garrison at Helena. Prentiss took advantage of commanding terrain to construct strong fortifications, while Holmes struggled with difficult terrain and weather to bring his forces to confront Prentiss. A combination of natural and built obstacles, as well as errors made by the Confederate commander, combined to defeat the Confederate attackers. After several hours of intense combat, the Confederates were forced to retreat. The Helena campaign was a disaster for the Confederates, and nature molded the actions and intentions of both armies and played a fundamental part in a campaign that ensured federal control of the Mississippi River, preserved the Union foothold in eastern Arkansas, and paved the way for federal control of Little Rock only two months later.

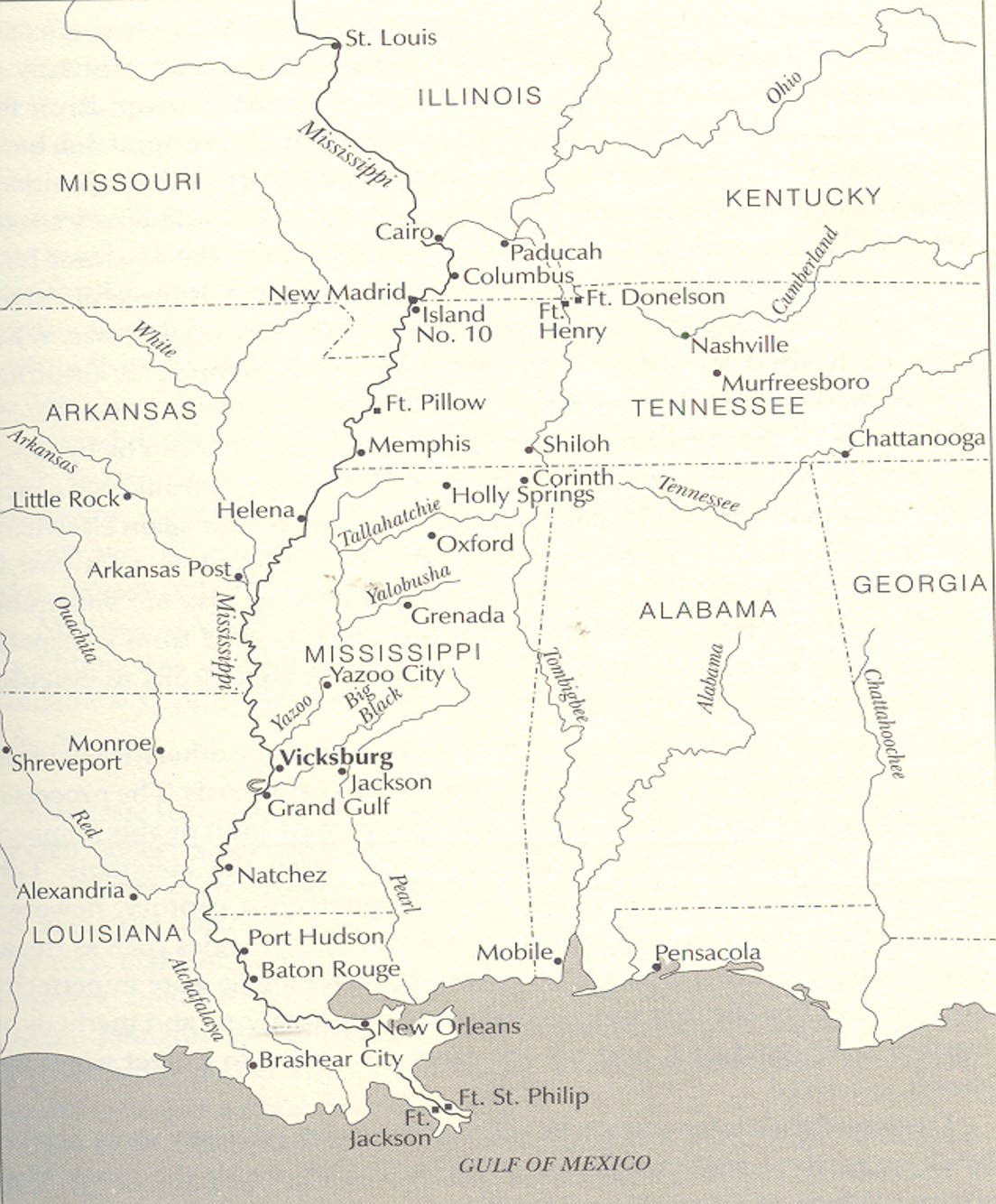

Map Showing the Location of Helena on the Mississippi River

Map Courtesy of: William L. Shea and Terrence J. Winschel, Vicksburg is the Key: The Struggle for the Mississippi River (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003), p. 3.

