The Second Battle of Bull Run

by Michael Burns

In late August 1862, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia faced Pope’s thirty-two thousand-man Army of Virginia across the Rappahannock River. Fearing he would soon be outnumbered if McClellan’s Army of the Potomac, then evacuating its position on the Peninsula east of Richmond, joined with Pope, Lee made the bold decision to split his force in the face of the enemy. Over August 25 and 26, he sent Jackson’s twenty-five thousand troops on a flank march toward Manassas Junction—the main Union supply depot in northern Virginia—to dislodge Pope from his position by cutting his supply and communication line to the Union capital. Lieutenant General James Longstreet kept his thirty thousand strong force in place to hold Pope’s attention. Jackson’s men captured and destroyed the union supply depot on August 27, forcing Pope to fall back toward the junction. The Battle opened late on August 28 when Jackson, in position close to Brawner’s Farm near the old Bull Run battlefield, attacked a Union division marching toward Centerville on the Warrenton Turnpike. The fighting brought Pope and the rest of his army to confront Jackson on ground of Jackson’s choosing with the main battle commencing on August 29. By the end of the day the two forces were in position facing each other. Unbeknownst to the Federals, Longstreet had been marching to join Jackson and he came into position late on August 29. On August 30, the fighting began again with Pope launching attacks on Jackson, still not understanding that Longstreet was on the battlefield positioned on the Federal left flank. Longstreet launched his attack on Pope late in the afternoon. For an hour and a half, about seven thousand Union and fifteen thousand Confederate troops fought a furious battle along the slopes of Chinn Ridge, with the majority of brigades suffering fifty percent or more casualties. Although overwhelmed, the Union forces bought enough time for Pope to set up a defensive position on Henry Hill. Longstreet restarted the assault after a brief lull on Chinn Ridge. Until the sun set around 8:00 p.m. on August 30, Longstreet’s wing threw itself against the makeshift defensive position on Henry Hill, where the Union line held. Pope, recognizing his failure, abandoned the field along the banks of Bull Run retreating back toward Washington, D.C., that night. The Battle of Second Bull Run marked the culmination of a summer of successes for the main Confederate field army in the east. The Army of Northern Virginia had defeated the Union Army of the Potomac outside of Richmond then proceeded to almost destroy the Army of Virginia on the fields near Bull Run. Lee’s force had turned the momentum of the war on its head, marking the first major hope for the Confederates to end the conflict in victory, and announcing the arrival of what could be considered the Confederate triumvirate—Lee above Longstreet and Jackson—in the Army of Northern Virginia. The Union defeat highlighted Lincoln’s struggle to find capable officers and commanders to fight the Confederates in Virginia. Most significantly, the Battle of Second Bull Run opened the way for Lee’s first attempt at invading Union held territory, setting the stage for further bloodshed along the banks of another small creek named Antietam.

