The Thirty-Fifth Star: The Civil War in West Virginia

by Richard H. Owens

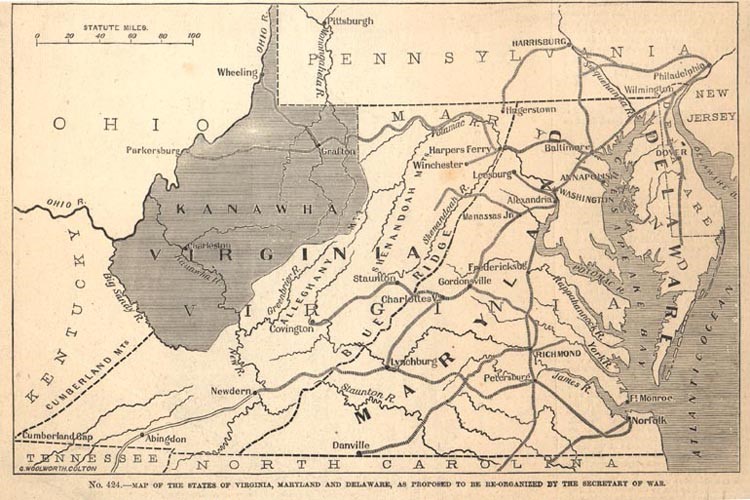

West Virginia was formed in 1861 by counties west of the Alleghenies whose inhabitants voted against secession. On June 20, 1863 West Virginia was admitted to the Union as the 35th state.

Political Background

Without question, the extent, scope, and importance of military engagements fought in the areas of the Old Dominion that became the state of West Virginia were far less significant than the political events in that region. No battle fought in what is now present-day West Virginia equaled in scope or import any of the more famous Civil War conflicts. Most encounters were more skirmishes rather than full-scale battles by Civil War standards. However, military events in the Civil War did have an important effect and parallel influence on politics and political alignments in the emerging anti-Virginia secessionist movement in the western counties of Virginia.

The Blue Ridge mountain range became a convenient eastern border for West Virginia. In addition to an historical and symbolic division between eastern and western Virginia, the line of the Blue Ridge also provided a defense against potential (albeit unlikely) Confederate invasion. That line also corresponded to the line of United States military influence and control, or the lack of Confederate military influence or interest, throughout most of the Civil War.

Most of the eastern and southern counties included in the new state of West Virginia did not support separate statehood. They were included for political, economic, and military purposes. The wishes of those citizens were largely disregarded. But they were under Federal military influence or lacked Confederate military pressure. Control (or lack thereof) of specific areas that became part of West Virginia was a significant factor.

On April 17, 1861, the state convention in Richmond declared for secession. Nearly all delegates from counties west of the Allegheny Mountains voted against secession, and most people and officials in that area refused directions from the secessionist Virginia state government. A subsequent (first) convention in Wheeling confirmed the displeasure of westerners at the decision driven in Richmond by the eastern, Tidewater, slaveholding aristocracy of the Old Dominion.

Following a Union victory led by Major General George Brinton McClellan over a small Confederate force at the Battle of Philippi on June 3, 1861 and McClellan’s subsequent occupation of northwestern Virginia, a second convention met in Wheeling between June 11 and June 25, 1861. Significantly, from that point forward, there was no Confederate military force or compulsion to prevent western Virginia’s separatist leaders from proceeding with their aspirations for their removal from Virginia. Union military occupation of much of western Virginia was thus a critical factor in subsequent political developments and the eventually successful moves to separate counties in the western region of Virginia and form a separate state.

Against that military backdrop, with Confederate forces driven from the state, delegates formed the Restored, or Reorganized, Government of Virginia in 1861. In a strictly political move rationalized under his war powers as commander in chief, President Abraham Lincoln immediately recognized the Restored Government as the legitimate government of Virginia. Military decisions and circumstances affirmed those political actions. Partly, the federal government was rewarding West Virginia’s loyalty to the Union. In part, it also was Lincoln’s Whig approach to the presidency, outside of his role as commander-in-chief. Throughout the West Virginia admissions process and drama, Lincoln essentially yielded the initiative and decisions to the Congress.

A referendum in the western counties in October 1861—without participation by the majority of Virginians living east of the Appalachians (who were by then part of the new Confederate States of America) approved statehood. On October 24, 1861, residents of thirty-nine counties in western Virginia approved the formation of a new Unionist state. The accuracy and legitimacy of those election results were questionable. Union troops were stationed at many of polls to prevent Confederate sympathizers from voting. Many opponents disputed the eventual vote tallies. It was hardly a free, open, democratic process. But it formed the basis for what followed.