In December 1887, Union veteran W. A. Jenkins delivered a speech to a gathering in Illinois. Jenkins’s topic was the battle of Helena, a July 1863 engagement in which more than 7,000 Confederates attacked and were repulsed by 4,100 Federals entrenched at Helena, Arkansas, on the Mississippi River. “Had the Battle of Helena occurred at almost any other period during the war,” Jenkins proclaimed, “it would have been heralded far and wide all over the land, for what it really was, —a splendid victory.” [1]

Although Jenkins’s participation in the Union victory at Helena certainly contributed to his lofty opinion of the battle, his observation nevertheless highlights an important point about the engagement’s place in history. The battle of Helena occurred on July 4, 1863, a day when Union armies scored key victories in three different locations. One of those was at Gettysburg, where on July 1-3 federal forces defeated Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, which retreated on July 4. On that same day, 1,000 miles to the southwest, Union forces under Ulysses S. Grant forced the surrender of Vicksburg, the most important rebel stronghold on the Mississippi River. Among the smallest military engagements of the day occurred at Helena, 200 miles upriver from Vicksburg, but while overshadowed and mostly forgotten, Helena was by no means insignificant. The rebel attack on the Union garrison was conceived at the highest level of the Confederate command. It was intended as an important strategic move to relieve pressure on the collapsing Confederate garrison at Vicksburg and to secure an important Confederate position on the Mississippi River in case of Vicksburg’s surrender. The Federals had gained control of Helena in the summer of 1862, and for the next year, they used it as an important staging ground and supply depot for military operations on the Mississippi, particularly those aimed at Vicksburg. The Union occupation of Helena was a constant threat to the Confederacy’s control of the Mississippi River and the Arkansas interior. The Helena campaign was initiated to eliminate that threat. In the end, the July 4 attack was too little and too late to save Vicksburg, which capitulated on the same morning. Still, the battle of Helena proved to be among the most significant engagements of the Civil War in the Trans-Mississippi. Over 1,800 men were killed, wounded, or captured in the campaign (over 15% of those involved), and its outcome ensured federal control of the Mississippi River. It also preserved the Union foothold in eastern Arkansas, which, in turn, allowed the Federals to capture Little Rock only two months later. [2]

The Helena campaign deserves consideration for all of these reasons. It also merits scholarly attention because it lucidly illustrates a number of ways in which the natural environment shaped the course and conduct of the Civil War. In recent years, scholars have shown that nature played an important, sometimes decisive, role in the conflict. [3] The Helena campaign offers yet another example of that impact. In the summer of 1863, the Confederates believed if they moved against Helena with “celerity and secrecy,” they would easily capture the post. [4] However, the natural environment of east Arkansas—and the Union army’s strategic use of that environment—prevented the Confederates from achieving those ends. Harsh environmental conditions during the rebel approach to Helena in tandem with the federal garrison’s ability to leverage the landscape as a key ally during the battle led to Confederate defeat and, by extension, solidified Union control of the Mississippi River and Arkansas. [5]

Union and Confederate officials appreciated the significance of Helena’s topography in the war’s opening months. Crowley’s Ridge, an upland reaching heights up to 250 feet above the surrounding delta land, originates just north and west of Helena and extends north for 150 miles to southern Missouri. As the only high ground on the Mississippi’s western bank between Missouri and the Gulf of Mexico, the ridge represented a strategic position for anyone trying to control traffic on the river. The Confederates maintained ostensible control of Helena during the war’s first year, though, like other rebel positions in the Mississippi Valley, their fortunes changed in 1862. Following its victory at the Battle of Pea Ridge, General Samuel Ryan Curtis’s Union Army of the Southwest began a long march east that would eventually end at the Mississippi River. After three months and 500 miles of marching, Curtis’s army reached and occupied an undefended Helena in July 1862. [6]