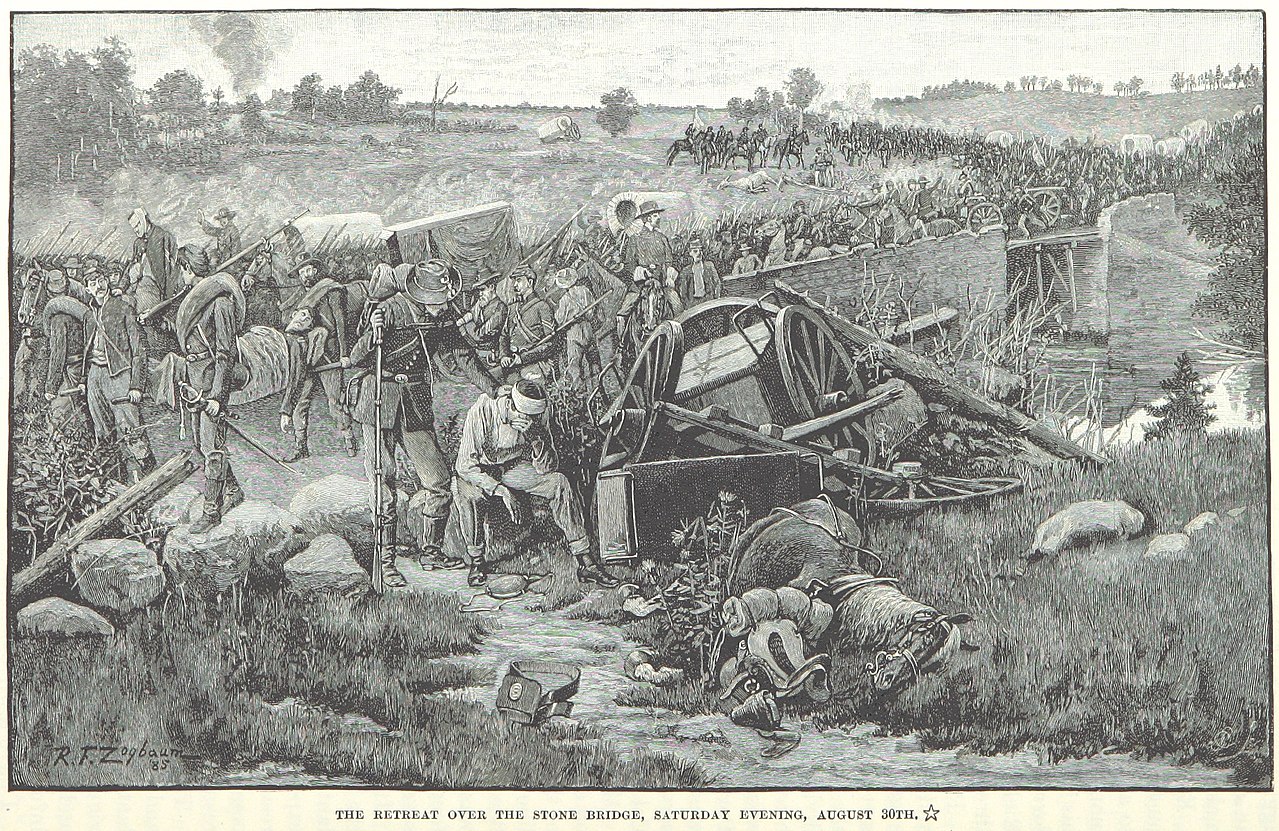

The Retreat Over the Stone Bridge, Saturday Evening, August 30 Linecut by Rufus F. Logbaum, 1865 from Century Magazine May 1886

Image courtesy of: The Library of Congress

On September 3, 1862, Dennis Tuttle, while writing to his wife from Yorktown, Virginia, lamented his inactivity as part of the 20th Indiana Infantry Regiment. Most of the regiment, according to Tuttle, had made their way to northern Virginia, where they were now engaged in another major battle. Although having been part of Major General George Brinton McClellan’s Army of the Potomac and their campaign along the York Peninsula toward Richmond, Tuttle longed for the action. “I am out of all patience lying here doing nothing while there is such exciting times where the reg[imen]t is,” he wrote. By that day, he had “anticipated some hard fighting in the neighborhood of Manassas . . . That portion of the ‘Old Dominion,’” he penned, “will be thoroughly drenched in blood before the fighting will cease.” In the aftermath of the bloodshed, he believed “the rebel Army will be pretty much disposed of before they get away from before Washington.”[1] Little did Tuttle know that while he composed the letter to his wife, the Confederate forces were already threatening the Union capital of Washington, D.C., after their victory at Second Manassas. The Battle of Second Manassas or Bull Run capped a long summer of victories for the Confederates and reversals for the Union. Fought between the Seven Days Battles—the first operation where Confederate troops in Virginia were under Robert E. Lee’s command—and the Battle of Antietam—the single bloodiest day in American military history—Second Bull Run was a key point in the long summer of 1862.[2]

Second Bull Run began with a confused army searching for an elusive enemy. Late in the afternoon of August 28, 1862, Brigadier General Rufus King’s exhausted division of six thousand Union soldiers rested in the trees along the Warrenton Turnpike—the main macadamized road through northern Virginia between Warrenton, Virginia, and Washington, D.C. Throughout the day, King’s troops marched and countermarched between Warrenton and Manassas Junction due to the confusion among the Union command over the location of the Confederate forces. After resting for a few hours, the troops reformed along the turnpike in preparation to move on the small town of Centreville. King’s troops, along with approximately forty thousand additional federal soldiers in the Army of Virginia under Major General John Pope, searched for the elusive wing of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia under Lieutenant General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson.[3] Three days before, Jackson’s twenty-five thousand men had disappeared from the Union front along the Rappahannock River. For almost three weeks, Pope successfully held General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at bay along that main waterway that marks the southern border of northern Virginia. Desperate to destroy Pope’s force before the arrival of McClellan’s massive Union Army of the Potomac, which was evacuating its position along the Peninsula east of Richmond to reinforce Pope’s force of thirty-two thousand men. Fearing that the combined Union armies would soon outnumber his over two to one, Lee made the bold decision to split his force in the face of the enemy. He sent Jackson’s twenty-five thousand troops on a flank march toward Manassas Junction—the main Union supply depot in northern Virginia—to dislodge Pope from his position by cutting his supply and communication line to the Union capital. Meanwhile, Lieutenant General James Longstreet kept his thirty thousand strong force in place on the Rappahannock to hold Pope’s attention.[4]