At the Constitutional Convention in Wheeling from November 1861 to February 1862, delegates selected counties for inclusion in the new state of West Virginia. Many of those counties were under Union military control or devoid of any significant Confederate military presence or pressure. Most Shenandoah Valley counties were excluded from the initial list due to their control by Confederate troops and/or those areas having many local Confederate sympathizers. Again, military circumstances helped dictate political actions. All of present-day West Virginia's counties except Mineral, Grant, Lincoln, Summers, and Mingo, which were formed after statehood, became part of the new state. In the end, fifty counties were selected for the new state (which now has fifty-five).

The convention and subsequent Restored Government of Virginia represented and contained only several dozen western counties. And, it was not necessarily even representative of a significant majority of the people of those counties. The number of counties included in the separatist movement was itself subject to change. About thirty counties in the west had opposed secession. Thirty-nine counties voted to approve a new state. One of the most controversial decisions in creating West Virginia as a separate state involved the Eastern Panhandle counties. Those areas were strategically located and economically important. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, running through the Eastern Panhandle, was vital for the region’s economy, Union communications with the Midwest, federal troop movement, and the future of a separate state of West Virginia. Inclusion of these counties in West Virginia removed the railroad and those counties from Virginia’s jurisdiction and Confederate control. They were worthwhile targets for Federal troops, but without the western termini of those rail arteries, of much lesser import for Virginia or Confederate forces or action. Despite that, however, Lieutenant General Thomas Jonathan (Stonewall) Jackson still destroyed part of it.

The constitutional convention met, and its work was approved by referendum, in those same western counties only, not in the rest of Virginia, in April 1862. Congress approved statehood in December 1862, and it became effective on June 20, 1863. When Union troops later occupied parts of eastern Virginia such as Alexandria and Norfolk, these areas came under the jurisdiction of the Restored Government, but they were not included in West Virginia. With West Virginia statehood, the Restored Government relocated to Alexandria for the remainder of the war. What really mattered from a military, thus also a political, point of view was that areas under control of the Restored Government were also under control of Union armed forces.

Subsequent to withdrawal of Virginia’s military forces from the western regions of the Old Dominion after the Battle of Philippi and later Southern decisions not to contest an area of questionable military value to the Confederacy, formal military hostilities in the western counties of Virginia were minimal for the rest of the Civil War. However, there were brutal guerilla activities. Much of those focused on local issues and old regional hostilities rather than the larger military issues of the Civil War. Again, there were far fewer emancipationist or pro-Union interests in those areas than local, economic, traditional, and clan issues at stake in the western counties in the 1860’s.

After 1861, federal troops were stationed in critical areas throughout West Virginia—the areas of Virginia west of the Blue Ridge—largely to secure rail lines and other important features. During the Civil War, however, the Restored Government never effectively controlled more than twenty or twenty-five counties in West Virginia. Even where Union troops were present, maintaining law and order was inconsistent and precarious. Guerilla warfare was commonplace and brutal. But there was no more major fighting with Confederate regular forces. That state of affairs allowed political events leading to West Virginia statehood to proceed unimpeded by Virginian or Confederate military forces. It was aided by a federal troop presence that had visible effect on the direction in which those political events evolved in West Virginia in 1862 and 1863.

Significantly, all this occurred with Union forces in control of, or Confederate forces absent from, the areas in question. It also occurred without sanction, approval, or recognition from the constitutionally recognized government of Virginia, which—according to President Lincoln and Congress throughout the Civil War—never left the Union in the first place.

Nor were the citizens of Virginia ever asked directly through election or plebiscite to determine this crucial issue of severing a portion of their state and agreeing to its separate statehood. For example, the second sometimes called the “dismemberment” convention of 1861 was held only in the western counties. Neither the vast majority of the people or the elected (seceded) legislature, governor, or courts of the state of Virginia itself ever consented to separation of the western counties, let alone separate statehood for them.

The birth of the state of West Virginia occurred in meeting halls and conventions, not on the battlefields of the American Civil War. But Union military control of—or Confederate absence from—the western counties of the Old Dominion that became West Virginia formed a vital martial prerequisite and sustaining factor for the political actions that resulted in the establishment and maintenance of West Virginia statehood.