For the next year, Helena served as a permanent Union enclave and a crucial staging ground and supply depot for operations in the Mississippi Valley. Although the troops stationed there enjoyed the benefits of a river-based supply line, few found comfort in the low-lying, oft-flooded river town, which they nicknamed “Hell-in-Arkansas.” [7] Nevertheless, the Union occupation of the town posed a continual threat to the Confederacy’s control of the Mississippi River and the Arkansas interior, and throughout 1862 and 1863, the Confederates contemplated removing that threat. At one time or another, recommendations for attacking Helena were made by such high-ranking Confederates as Inspector General Samuel Cooper, Secretary of War George Wythe Randolph, Secretary of War James Alexander Seddon, Robert E. Lee, and Jefferson Davis. Ultimately, however, responsibility for capturing the town fell to General Theophilus Hunter Holmes, commander of the Confederate District of Arkansas. In the summer of 1863 Holmes received word that “all Federal troops that [could] be spared [were] being sent to re-enforce Grant” at Vicksburg, thereby leaving Helena’s garrison “very weak.” This promising intelligence prompted Holmes to seek permission to attack the town, and in June 1863, Lieutenant General Edmund Kirby Smith, commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department, granted it. [8]

Holmes, who would personally lead the attack, called for two Confederate columns to begin converging on Helena on June 21. He ordered Sterling Price’s 3,095-man infantry division and Brigadier General John Sappington Marmaduke’s 1,750-man cavalry division to move south from Jacksonport, Arkansas, while Brigadier General James Fleming Fagan’s 1,339 infantrymen traveled east from Little Rock. Holmes told these units to rendezvous with Brigadier General Lucius Marshall “Marsh” Walker’s 1,462-man cavalry division, which had already been operating near Helena. [9]

What happened next became a small-scale version of Major General Ambrose Everett Burnside’s infamous “Mud March” in Virginia the previous winter. On June 22, Price and Marmaduke began their march south, and two days later, heavy rains transformed the roads on their route to mud and the creeks in their path to torrents. The rain fell incessantly for four days, and three different streams—now all overflowing their banks—mired the Confederate advance. One officer summed up their predicament on the banks of the first river: “It is utterly impossible to get my train across…. The mud is so deep . . . that mules cannot stand up.” Price dispatched engineers ahead to construct bridges across the other two streams, but floods swept away the bridges before the infantry could cross. Predictably, Fagan’s brigade faced similar difficulties on its journey eastward. One of his soldiers later wrote, “It is useless to tell . . . anything of the hardships of our marches through the . . . swamps, no one but an actual participant, can picture anything like the reality. It was mud & water all the time from ‘knee’ deep up to the arm pits. It would not be surprising if the number of sick from exposure on this trip will equal that of the killed and wounded in the fight ….” On July 1, a frustrated Holmes, who accompanied Fagan’s column, wrote to Price: “I deeply regret the difficulties that cause the delay in your march. I have used every precaution to prevent a knowledge of our approach reaching the enemy, and have what I believe to be certain information that I had succeeded up to the night before last. I fear these terrible delays will thwart all my efforts.” As it turned out, Holmes’s fears were justified—nature had blown the Confederates’ cover. [10]

Meanwhile, Major General Benjamin Mayberry Prentiss (of Shiloh’s “Hornet’s Nest” fame) commanded the 4,100-man Union garrison at Helena, and he set out to use the surrounding landscape to his defensive advantage. Previous federal garrisons had already established suitable defenses prior to Prentiss’s arrival, but the general supervised their improvement. An earthen redoubt called Fort Curtis, which was equipped with several large siege guns, protected the western edge of town. [11] Several hundred yards to the west of Fort Curtis stood four prominent hills—the foothills of Crowley’s Ridge—which, according to one soldier, were “divided by numerous deep and narrow gorges, where in many places a man could only walk with difficulty.” Under Prentiss’s supervision, Union troops and former slaves leveraged the natural terrain to their advantage by building batteries on the peaks of the hills, each armed with two guns and protected by earthen walls, sandbags, and a series of connecting rifle pits. The Federals labeled the batteries, from north to south, A, B, C, and D. Cavalry, rifle pits, and additional batteries protected the flanks of this western line of defense. To further fortify the garrison, defensive-minded Federals felled trees in the gorges and roads leading into town. Helena’s troops loathed the hard work, but they continuously boasted about their garrison’s natural and man-made defenses. One soldier wrote, “This is a very well fortified place and . . . the country in the rear of town is a continuation of hills which are the most natural fortifications I have ever seen. On many of them, we have Batteries planted and rifle pits dug so it seems as though every avenue into the town is so commanded as to make it impossible for a rebel army to get in here….” [12]