Initiating his march on August 25, Jackson’s soldiers marched fifty-four miles in only thirty-six hours arriving just south of Manassas Junction on August 26. The following day, Jackson captured and destroyed the Union supply depot, forcing Pope to fall back toward Manassas Junction.[5] Pope believed he could finally capture the vaunted Stonewall Jackson—turning himself into a national hero—while also destroying half of Lee’s army before the two wings could reunite. By midday of August 28, however, Pope reached the smoldering ruins of his supply depot. The solitary sign of Jackson’s presence the day before was a number of Confederate stragglers and stories from local civilians. Informed that Jackson had moved to the small town of Centreville along the Warrenton Turnpike, Pope ordered all his troops to converge on the hamlet.[6]

King’s six thousand troops slowly made their way toward Centreville in the hopes of cutting Jackson off from the west. Although exhausted from their long marches and countermarches, many of the officers and men in the division had dreams of glory in capturing Jackson’s force—one that had created massive havoc for Abraham Lincoln’s administration in the Shenandoah Valley by its maneuvers throughout the spring of 1862. Though the soldiers prepared for a fight in Centreville, King’s ill health left the division with little direction. Late on August 27, King, who suffered from epilepsy, experienced a seizure. Instead of leading his men the afternoon of August 28, King was left recovering in an ambulance wagon to the rear of his troops. His four brigade commanders, Brigadier General John Gibbon, Brigadier General Marsena Rudolph Patrick, Brigadier General Abner Doubleday, and Brigadier General John Porter Hatch, bickered over who commanded the division in King’s absence. With no direction other than Pope’s original order to move on Centreville, the officers and six thousand foot soldiers soon discovered the difficulties of Civil War command structures with the top officer incapacitated.[7]

Still, King’s troops continued this march towards the small town along the Warrenton Turnpike. Shortly after the division reformed on the road and re-initiated their march, one Union officer reported spotting a lone horseman riding back and forth along a low ridge just north of the turnpike. As he described it, the soldier believed the man on the horse was watching the Union division. Little did the trooper know that he had just spotted Stonewall Jackson.[8]

Although the Union command believed Jackson had taken up positions around Centreville, he had decided to place his men along familiar terrain instead. Having been a major hero in the Battle of First Bull Run, Jackson had knowledge of the landscape near the small creek where he had fought the year before. He ordered all his troops to gather in the fields west of the creek, but Jackson’s secretive command process and vague orders caused confusion for one of his subordinates. As a result, part of his wing ended up in Centreville on the night of August 27, which led to some of the uncertainty for the Union officers on the following day. After reuniting his own soldiers on the morning of August 28, Jackson waited for word from Longstreet’s wing of the army before moving against the Union forces. Just about the same time that Pope arrived at his smoldering supply depot, Jackson received a note from Longstreet informing Jackson that his thirty thousand troops were within a days’ march of Jackson’s position near the Brawner Farm known as Stony Ridge. Now knowing Longstreet could get to the field within twenty-four hours, Jackson looked for an opportunity to spring a trap on the Union forces.[9]

After a couple of hours hoping to find an opening, Jackson spotted King’s division on the Warrenton Turnpike. Having all twenty-five thousand men of his wing within two miles of the Brawner farmhouse, Jackson believed he could destroy the much smaller Union unit. The timing, however, made his decision tricky. It was already after 4:00 p.m. and the sun typically set by eight at night in Virginia in late August. Aware that he needed to move quickly, Jackson immediately rode back to Stony Ridge and calmly ordered his officers: “Bring out your men, gentlemen!”[10] Surprised at the order, Jackson’s subordinates and troops scrambled to prepare for the attack, but not in a speedily enough fashion for Jackson. He feared that his opportunity to strike was rapidly passing. So, instead of waiting for his infantry, Jackson threw forward a single battery of artillery—four pieces total. Opening fire on King’s division around 5:30 p.m., the cannon fire quickly garnered the attention of the Union force, scattering the six thousand men along the turnpike.