One might contend that the first fighting of the Civil War occurred in what became part of West Virginia, in Harper’s Ferry Virginia in October 1859 with the capture of John Brown. To many Southerners, John Brown’s raid on the Harper’s Ferry Arsenal was tantamount to an abolitionist (and thus in Southern minds to a Northern) declaration of war against slavery, the South, and the South’s way of life. In fact, following the Confederate shelling of Fort Sumter in April, 1861, it did not take long for fighting to erupt in the western counties of Virginia, the area that was soon to become known as West Virginia.

The Civil War officially began when Confederate artillery shelled the Union-held Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina on April 12, 1861. On April 17, 1861, Confederate leaders in Virginia decided to capture that same United States Armory and Arsenal at Harpers Ferry.

As southern militia marched toward Harpers Ferry, on the night of April 18, Union troops set fire to the armory and arsenal, preventing the weapons from falling into Confederate hands. Southern forces under Stonewall Jackson, however, took the town and established control over that part of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad leading into western Virginia. With its armory and arsenal, plus its location at the intersection of two major railroads, the Baltimore and Ohio and the Winchester and Potomac, Harpers Ferry was a key strategic stronghold. Because of that, Confederate control of Harper’s Ferry was only temporary. During the war, Harpers Ferry changed hands numerous times.

During the first weeks of the war, the Confederate government of Virginia assigned Colonel George Alexander Porterfield to recruit troops in western Virginia. In May and June 1861, Confederate forces advanced into western Virginia to impose control by the Richmond government and the Confederacy. They got no further than Philippi, due to bad roads and no local support.

When Union troops under General George McClellan advanced into the region, Porterfield withdrew his forces to Philippi. As McClellan approached, he sent Colonel Benjamin Franklin Kelley and the First Virginia Provisional Regiment (later renamed the First West Virginia Infantry) as an advance guard. On the morning of June 3, 1861, Kelley's troops attacked Porterfield's forces at Philippi, resulting in a Confederate retreat. This action—often dubbed “The Philippi Races”—was considered by some to be the first land battle of the Civil War, although in scope and import it paled in comparison with the first major land battle of the conflict at Bull Run in July, 1861.

Later, the Battle of Hoke's Run on July 2, 1861 in Berkeley County was part of the Manassas Campaign in which Stonewall Jackson successfully delayed a larger Union force. Although minimally involved in the fighting, as nominal commander of the Union forces in the area, George McClellan received most of the credit and acclaim for the minor Union victory at Philippi and related actions.

To prevent Union troops from advancing further up the Tygart Valley, reinforcements led by Brigadier General Robert Selden Garnett joined the retreating Confederates and established strongholds at Laurel Hill in Tucker County and Rich Mountain in Randolph County. In the Battle of Laurel Hill, July 7–11, 1861 in Barbour County, Union troops under Brigadier General Thomas Armstrong Morris routed Confederate troops in several days of skirmishing at Belington in a diversionary attack as the opening portion of the Battle of Rich Mountain. In the subsequent Battle of Rich Mountain on July 11, 1861 in Randolph County, Union Brigadier General William Starke Rosecrans won a decisive battle at Rich Mountain. Ironically, General George McClellan was credited with this victory and that led to his subsequent elevation to high command. On July 14, the retreating Confederates were routed at their position at Corrick's Ford.

This series of engagements resulted in Union control of northwest Virginia for virtually the remainder of the war. Union control of the east-west transportation routes made it difficult for Richmond to supply Confederate units in the western counties for the remainder of the war. This had two major results. First, there were few subsequent engagements between Union and Confederate forces in the northwestern counties of Virginia. And the absence of Confederate troops or influence helped to ensure the safety of West Virginia statehood meetings in Wheeling.

The Confederates were easily defeated in the northern part of present-day West Virginia. However, they produced a better effort in the Kanawha Valley, located in the central area of present day West Virginia. Among the factors aiding Confederate efforts there were greater distances from Union bases and the greater concentration of pro-Confederate and secessionist sentiment. Former Virginia governor Henry Alexander Wise, now a brigadier general, established his Southern forces at the mouth of Scary Creek in Putnam County. On July 16, Wise pushed back an attack by forces under Brigadier General Jacob Dolson Cox. All of this took part in the shadow of the far more significant Battle of First Bull Run (First Manassas) in northern Virginia in July 1861.