The Federals also utilized their natural riverside location to bolster the defenses on the east side of town. When Admiral David Dixon Porter heard rumors in mid-June that the Confederates were advancing on Helena, he sent three gunboats there. Only one, the USS Tyler, would be present during the July 4 battle, though by most counts, it played an important role in the engagement. [13]

Rumors of an impending Confederate attack circulated in Helena throughout the spring of 1863. [14] Prentiss, however, was not convinced that an attack was imminent until June 25—just as swollen creeks and muddy roads impeded the Confederate approach. For an entire week before the battle, he issued orders that the “entire garrison should be up and under arms at 2.30 o’clock each morning.” On July 1, Prentiss learned that Confederate forces had congregated about 15 miles from Helena. To his soldiers’ dismay, he cancelled the garrison’s scheduled Fourth of July celebration as a precautionary measure. [15]

Two days later, the Confederates finally converged on the outskirts of town. After trudging through mud and fording flooded streams, the tired and dispirited rebels had at last reached their objective. The natural environment, though, had prevented them from doing so according to schedule. One rebel soldier later recognized the costs of the delays: “There had been heavy rains which made the roads impassable and corduroy roads had to be constructed the entire way; this with the building of bridges across all swollen streams delayed the movement so much that the enemy learned of our coming and had ample time to prepare for our reception….” Gen. Holmes concurred. “Price was unavoidably four days behind time in consequence of high water and bad roads,” he lamented, “which gave the enemy ample time to prepare for me.” Nevertheless, the Confederate generals moved forward with their plans. On July 3, Holmes briefed his subordinates on Helena’s defenses, which were stouter than he had originally believed them to be. “[T]he place was very much more difficult of access,” he declared, “and the fortifications very much stronger, than I had supposed before undertaking the expedition, the features of the country being peculiarly adapted to defense, and all that the art of engineering could do having been brought to bear to strengthen it.” [16]

Faulty intelligence, poor reconnaissance, and the Federals’ strategic use of the environment had placed the Confederates in a precarious position before the first shots were fired. Still, Holmes stayed committed to the attack. He called for a three-pronged assault against heavily fortified, entrenched federal positions on high ground. Marmaduke’s cavalry would attack battery A on the north end of town, Price’s division would capture battery C in the center, and Fagan would assault battery D in the south. Walker’s cavalry, which had been picketing Helena’s approaches for several weeks, would protect Marmaduke’s left flank and, after battery A was captured, “enter the town and act against the enemy as circumstances may justify.” [17]

As the Confederates moved into position the night before the battle, they unexpectedly found their paths blocked by felled timber. Below battery D, Fagan observed that the road was “completely filled with felled timber, the largest forest growth intermingling and overlapping its whole length, while on either side precipitous and impassable ravines were found running up even to the very intrenchments of the enemy.” Fagan’s predicament was not unique. Federal abatis mired the advance of all three Confederate columns and forced them to abandon their artillery and ammunition trains before the battle had even commenced. By the time they reached their attack positions, most of the Confederates were exhausted from the long night’s march through deep ravines and thick timber. They also lacked artillery support. [18]

In order to achieve coordination, Holmes ordered the Confederate attack to begin on the morning of July 4 at “daylight,” a vague time designation that had disastrous consequences. Price misinterpreted Holmes’s order to mean “sunrise,” so upon reaching the base of the hill below battery C, he halted his men until then. While Price’s men dallied, Fagan and Marmaduke launched their assaults at first light, thus ending any possibility of a synchronized attack. The Confederates’ poor coordination allowed the Federals manning the four batteries and the gunboat Tyler to concentrate their fire on whichever point the Confederates threatened, a luxury that had devastating effects on the Confederate assailants. [19]

As daylight arrived, the Confederates emerged from the brush and attacked the entrenched bluecoats. “[A]mid the leaden rain and iron hail,” they climbed up the hills, which were “so steep the men had to pull themselves up by the bushes.” One Confederate soldier recalled that “the hills and hollows running parallel to [the federal] works . . . compelled us to charge over the hills exposed to a deliberate and murderous fire. Then to make the matter worse the timber had been felled in such a manner as to make it next to impossible to pass over this ground at all.” [20]