Two brigades, Gibbon’s Black Hat Brigade (which would soon become more famous as the Iron Brigade) and Doubleday’s brigade of New Yorkers and Pennsylvanians, took cover in the woods to the southeast of the Brawner farmhouse. Hatch and Patrick would keep their brigades under cover and out of the fight for the rest of the evening. Working quickly, Gibbon believed they had stumbled on horse artillery—cannons that rode with the cavalry. Not expecting to confront any Confederate infantry, Gibbon decided to send his most experienced regiment, the 2nd Wisconsin, forward to capture the guns. Just as the 2nd Wisconsin emerged from the woods, the cannons disappeared from the low ridge, only to be replaced by the veteran troops of the Stonewall Brigade—the brigade of Virginians who fought with Jackson at First Manassas. Soon realizing his mistake, Gibbon committed his three other regiments, the 6th and 7th Wisconsin, and the 19th Indiana, to the fray, officially opening the Battle of Second Bull Run.[11]

Jackson quickly responded committing additional troops, while Doubleday added parts of two regiments to assist Gibbon. Yet, out of his twenty-five thousand troops, Jackson only brought about 4,500 on the field to fight the approximately 2,500 Union troops. With the sun setting and little direction, the two lines of infantry, at points no further than eighty yards and as close as twenty yards apart, blasted away at each other. The slugfest lasted for two hours until the Confederate officers found a route around the Brawner farmhouse to outflank the Union position. The federals fought their way back to the tree line of the Brawner woods and the brief fight came to a close just as the sun set, allowing the two sides to fall back and recover for the larger battle to come.[12]

Out of the approximately seven thousand soldiers involved in the fight at the Brawner Farm, two thousand, including two of Jackson’s brigade commanders, Major General Richard Stoddert Ewell and Brigadier General William Booth Taliaferro, were counted as casualties. Still, Jackson achieved what he wanted. Pope was now committed to fighting on ground of Jackson’s choosing. Additionally, King, who had recovered from his seizure by the night of August 28, made the decision to abandon the position along the Warrenton Turnpike, opening the road to Longstreet’s thirty thousand soldiers only ten miles away. Though brief, the fighting on August 28 set the stage for the next two days of battle.[13]

By the following morning, having received word about the fighting, Pope ordered his men toward Stony Ridge believing he could still destroy Jackson’s wing before Longstreet’s arrival. Completely unaware of Longstreet’s presence within less than a days’ march from the Bull Run Mountains, Pope concentrated all his troops on Jackson’s new position along an unfinished railroad grade that ran along the front of the ridge. Judging that he could hold the position until Longstreet arrived, Jackson placed his men on the defensive waiting for Pope to launch his assault. Pope quickly complied.

Even before his entire army arrived in the area, Pope’s officers started to probe at Jackson’s line. By 10:00 in the morning, multiple Union assaults, some made by mistake, struck the Confederate position. Although basically a ready-made trench for the rebel forces, the unfinished railroad contained a number of weak points where it leveled out with the land. A number of Union commanders watched as their soldiers inadvertently slammed into those vulnerable spots creating brief breakthroughs throughout the day. Sadly for the Union brigades that broke through, they received little to no support, which quickly ended their successes.[14]

Eventually, around midday, Pope arrived on the field during a lull in the fighting. After briefly scouting the unfinished railroad and receiving reports from his subordinates, Pope decided to try to turn the right flank of Jackson’s position just north of the Brawner Farm. Having received reinforcements from McClellan’s Army of the Potomac, specifically Major General Samuel Peter Heintzelman’s III corps and Major General Fitz John Porter’s V corps, Pope hoped to use the newly arrived troops to his advantage. He ordered most of his army to prepare for diversionary assaults against Jackson’s front while Porter’s V corps would strike Jackson’s right. By early afternoon, the assaults initially meant as diversions started near Jackson’s left near Sudley Church. Like the morning attacks, these frontal offensives found brief success, but quickly sputtered out with a lack of support.[15]

While many Union troops sacrificed themselves in these operations against Jackson’s front, Pope became increasingly frustrated with Porter’s lack of actions. Although Pope provided conflicting orders to Porter, he expected the V corps to attack by late afternoon in order to overrun the unfinished railroad grade. But Porter, confused from the orders that did not directly tell him to assault Jackson’s position, Porter moved cautiously and soon found himself opposing what he believed was Longstreet’s thirty thousand strong wing. While confusion reigned between the Federal commanders both as to the number of Confederate soldiers to Porter’s front and his overall objective, Pope still expected the V corps to attack Jackson’s position. By the time night fell, however, Porter remained in position south of the Confederate line while the rest of the Union force faced Jackson and Longstreet. Unfortunately for Porter, partly due to his friendship with McClellan and his previous opposition to Pope’s appointment, his actions on the afternoon of August 29 led to his court martial in late 1862, which was reversed only after some of Longstreet’s veterans testified to Congress twenty-five years after the battle.[16]

Second Battle of Bull Run Position of Troops at 6 p.m. Friday Aug. 29th 1862.

by Sneden, Robert Knox.