After the arrival of reinforcements, Cox's men drove Wise up the Kanawha Valley to Gauley Bridge and eventually into Greenbrier County. The North suffered a setback in August as General Rosecrans' forces were defeated at Kessler's Cross Lanes in Nicholas County while marching toward Gauley Bridge. Another former Virginia governor, Brigadier General John Buchanan Floyd, established his Confederate troops on a bluff at nearby Carnifex Ferry. Union troops attacked Floyd on September 10, 1861 and dislodged his forces.

A significant factor leading to the Southern defeat at Carnifex Ferry was a long-standing political rivalry between Wise and Floyd. The Battle of Carnifex Ferry led to Union control of the important Kanawha Valley in the early part of the war. Although Union casualties totaled 158 compared to 20 Confederate, the larger northern force drove both Floyd and Wise back into Greenbrier County. Obviously, these casualty figures paled beside those of First Bull Run (First Manassas) fought earlier in the month of July and even more so alongside the casualty figures of later Civil War battles. Still, in only a few months, Union forces had gained control of northwestern Virginia and the central area of the region in the Kanawha Valley, although the latter area was more vulnerable and did sway back and forth for much of the war.

In August, 1861, General Robert E. Lee, in his first assignment of the war, set up camp on Valley Mountain in Pocahontas County. Lee hoped to put more pressure on northwestern Virginia, but he overestimated Union strength arrayed at the Cheat Mountain Summit Fort and elected not to attack. Lee had nearly 15,000 men in the area, and perhaps could have re-taken much of northwestern Virginia had he pushed forward.

Again in October, Lee once more failed to attack Rosecrans' outnumbered force following the Battle at Carnifex Ferry. In stark contrast to Lee’s highly aggressive style later in the war, these early disappointments resulted in Lee’s reassignment to an administrative post in Richmond until the summer of 1862.

Three later and largely inconsequential battles in Pocahontas County need to be grouped: the Battle of Cheat Mountain on September 12–15, 1861, was the battle in which Robert E. Lee was defeated and thence recalled to administrative duties in Richmond. It was followed by an inconclusive fight at Greenbrier River on October 3, 1861, and six weeks later by the Battle of Camp Allegheny on December 13, 1861 in which both sides withdrew to winter camp following the repulse of a Union attack. After 1861, essentially the entire trans-Appalachian region of the Old Dominion was firmly under Union control, except for some of the easternmost counties.

Various skirmishes, guerilla activities and Confederate raids occurred in West Virginia during 1862 and 1863. But the essential fact was that the Confederacy pursued little to no resistance to or military action against the breakaway Restored Government in Wheeling and its efforts to achieve separation and statehood. Following the Union victory at the Battle of Droop Mountain on November 6, 1863 and subsequent to West Virginia’s admission to statehood, Confederate resistance in the western Virginia essentially ceased.

Northern control of western Virginia became stronger as the war went on. By 1865, it was essentially total, and fighting in the new state of West Virginia was almost nonexistent. By then, Confederate military support more often took the form of irregulars, troops never mustered into the Confederate service, or worse, guerillas bent more on plunder than military service. West Virginia's first governor, Arthur Boreman, considered these irregulars the most serious threat to the new state.

West Virginia's most famous band of these guerrillas was McNeill's Rangers, organized in Hardy County. During 1863 and 1864, they wreaked havoc on the B&O Railroad in the Eastern Panhandle, seizing numerous Union supplies. On February 21, 1865, the rangers executed their most daring raid when a small group of men rode into Cumberland, Maryland, kidnapped Union Major General George Crook and Brigadier General Benjamin Franklin Kelley, and delivered them to General Jubal Early. At the end of the war, McNeill's Rangers surrendered to Union troops under General Rutherford B. Hayes on May 8, 1865, one month after Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox.

Pro-Confederate guerrillas burned and plundered in some sections, and were not entirely suppressed until after the war ended. But while brutal and distressing, guerrilla warfare in West Virginia was hardly decisive.

Most Civil War era guerrilla activity in West Virginia took place in highly rural, nearly isolated areas where family and clan frictions and loyalties were greatest. Militarily, these encounters were of no serious consequence. In human terms, they were often brutal and inhumane in character and content. Geographically, they typically occurred, farther south and southwest as one traveled in the new state of West Virginia. In other words, there were far fewer pro-Union or emancipationist interests in those areas than local, economic, traditional, and clan issues at stake in the western counties in the 1860’s. Thus guerrilla warfare rather than traditional campaigns between soldiers of the blue and the gray occurred in these situations.