After several hours of intense combat, neither Fagan’s infantry nor Marmaduke’s cavalry had reached their objectives, but remarkably, Price’s troops managed to seize battery C. A few minutes later, however, the scene at battery C became chaotic. In the words of Holmes, who entered the captured battery, “Everything was in confusion, regiments and brigades mixed up indiscriminately” as the Confederates struggled to secure their position, advance against the Federals, and shield themselves from the Union bombardment. Adding to the chaos, Holmes then ordered one of Price’s battalion commanders to attack Fort Curtis. The general’s order, which violated the chain of command, had disastrous consequences. The other Confederate officers in the vicinity saw the advance on Fort Curtis and, believing that a general attack had been ordered, instructed their men to charge the fort. The dashing Confederates, who immediately became the target of Fort Curtis, the batteries, the USS Tyler’s guns, and a hail of enfilading rifle fire, were either captured or massacred. Shortly thereafter, Holmes ordered a general retreat. [21]

The Helena campaign was a disaster for the Confederates, due in no small part to their commander’s blunders. And yet, Holmes should not shoulder all the blame. The unpredictable forces of nature, as well the Federals’ strategic use of the natural environment, played a decisive role in the campaign’s outcome. Those who fought in the battle understood this fact. Reflecting on the battle the following month, one Union soldier believed “it was not alone the bravery of our men that saved Helena. It was the defences & the manner in which the troops were disposed in readiness for any emergency & the untiring vigilance which prevented the enemy from gaining a foothold.” [22] Tellingly, a defeated Confederate offered similar analysis: “The facts can be summed up in very few words. We were badly whiped—not from any want of bravery on the part of men or officers, but the natural position together with the “fortifications” around the place would have defied almost twice our numbers.” [23]

The Helena campaign cannot be understood without some consideration of the ways in which soldiers manipulated, and were shaped by, their natural environment. Historians have proven that nature played an important, sometimes paramount, part in the Civil War, and the Helena campaign offers a vivid illustration of that fact. And yet, the natural environment alone did not determine the outcome at Helena. Other variables, including the decision-making of such individuals as Theophilus Holmes and Benjamin Prentiss, were also consequential. Nature was but one actor in the Helena story, albeit a crucial one. [24] Still, an environmental interpretation of the Helena campaign is instructive because, as historian Paul Sutter writes, it demonstrates that “battlefield tactics and outcomes are not merely the products of military minds and soldierly actions but also of the dynamics of weather, terrain, soil type, disease, and other nonhuman entities and forces.” [25] In the summer of 1863, nature molded the actions and intentions of both armies and played a fundamental part in a campaign that ensured federal control of the Mississippi River, preserved the Union foothold in eastern Arkansas, and paved the way for federal control of Little Rock only two months later.

- [1] W.A. Jenkins, “A Leaf From Army Life” (Read December 8, 1887), in Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, Illinois, 3 (1899), republished in 70 vols., Wilmington, NC: Broadfoot Publishing, 1992-1995, 12:444. Jenkins served as a lieutenant-colonel in the 5th Kansas Cavalry during the battle of Helena. In 1860, Helena’s population included 1,024 whites and 527 blacks, making it slightly less than half the size of Little Rock, Arkansas’s state capital. United States Bureau of the Census, The Statistics of the Population of the United States, From the Original Returns of the Ninth Census, (June 1, 1870) Under the Direction of the Secretary of the Interior, by Francis A. Walker, Superintendent of Census (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1872), 87.

- [2] There are no books on the Helena campaign. Scholarly works that consider it in detail include Edwin C. Bearss, “The Battle of Helena, July 4, 1863,” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 20 (Autumn 1961): 256-297; Albert Castel, General Sterling Price and the Civil War in the West (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1968), chap. 8; Warren E. Grabau, Ninety-Eight Days: A Geographer's View of the Vicksburg Campaign (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2000), chap. 40; Gregory J. W. Urwin, “A Very Disastrous Defeat: The Battle of Helena, Arkansas,” North & South 6 (December 2002): 26-39; G. David Schieffler, “Too Little, Too Late to Save Vicksburg: The Battle of Helena, Arkansas, July 4, 1863” (M.A. Thesis, University of Arkansas, 2005); Mark K. Christ, Civil War Arkansas, 1863: The Battle for a State (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010), chap. 4; Christ, “The Battle of Helena,” Blue & Gray 32, no. 4 (2016): 6-23, 42-47; Thomas W. Cutrer, Theater of a Separate War: The Civil War West of the Mississippi River, 1861–1865 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), chap. 12; and Schieffler, “Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign” (PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2017).