Map Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The Union command remained confused throughout August 30 as well. Despite telegraphing Washington, D.C., that he was on the verge of victory, Pope was unaware of the full situation. He still thought that Longstreet was not on the field. Other conflicting reports made it difficult for him to ascertain Longstreet’s position fully. And these same reports made it seem that Jackson had decided to retreat. In reality, the Confederate’s had strengthened their position with additional artillery and through maneuvering their infantry to reinforce weak points. Yet, Pope believed that one last mass assault would break the Confederate line and achieve his victory.[17]

In order to launch this attack, Pope wanted to use the freshest troops he had on hand, which he thought came from Porter’s V corps. That morning, despite Porter’s objections, Pope ordered Porter to set his ten thousand men in position along the ridges in front of Jackson’s center—a spot in the unfinished railroad grade known as the Deep Cut. By early afternoon, Porter had the majority of his corps in position. Almost two thousand of his men, however, ended up in Centreville as a result of unclear orders, leaving only eight thousand to assault the Confederate center. Porter devised a plan to send six thousand troops through the open fields and up Stony Ridge to break Jackson’s line. He held the other two thousand to exploit any breakthroughs that afternoon. It quickly became clear that the two thousand reserves were unnecessary.[18]

Battle of Second Manassas August 30, 1862

Map Courtesy of: The American Battlefield Trust

Starting the attack around 3:00 p.m., Porter threw his six thousand troops at the Deep Cut. Within minutes they started receiving infantry fire. Suddenly, an artillery barrage consisting of thirty-six guns bombarded the charging federals from the clearings to the soldiers’ left. One soldier described the artillery bombardment as making the ground look like a pond during a rainstorm with shrapnel and earth flying in all directions. Some of the Union soldiers, specifically the 24th and 30th New York, reached the Confederate position. But they were quickly forced to take cover along the front of the embankment between the Deep Cut and the front of Stony Ridge. Only a minor breakthrough provided any hope for the Union assault. Within thirty minutes and after suffering two thousand casualties, the Union officers ordered a general retreat. The Union soldiers who survived the attack on the Deep Cut hastily fled for safe ground near the Union center on Dogan Ridge.[19]

One Union officer feared the scene he was witnessing in the aftermath of the afternoon assault. Major General Irvin McDowell commanded the Army of Virginia’s III corps at Second Bull Run but had achieved infamy as the commander of Union forces during the defeat at First Manassas one year before. McDowell, seeing panicked, retreating troops, remembered the chaos of the flight after First Bull Run. Hoping he could prevent a second terrified retreat, McDowell decided to remove seven thousand of his troops from the area known as Chinn Ridge on the Union left to reinforce the federal center on Dogan Ridge. In doing so, he left only 2,200 New York and Ohio troops along the ridges and hills south of the Warrenton Turnpike. These six regiments now faced Longstreet’s thirty thousand Confederates. Recognizing his opportunity and having been chomping-at-the-bit to launch an attack for two days, Longstreet ordered all his men forward against the weakened Union left.[20]

Believing he could capture the prominent rise of Henry Hill—the scene of heaviest fighting during the first battle—and in the process cut off the Army of Virginia, Longstreet quickly pushed his men forward. Starting around 4:30 in the afternoon, the Confederate wave, led by the famed Texas Brigade, rapidly overwhelmed two New York regiments, causing about fifty percent casualties for the federals in only a matter of minutes. McDowell soon realized his mistake and immediately began throwing reinforcements in the way of Longstreet’s advance. While doing so, he finally convinced Pope of Longstreet’s arrival and the danger it now created, forcing Pope to fall back to a new defensive position.[21]

Shortly after destroying the two New York regiments, the Texas Brigade overran two fresh regiments and a Union battery pushing closer to the twelve hundred Ohioans at the crest of Chinn Ridge. Their original success had exhausted the Texans, however, and the Ohio troops briefly stopped their advance. Still, with fresh brigades and regiments arriving in a piecemeal fashion from Longstreet’s wing, the Confederates started pouring over the ridge. By holding for about fifteen minutes, despite being outnumbered over two to one, the Ohioans bought just enough time for Union reinforcements to stall the attack further along Chinn Ridge. For an hour and a half, about seven thousand Union and fifteen thousand Confederate troops fought a furious battle along the slopes of Chinn Ridge, with the majority of brigades suffering fifty percent or more casualties. Although overwhelmed, the Union forces bought enough time for Pope to set up a defensive position on Henry Hill.[22]