In West Virginia, there was relatively equal support for the northern and southern causes. This was reflected not only in military service but also various votes prior to and during the convention process that led to West Virginia statehood. Many of the votes were far closer than the proponents of separation and statehood wanted the public to know. But the numbers of troops engaged, and more specifically, the numbers of men enlisted in the conflict for either side, has been less easy to determine and remains a matter of dispute. Historians traditionally placed the number of Union troops enlisted in West Virginia at a much higher figure than Confederates. But more recent studies suggest there were almost as many southern troops as northern.

The real problems lie with scant or non-existent records, multiple registrations and musters, false identifications or enlistments, desertions, and the difficulty in counting accurately the casualties following any Civil War engagement, especially those conducted in remote or lightly administered areas such as was the case for much of West Virginia during the Civil War.

Traditional sources placed Union strength as high as 36,000 compared to only 7,000 to 10,000 Confederates. Recent studies have elevated the Southern number to over 20,000 and lowered the Union figure to about the same or maybe slightly higher (low to mid- twenty thousands). Of course, the numbers fluctuated throughout the war, and were typically higher in the earlier years of the conflict.

Maximum numbers for either side were likely around 28,000 each, and usually were less than that, closer to twenty thousand or so each, with the counts diminishing as the conflict neared its end. It is impossible to separate reenlistments, multiple enlistments and other variables to obtain an exact count. By Civil War standards, however, the number of men from either side who took part in actions in present West Virginia is quite small compared to the numbers who saw combat in other theatres of the conflict.

Part of the problem with early studies is they ignored numerous southern sympathizers who fought in militias or as irregulars. Many of these men fought seasonally or only when local action spurred them to service. Most importantly, numbers did not always translate to effective or concentrated strength. In none of the engagements fought in West Virginia was the issue of numbers a crucial factor in determining the outcome of a specific engagement. While men from West Virginia served on both sides in the war, those in Confederate service were organized in "Virginia" regiments. Those in Union service were designated as "West Virginia" regiments. Several Union "Virginia" regiments were re-designated upon West Virginia’s admission to statehood.

Both sides experienced problems with recruitment in western Virginia. On May 30, 1861, Brigadier General George B. McClellan wrote to President Lincoln in May 1861 of his optimism for recruiting volunteers in the region. However, by late summer he indicated frustration and pessimism to Governor Pierpont of the Restored Government of Virginia regarding prospects for raising more troops in West Virginia. That same summer, the Wellsburg Herald (in the northern panhandle region of West Virginia, just north of Wheeling, the center of separatist action) editorialized about a mere four incomplete West Virginia regiments in the field, and only one of those from the Panhandle.

Confederate authorities experienced similar problems at the beginning of the war. In May 1861, Confederate Colonel George Porterfield sought volunteers in Grafton volunteers, but reported slow enlistment. Confederate efforts were greatly undercut by lack of support from Richmond. That government did not send enough guns or other supplies. Porterfield eventually turned away hundreds of volunteers due to lack of equipment. General Henry A. Wise also complained of poor response to recruitment efforts in the Kanawha valley, although he eventually assembled about 4,000 men for "Wise's Legion."

In April 1862 the Confederate government instituted a military draft, and nearly a year later the U.S. government did the same. The Confederate draft was not generally effective in West Virginia due to the breakdown of Virginia state government in the western counties and Union occupation of the western counties, although some Confederate conscription did occur in the southern region of West Virginia.

The Wheeling government asked for an exemption to the Federal draft. The basis for the request was that they had exceeded their quotas under previous calls. An exemption was granted for 1864, but in 1865 a new demand was made for troops, which Governor Boreman struggled to fill. In some counties, ex-Confederates suddenly found themselves enrolled in the U.S. Army. Rapid Federal conquest of northern West Virginia caught some Southern sympathizers behind Union lines. In some cases, these men subsequently were drafted or mustered into Union units.

There has never been an official count of Confederates who saw service in West Virginia. Early estimates were about 7,000. Later studies saw the number increase into the 12-15,000 range, then rise again to about 18,000. In 1864, the Confederate Department of Western Virginia cited a figure of 18,642. According to the Provost Marshal General of the United States, the official number of Union soldiers from West Virginia was 31,884. However, towever, tHowever, those numbers apparently include re-enlistment figures as well as out-of-state soldiers who enlisted in West Virginia regiments. Total numbers are estimates, but typically run in the 18,000 to 32,000 range for each side.