- [3] Environmental Civil War history is a rapidly growing field. The best succinct survey of the field is Brian Allen Drake, “New Fields of Battle: Nature, Environmental History, and the Civil War,” in Drake, ed., The Blue, the Gray, and the Green: Toward an Environmental History of the Civil War (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2015), 1-15. For a longer historiographical review, see Lisa Brady, “From Battlefield to Fertile Ground: The Development of Civil War Environmental History,” Civil War History 58, no. 3 (Sept. 2012): 305-321. Important works that have appeared since the publication of Brady’s essay include Kathryn Shively Meier, Nature's Civil War: Common Soldiers and the Environment in 1862 Virginia (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2013); Drake, ed., The Blue, the Gray, and the Green; Matthew M. Stith, Extreme Civil War: Guerrilla Warfare, Environment, and Race on the Trans-Mississippi Frontier (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2016); and Adam H. Petty, “Wilderness, Weather, and Waging War in the Mine Run Campaign,” Civil War History 63 (March 2017): 7-35. See also Judkin Browning and Timothy Silver’s forthcoming The Civil War: An Environmental History, Kenneth W. Noe’s forthcoming book on weather and the Civil War, and Megan Kate Nelson’s forthcoming Path of the Dead Man: How the West was Won—and Lost—during the American Civil War.

- [4] On June 9, 1863, General Sterling Price wrote General Theophilus Hunter Holmes that “were a movement conducted with celerity and secrecy . . . I entertain no doubt of your being able to crush the foe” at Helena. United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 vols. in 128 parts (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 22, part. 2, p. 863 (hereafter cited as O.R., I, 22, pt. 2, 863).

- [5] Scholars are divided on the definition of “nature,” especially humans’ place within it. Some argue that humans are a part of nature and thus cannot be separated from it, while others assert that because humans have altered the natural environment so significantly throughout history, there is little that is “natural” in nature anyway, so it is futile to try to remove humans from the equation. While these arguments have merit, for the sake of clarity, my definition of “nature” does not include humans. Rather, like Lisa M. Brady, I define nature as “the nonhuman physical environment in its constituent parts or as a larger whole.” Moreover, I use “natural environment” and “environment” as synonyms for “nature.” Brady, War upon the Land: Military Strategy and the Transformation of Southern Landscapes during the American Civil War (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2012), 12-13.

- [6] Grabau, Ninety-Eight Days, 477; Sam Morgan, “Blue Delta: The Union Occupation of Helena, Arkansas, During the Civil War” (M.A. Thesis, Arkansas State University, 1993), 4-5; William L. Shea and Terrence J. Winschel, Vicksburg is the Key: The Struggle for the Mississippi River (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003), 28; O.R., I, 1, 685-6, 689. On Curtis’s remarkable post-Pea Ridge march across Arkansas, see Robert G. Schultz, The March to the River: From the Battle of Pea Ridge to Helena, Spring 1862 (Iowa City: Camp Pope Publishing, 2014); and William L. Shea, “A Semi-Savage State: The Image of Arkansas in the Civil War,” in Civil War Arkansas: Beyond Battles and Leaders, Anne J. Bailey and Daniel E. Sutherland, eds. (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000), 85-100.

- [7] Schieffler, “Too Little, Too Late,” 7-42; A.F. Sperry, History of the 33d Iowa Infantry Volunteer Regiment, 1863-6, Gregory J.W. Urwin and Kathy Kunzinger Urwin, eds. (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1999), 14. Helena, like most places in the Mississippi Valley during the Civil War, was a disease-ridden place. Rhonda M. Kohl has shown that the soldiers stationed in Helena between July 1862 and January 1863 were much more likely to die of typhoid, intestinal disease, and malaria than were their Union counterparts elsewhere. However, because Kohl’s study ends in January 1863, she does not consider the role of disease in the summer 1863 Helena campaign. My research suggests that because sickness plagued both the Union and Confederate armies during the campaign, it disadvantaged neither side more than the other and thus was not decisive in its outcome. See Rhonda M. Kohl, “‘This Godforsaken Town’: Death and Disease at Helena, Arkansas, 1862-63,” in Civil War History 50 (June 2004): 109-144.

- [8] O.R., I, 22, pt. 2, 867-8; and Ibid., I, 22, pt. 1, 407.

- [9] O.R., I, 22, pt. 1, 409; and Ibid., I, 22, pt. 2, 877; Urwin, “A Very Disastrous Defeat,” 29.