Longstreet continued the assault even after the bloodshed on Chinn Ridge. Needing to wait for reinforcements, Longstreet held his men for approximately twenty minutes. Once his fresh troops got in position around 6:30 p.m., Longstreet restarted his attack. For another hour and a half, until the sun set around 8 p.m. on August 30, Longstreet’s wing threw itself against the makeshift defensive position on Henry Hill. Although the Union line bent, it held. Once the Union cavalry ended a Confederate cavalry foray to capture the Warrenton Turnpike, Pope, recognizing his failure, abandoned the field along the banks of Bull Run retreating back toward Washington, D.C., that night. With Pope’s retreat, the Confederate victory at Second Bull Run was secure. As one Union soldier described, “This is the darkest hour of our Country’s peril.”[23]

Second Battle of Bull Run Position at 6 PM August 30th 1862 by Robert Knox Sneden.

Map Courtesy of: The Library of Congress

The Battle of Second Bull Run marked the culmination of a summer of successes for the main Confederate field army in the east. The Army of Northern Virginia had defeated the Union Army of the Potomac outside of Richmond then proceeded to almost destroy the Army of Virginia on the fields near Bull Run. Having started the summer only five miles outside of its capital, Lee’s force had turned the momentum of the war on its head, marking the first major hope for the Confederates to end the conflict in victory. On the opposing side, Abraham Lincoln and his administrators witnessed their lowest point in the war effort in its first year. Although Lincoln had already drafted a version of the Emancipation Proclamation, on the recommendation of his cabinet, he wanted to wait for a Union victory before releasing it publicly. The failure of Pope’s troops to deliver that victory delayed Lincoln’s effort at defining the end of the institution of slavery as a key Union war aim. He would only have to wait another three weeks before making it public. The defeat at Second Bull Run also caused the support of northern civilians to waver during that summer and fall. Having consumed news from the front on a daily basis, they saw growing casualty lists with little success to justify the loss of life. Northern public support for the war started to wane, causing a rise in the Copperhead movement and threatening the continuation of the war.

The fighting in northern Virginia over those three days also indicated the arrival of what could be considered the Confederate triumvirate in the Army of Northern Virginia. The fight in late August was the first time the high command of the newly reorganized army, Lee above Jackson and Longstreet, worked in conjunction to fight a major Union force. According to historian John J. Hennessy, the three generals “assumed their respective roles” during the battle: the aggressive and daring Jackson, the reactive and deadly Longstreet, and the audacious “architect of victory” Lee. “Each would act in his respective capacity again,” Hennessy writes, “but in no other campaign would they do so simultaneously.”[24] The Army of Northern Virginia found its identity during this campaign.

The Union defeat highlighted Lincoln’s struggle to find capable officers and commanders to fight the Confederates in Virginia. Having taken command of a makeshift army, Pope was unable to maintain a sense of command or order in his army throughout the campaign. He had difficulty effectively communicating with his subordinates. Even when he did provide clear orders, a number of his subordinates ignored his commands. Until 1864 with the arrival of Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, federal forces in Virginia rarely experienced success as commanders came and went.[25]

Most significantly, the Battle of Second Bull Run opened the way for Lee’s first attempt at invading Union held territory. His army had just defeated two major Union forces and now sat on the doorstep to the Union capital of Washington, D.C. Instead of trying a direct attack, however, Lee decided to move into Maryland with the hopes of eventually reaching Pennsylvania to relieve pressure on Virginia’s farmers and create fear and chaos in the northern population. On September 3, 1862, while the two Union armies were being reorganized and combined into the Army of the Potomac under McClellan’s command, Lee pushed the Army of Northern Virginia across the Potomac River and into western Maryland. With that movement, Lee set the stage for the bloodiest single day in U.S. military history, September 17, 1862, along the banks of another small creek named Antietam.[26]

- [1] Dennis Tuttle to “My Dear Wife,” September 3, 1862, Correspondence Sent 1862. Transcripts, Folder 6, Box 1, Dennis Tuttle Papers, 1862–1995, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

- [2] For more on McClellan’s failed Peninsula Campaign and the Seven Days Battles, see Stephen W. Sears, To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign (New York: Ticknor and Fields, 1992). For more on the Battle of Antietam, see James M. McPherson, Crossroads of Freedom: Antietam, Pivotal Moments in American History series (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002).

- [3] For more on the background of Major General John Pope, see Peter Cozzens, General John Pope: A Life for the Nation (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000). For more on the creation of the Army of Virginia and the Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1862, see John H. Matsui, The First Republican Army: The Army of Virginia and the Radicalization of the Civil War (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2017), Robert K. Krick, Conquering the Valley: Stonewall Jackson at Port Republic (New York: Morrow, 1996), and Peter Cozzens, Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson’s Valley Campaign (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008).