With the defeat of Confederate forces at the Battle of Philippi and the Battle of Cheat Mountain local supporters of Richmond were left to their own devices. Many guerrilla units originated in the pre-war militia, and these were designated Virginia State Rangers and starting in June, 1862, these were incorporated into Virginia State Line regiments. By March, 1863, however, many were enlisted in the regular Confederate army.

There were others though who operated without sanction of the Richmond government, some fighting on behalf of the Confederacy, while others were nothing more than bandits who preyed on Union and Confederate alike. Union authorities began to organize their own guerrilla bands, the most famous of which was the "Snake Hunters", headed by Captain John P. Baggs. They patrolled Wirt and Calhoun counties through the winter of 1861-62 and captured scores of Moccasin Rangers, whom they sent as prisoners to Wheeling.

The fight against the rebel guerrillas took a new turn under General John C. Frémont and Colonel George Crook, who had spent his pre-war career as an "Indian fighter" in the Pacific Northwest. Colonel Crook took command of the 36th Ohio Infantry, centered in Summersville, Nicholas County. He trained them in guerrilla tactics and adopted a no-risoners policy.

On January 1, 1862, Crook led his men on an expedition north to Sutton, Braxton County, where he believed Confederate forces were located. None was found, but his troops encountered heavy guerrilla resistance and responded by burning houses and towns along the line of march. But by August, 1862, Unionist efforts were severely hampered with the withdrawal of troops to eastern Virginia.

In this vacuum, General William W. Loring, C.S.A, recaptured the Kanawha valley, General Albert Gallatin Jenkins, C.S.A., moved his forces through central West Virginia, capturing many supplies and prisoners. Confederate recruitment increased, with General Loring opening recruitment offices as far north as Ripley.

Responding to Confederate raids, Brigadier General Robert Huston Milroy demanded cash reparations and proceeded to assess fines against Tucker county citizens, whether they were guilty or not of harboring Confederate sympathizers. He also threatened them with the gallows or house-burning. Jefferson Davis and Confederate authorities lodged formal complaints with General Henry Wager Halleck in Washington, who censured General Milroy. However, Milroy argued in defense of his policy and was allowed to proceed.

By early 1863 Union efforts in West Virginia were going badly. Unionists were losing confidence in the Wheeling government to protect them, and with the approaching dismemberment of Virginia into two states guerrilla activity increased in an effort to prevent organization of county governments. By 1864 some stability had been achieved in some central counties, but guerrilla activity was never effectively countered. Union forces that were needed elsewhere were tied down in what many soldiers considered a backwater of the war. But Federal forces could not afford to ignore any rebel territory, particularly one so close to the Ohio River.

As late as January, 1865, Governor Arthur I. Boreman complained of large scale guerrilla activity as far north as Harrison and Marion counties. One of the last, brazen acts of the guerrilla war was the McNeill's Rangers (of Hardy County) kidnapping of Generals George Crook and Benjamin Kelley from behind Union lines discussed above. The Confederate surrender at Appomattox finally brought an end to guerrilla war in West Virginia.

In many ways, the military aspects of the U.S. Civil War in West Virginia were constantly overshadowed in scope by battles elsewhere and in political significance by the movement for separation and statehood. Yet ultimately, the most important and lasting development in West Virginia in the Civil War era was indeed the separation of the western counties from Virginia and their incorporation into the thirty-fifth state of the Union.

West Virginia entered the Union under unconstitutional circumstances. Its severance from Virginia and reincorporation as a new state in 1863 occurred outside the bounds of constitutional legality. West Virginia statehood resulted from a unique but convoluted series of developments by which the United States government, while pledged to prevent the secession of eleven states from the Union, nevertheless condoned and ultimately affirmed secession of fifty counties from one of those states without the permission of the original state, Virginia.

President Lincoln abetted the process under his war powers, and the federal government, acting through Congress, conveniently employed the necessary political fig leafs. West Virginia statehood was the only time in American history that a state was created and admitted to the Union without following the prescribed constitutional process. Previously, Vermont (claimed by New York and New Hampshire) and Maine (part of Massachusetts) became states with the consent of the states that claimed those areas. Even Lincoln’s own Attorney General, Edward Bates, declared that the process by which West Virginia was admitted was unconstitutional.