- [10] O.R., I, 22, pt. 1, 409-13; and Ibid., I, 22, pt. 2, 886-99; William H.H. and J.S. Shibley to Parents, June 28, 1863, in Ruie Ann Smith Park, ed., The Civil War Letters of the Shibley Brothers, William H.H. and John S., to Their Dear Parents in Van Buren, Arkansas (Fayetteville, AR: Washington County Historical Society, 1963), Letter No. 40; Mark K. Christ, ed., “‘We Were Badly Whiped’: A Confederate Account of the Battle of Helena, July 4, 1863,” in Arkansas Historical Quarterly 69 (Spring 2010): 49-50. For an excellent first-person description of the Confederate struggles to reach Helena, see Cynthia DeHaven Pitcock and Bill J. Gurley, eds., ‘I Acted from Principle’: The Civil War Diary of Dr. William M. McPheeters, Confederate Surgeon in the Trans-Mississippi (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2002), 35-37.

- [11] Fort Curtis was not, as the name implies, a military administration center. Rather, it was a mostly subsurface structure containing two powder magazines and a well. On the surface, it was equipped with several large siege guns, the exact locations and specifics of which have been disputed. Archaeological research conducted in the late 1960s revealed that the fort was equipped to hold four 24-pound Barbette guns, one in each corner, with three additional guns mounted somewhere along the fort’s outer walls. Joshua Underhill, who visited the fort in November 1863, said it was “a pretty substantial fortification” occupying “one city square” and armed with “large guns,” the largest being a 42-pounder. Burney McClurkan, “Archeological Investigation at Fort Curtis, Helena, Arkansas,” in Phillips County Historical Quarterly 6 (June 1968): 3-7; Christopher Morss, ed., A Civil War Odyssey: The Personal Diary of Joshua Whittington Underhill, Surgeon, 46th Regiment, Indiana Volunteer Infantry, 23 October 1862-21 July 1863 (Lincoln Center, MA: Heritage House Publishers, 2000), 16.

- [12] Sperry, History of the 33d Iowa, 37; Urwin, “A Very Disastrous Defeat,” 27; Lurton Dunham Ingersoll, Iowa and the Rebellion: A History of the Troops Furnished by the State of Iowa to the Volunteer Armies of the Union, Which Conquered the Great Southern Rebellion of 1861-5 (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1866), 616; O.R., I, 22, pt. 1, 387-88; William F. Vermilion to “My Darling” Mary Vermilion, June 4, 1863, in Donald C. Elder III, ed., Love Amid the Turmoil: The Civil War Letters of William and Mary Vermilion (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2003), 123.

- [13] David D. Porter to U.S. Grant, June 18, 1863, in John Y. Simon, ed., The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, 31 vols. (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1979), 8:390; United States Navy Department, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, 30 vols. and index (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1894-1922), Series I, volume 25, p. 227 (hereafter cited as O.R.N., I, 25, 227 ). The Tyler’s executive officer later claimed to have fired 413 rounds during the battle, killing or wounding about six hundred men. Prentiss was so impressed by the Tyler’s contribution that he recommended its commander, Lieutenant Commander James M. Pritchett, for a promotion following the battle. Most of the previous scholarship on the battle of Helena has highlighted the crucial, if not decisive role of the Tyler. However, Steven W. Jones argues that the Tyler’s shells were more psychologically overwhelming to the rebels than they were physically devastating; O.R.N., I, 25, 229; O.R., I, 22, pt. 1, 391-2; Steven W. Jones, ed., “The Logs of the U.S.S. Tyler,” in Phillips County Historical Quarterly 15 (March 1977): 23-38.

- [14] See, for example, O.R., I, 22, pt. 2, 317, and Benjamin M. Prentiss to U.S. Grant, April 25, 1863, in Simon, The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, 8:106; O.R., I, 24, pt. 3, 445; and Ibid., I, 22, pt. 1, 387-8; and Ibid., I, 22, pt. 2, 352; John S. Morgan, “Diary of John S. Morgan, Company G, Thirty-Third Iowa Infantry,” in Annals of Iowa 13 (January 1923): 492.

- [15] O.R., I, 22, pt. 1, 387-8.

- [16] Michael E. Banasik, ed., Missouri Brothers in Gray: The Reminiscences and Letters of William J. Bull and John P. Bull (Iowa City, IA: Camp Pope Bookshop, 1998), 54; Theophilus H. Holmes to Jefferson Davis, July 14, 1863, in the Correspondence of General T. H. Holmes, 1861-1864, Records of the War Department, Collection of Confederate Records, Record Group 109, National Archives and Records Administration; O.R., I, 22, pt. 1, 409.