- [4] General Robert E. Lee to Adjutant General Samuel Cooper, 3 September 1862, in United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 vols. in 128 parts (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 12, part 2, p. 552 (hereafter cited as O.R., I, 12, pt. 2, 552); John J. Hennessy, Return to Bull Run: The Campaign and Battle of Second Manassas (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993), 38–50.

- [5] General Robert E. Lee to Adjutant General Samuel Cooper, September 3, 1862, in O.R., I, 12, pt. 2, 554; and Hennessy, Return to Bull Run, 92–95.

- [6] Major General John Pope to Brigadier General G. W. Cullum, Chief of Staff and Engineers., Headquarters of Army, January 27, 1863, New York, in O.R., I, 12, pt. 2, 36–37; John Pope, The Military Memoirs of General John Pope, Peter Cozzens and Robert I. Girardi, eds. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press), 148; and Hennessy, Return to Bull Run, 96–115.

- [7] Brigadier General John Gibbon to Captain R. Chandler, Assistant Adjutant General, King’s Division, September 3, 1862, Upton’s Hill, Va., in O.R., I, 12, pt. 2, 377; John Gibbon, Personal Recollections of the Civil War, Morningside Bookshop 1978 ed. (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1928), 51; and Hennessy, Return to Bull Run, 164–72.

- [8] Hennessy, Return to Bull Run, 167.

- [9] Hennessy, Return to Bull Run, 150–67.

- [10] Quoted in Hennessy, Return to Bull Run, 167; and Ibid., 150–67.

- [11] Brigadier General John Gibbon to Captain R. Chandler, Assistant Adjutant General, King’s Division, September 3, 1862, Upton Hill, Va., in O.R., I, 12, pt. 2, 377–8; Gibbon, Personal Recollections, 51–52; and Hennessy, Return to Bull Run, 164–72.

- [12] Brigadier General John Gibbon to Captain R. Chandler, Assistant Adjutant. General for King’s Division, September 3, 1862, Upton’s Hill, Va., in O.R., I, 12, pt. 2, 378; General Robert E. Lee to Adjutant . General Samuel Cooper, September 3, 1862, in O.R., I, 12, pt. 2, 555; John Pope, Letter from the Secretary of War, in Answer to Resolution of the House 18th Ultimo, Transmitting Copy of Report of Major General John Pope, H. Ex. Doc. 37-81, at 19 (1862); and Gibbon, Personal Recollections, 54.

- [13] General Robert E. Lee to Adjutant General Samuel Cooper, September 3, 1862, O.R., I, 12, pt. 2, 555–6; Charles King, “In Vindication of General Rufus King,” in Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, eds., Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Being for the Most Part Contributions by Union and Confederate Officers. Based Upon “The Century War Series”, 4 vols. (New York: The Century Co. 1884-1888), based on “The Century War Series” in The Century Magazine, November 1884 to November 1887, 2:495; and Pope, “The Second Battle of Bull Run,” in Battles and Leaders, 2:470–1.

- [14] General Robert E. Lee to Adjutant General Samuel Cooper, September 3, 1862, O.R., I, 12, pt. 2, 556–7; and Pope, “Second Battle of Bull Run,” in Battles and Leaders, 2:471–2.

- [15] General Robert E. Lee to Adjutant General Samuel Cooper, September 3, 1862, in O.R., I, 12, pt. 2, 556–7; and Pope, Letter of Secretary of War, H. Ex. Doc. 37-81, at 21–22.

- [16] General Robert E. Lee to Adjutant General Samuel Cooper, September 3, 1862, in O.R., I, 12, pt. 2, 556–7; and Pope, Letter of Secretary of War, H. Ex. Doc. 37-81, at 21–22.

- [17] Ibid.; General Robert E. Lee to Adjutant General Samuel Cooper, September 3, 1862 and Lieutenant General James Longstreet to Assistant Adjutant General R. H. Chilton, October 10, 1862, in O.R., I, 12, pt. 2, 557, 565; and Pope, Military Memoirs, 170.

- [18] Pope, Letter of Secretary of War, H. Ex. Doc. 37-81, at 22; and Pope, Military Memoirs, 170.

- [19] General Robert E. Lee to Adjutant General Samuel Cooper, September 3, 1862, and Lieutenant General James Longstreet to Assistant Adjutant General R. H. Chilton, October 10, 1862, in O.R., I, 12, pt. 2, 557, 565; Pope, Letter of Secretary of War, H. Ex. Doc. 37-81, at 23–24; John H. Worsham, “The Second Battle of Manassas: Account of it by One of Jackson’s Foot Cavalry; Pope’s Retreat to the Capitol,” in Southern Historical Society Papers, 32 (January–December 1904): 86; and Pope, Military Memoirs, 170.

- [20] General Robert E. Lee to Adjutant General Samuel Cooper, September 3, 1862, and Lieutenant General James Longstreet to Assistant Adjutant General R. H. Chilton, October 10, 1862, Winchester, Va., in O.R., I, 12, pt. 2, 557, 565; Pope, Letter of Secretary of War, H. Ex. Doc. 37-81, at 23–24; McClellan, “Report on Army of the Potomac,” Sec. of War, 38th Cong., 1st Sess., HED 15, ser. no. 1187, pp. 175–76; Pope, Military Memoirs, 170; and Hennessy, Return to Bull Run, 339–61.

- [21] Lieutenant General James Longstreet to Assistant Adjutant General R. H. Chilton, October 10, 1862, Winchester, Va., in O.R., I, 12, pt. 2, 565–6; and Hennessy, Return to Bull Run, 362–73.

- [22] Pope, “Second Battle of Bull Run,” in Battle and Leaders, 2:487–9; Lieutenant General James Longstreet to Assistant Adjutant General R. H. Chilton, October 10, 1862, Winchester, Va., in O.R., I, 12, pt. 2, 566; General Robert E. Lee to Adjutant General Samuel Cooper, September 3, 1862, in O.R., 1, 12, pt. 2, 557; Pope, Letter of Secretary of War, H. Ex. Doc. 37-81, at 24; and Hennessy, Return to Bull Run, 375–406.

- [23] Abial Edwards to Anna, September 7, 1862, Near Rockville, Md, Folder 3, Box 1, Abial Edwards Papers, Ridgway Hall, U.S. Army Heritage & Education Center; General Robert E. Lee to Adjutant General Samuel Cooper, September 3, 1862 and Lieutenant General James Longstreet to Adjutant General R. H. Chilton, October 10, 1862, in O.R., I, 12, pt. 2, 557–8, 566; Pope, Letter of Secretary of War, H. Ex. Doc. 37-81, at 24; and Hennessy, Return to Bull Run, 17, 407–41, 456-7.

- [24] General Robert E. Lee to Adjutant General Samuel Cooper, September 3, 1862, in O.R., I, 12, pt. 2, 558; Hennessy, Return to Bull Run, 17, 439–41, 456–7.

- [25] For more on Pope’s struggle to control the Army of Virginia, see John H. Matsui, The First Republican Army: The Army of Virginia and the Radicalization of the Civil War (Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 2016).

- [26] For more on Second Bull Run’s place as a precursor to the Battle of Antietam, see McPherson, Crossroads of Freedom.

If you can read only one book:

Hennessy, John J. Return to Bull Run: The Campaign and Battle of Second Manassas. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992.

Books:

Martin, David G. The Second Bull Run Campaign, July–August 1862. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Books, 1997.

Matsui, John H. The First Republican Army: The Army of Virginia and the Radicalization to the Civil War. Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 2016.

Patchan, Scott C. Second Manassas: Longstreet’s Attack and the Struggle for Chinn Ridge. Dulles, VA: Potomac Books, 2011.

Organizations:

Manassas National Battlefield Park

The National Park Service runs the Manassas National Battlefield Park located near Manassas Virginia. The Park is open daily from dawn to dusk. The Henry Hill Visitor Center is open daily 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. except Christmas Day and Thanksgiving Day. The Brawner Farm Interpretive Center is open daily from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. The Stone House is open on weekdays from 1:00 p.m. to 4:30 p.m. and on weekends from 10:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m.

Manassas Battlefield Trust

The Manassas Battlefield Trust is an active partner wit the Manassas National Battlefield Park, to preserve and protect the lands and resources associated with the First and Second Battles of Manassas. The Trust assists the Park’s mission to foster an understanding and appreciation of the battles and their significance through philanthropic support of opportunities for interpretation, education, enjoyment and inspiration.

Web Resources:

The American Battlefield Trust’s page on Second Manassas (Second Bull Run, Brawner’s Farm) contains a summary of the battle and links to a variety of resources and maps relating to the battle.

Other Sources:

Self-Guided Tour: The Battle of Second Manassas

Whitehorne, Joseph W. A. Self-Guided Tour: The Battle of Second Manassas. Fort McNair, Washington D.C.: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1990.