- [17] Ibid., I, 22, pt. 1, 409-10.

- [18] Ibid., I, 22, pt. 1, 424; Schieffler, “Too Little, Too Late,” 56-64.

- [19] O.R., I, 22, pt. 1, 410, 413.

- [20] O.R., I, 22, pt. 1, 424, 431; William H.H. and J.S. Shibley to Parents, July 23, 1863, in Park, The Civil War Letters of the Shibley Brothers, Letter No. 42.

- [21] It is important to note that it was Parsons, not Holmes, who described this incident in his battle report. However, Holmes did admit that most of his loss in prisoners “resulted from not restraining the men after the capture of Graveyard Hill from advancing into the town, where they were taken mainly without resistance.” O.R., I, 22, pt. 1, 421-2, 410-11.

- [22] John A. Savage, Jr. to Hon. T. O. Howe, August 20, 1863, Frederick C. Salomon Papers, Wisconsin Veterans Museum Research Center, Madison, WI.

- [23] Christ, ed., “‘We Were Badly Whiped’, 50.

- [24] I am persuaded by military historian Harold Winters’s contention that “one makes a mistake by becoming deterministic regarding geography and the outcome of battles and wars. But when considered along with all the other variables and human decisions involved, there are occasions when physical or cultural environmental factors are paramount in the success or failure of soldiers, armies, and their commanders.” Harold A. Winters, “The Battle That Was Never Fought: Weather and the Union Mud March of January 1863,” Southeastern Geographer 31 (May 1991): 37.

- [25] Paul S. Sutter, “Waving the Muddy Shirt,” in Drake, ed., The Blue, the Gray, and the Green, 227.

If you can read only one book:

Urwin, Gregory J. W. “A Very Disastrous Defeat: The Battle of Helena, Arkansas,” in North & South 6 (December 2002): 26-39.

Books:

Banasik, Michael E., ed. Missouri Brothers in Gray: The Reminiscences and Letters of William J. Bull and John P. Bull. Iowa City, IA: Camp Pope Bookshop, 1998, chap. 9, “Battle of Helena, Arkansas (July 4, 1863)”.

Bearss, Edwin C. “The Battle of Helena, July 4, 1863,” in Arkansas Historical Quarterly 20 (Autumn 1961): 256-97.

Brent, Joseph E. and Maria Campbell Brent. “Civil War Helena: A Research Project and Interpretive Plan.” Versailles, KY: Mudpuppy and Waterdog, 2009.

Castel, Albert. General Sterling Price and the Civil War in the West. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1968, chap. 8, “Helena”.

Christ, Mark K. Civil War Arkansas, 1863: The Battle for a State. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010, chap. 4, “‘A Grivous Calamity’: The Battle of Helena”.

Christ, Mark K., ed. Rugged and Sublime: The Civil War in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

Cutrer, Thomas W. Theater of a Separate War: The Civil War West of the Mississippi River, 1861–1865. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017, chap. 12, “Courage and Desperation Rarely Equaled: The Rebel Assault on Helena, 4 July 1863”.

DeBlack, Thomas A. With Fire and Sword: Arkansas, 1861-74. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003, chap. 3, “‘The Very Spirit of Destruction’: The War in 1863”.

Grabau, Warren E. Ninety-Eight Days: A Geographer's View of the Vicksburg Campaign. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2000, chap. 40, “Forlorn Hope: Battle of Helena”.

Popchock, Barry, ed. Soldier Boy: The Civil War Letters of Charles O. Musser, 29th Iowa. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1995.

Schieffler, G. David. “Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2017.

Sperry, A. F. History of the 33rd Iowa Infantry Volunteer Regiment, 1863–6. Gregory J. W. Urwin and Cathy Kunzinger Urwin, eds. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1999, chap. 5 and 6.

Thompson, Alan, ed.

“‘Frank and out spoken in my disposition’: The Wartime Letters of Confederate General Dandridge McRae,” in Arkansas Historical Quarterly 72 (Winter 2013): 333-65.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

The Arkansas Civil War Sesquicentennial Commission has resources relating to the Civil War in Arkansas.

Civil War Helena provides information, links, and ideas for exploring Civil War Helena.

The remains of the battlefield at Helena are all in private hands and scattered throughout the town. Battlefield Wanderings provides directions for a walking tour.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.