Sectional differences had existed between western and eastern Virginia from the early seventeenth century. Those political, economic, and cultural differences became more acute as greater numbers of new settlers moved west of the Appalachians. Physical, economic, political, and cultural preferences between the two areas of the state continued to diverge throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. There were also religious differences, but by far, economic and political issues separated east from west in the Old Dominion.

Slavery was and remained deeply rooted in the eastern areas of Virginia, especially in the coastal and tidewater regions. The centrality of slavery to the political, economic, and social life of eastern Virginia marked the most significant difference and point of political divergence with the western region of the state. Yet it was less slavery per se than the political and economic issues resulting from it that created substantive differences and friction between eastern and western Virginia (as well as the northern and southern portions of western Virginia).

Several plans for division or dismemberment of Virginia actually appeared in the decades prior to Virginia’s act of secession in 1861. But white Easterners—richer and more powerful, but fewer than western Virginians—controlled the state, its key offices, its institutions, its policies, and its political power. Additionally, those western Virginians were developing economically along different lines than the plantation and slavery dominated Tidewater. And, by the 1850’s, they were becoming more politically aggressive.

Typical of the ‘haves,’ Eastern leaders were committed to the status quo. That included Eastern preeminence in state politics, including control of the state legislature and most crucial state offices. Westerners saw the east declining economically, with the waning of plantation agriculture and transformation of slavery into an industry of human propagation producing slaves for export to the burgeoning agricultural states to the southwest. But Easterners had the political leverage and power, and they were unwilling to grant many concessions to the non-slaveholding western counties. Most western grievances had nothing to do with anti-slavery principles or humanitarian concerns related to slavery. Rather, their issues centered on Eastern legislative representation (disproportionately based on representation formulae that included counting slaves in the population for purposes of apportionment) and the share of taxes and state revenues allocated between east and west. Thus, key issues were related to slavery, but much more in the way slavery impacted the political priorities, economies, and power structures of the state, not a concern for the slaves themselves or the institution per se.

Following the initial secession of seven states between December 1860 and February 1861, and the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter in April, events moved quickly. On April 17, 1861, delegates in Richmond passed an Ordinance of Secession for Virginia by a vote of 88 to 55. Western delegates withdrew from the convention, returned to western Virginia, and began planning opposition to the ordinance and secession, which was scheduled for statewide vote by the citizens of the state on May 23, 1861. Throughout western Virginia, citizens met in support of or in opposition to actions taken by their delegates at the Richmond Convention. The majority of westerners opposed the Ordinance of Secession, but that varied from county to county.

On May 13, 1861, delegates from twenty-seven western Virginia counties duly assembled at Washington Hall in Wheeling to consider responsive action to Virginia’s Ordinance of Secession, which was approved by the voters of the Commonwealth on May 23, 1861. One option suggested immediately was secession of the western counties from Virginia, a course that ultimately developed and succeeded. Virginia’s secession from the Union had provided a pretext. However, the rationale had been building for decades. The May 23, 1861 vote for Virginia’s secession from the Union only served to solidify preference for separation among citizens of the western counties.

Following and precipitated by ratification of Virginia’s Ordinance of Secession, delegates from western counties gathered at Washington Hall (now called Independence Hall) in Wheeling on June 11, 1861, to determine a course of action for northwestern Virginia. Through all these deliberations of 1861-1863, while all of the officials and delegates considering separation from the rest of Virginia were from the western counties in question, the majority, including those with the most significant roles and influence, were from the northern panhandle region.

On June 19, 1861, members of the convention voted unanimously in favor of a proposed ordinance for reorganizing the government of Virginia. This took place despite the fact that the duly constituted government of Virginia remained in office, in control of the apparatus of the state, physically unhampered, and legally uncontested in Richmond. On June 20, maintaining the fiction that the real government of the Commonwealth of Virginia had simply ceased to exist—when in reality everyone knew that it was alive and well in Richmond—delegates selected officials to fill the offices of the Restored Government of Virginia. That was the government of West Virginia that ultimately sought and was granted separate statehood. The Wheeling Convention adopted the separation and statehood recommendations by a vote of fifty to twenty-eight, about two to one, but far from unanimous. Affirmation by voters in all counties of separation and separate statehood was scheduled for October 24, 1861.

On October 24, 1861, voters from the counties of the proposed new state went to the polls. Considering the importance of the vote, turnout was surprisingly low. Moreover, the vote occurred in only forty one, not forty six, counties. Only about thirty-seven percent of eligible voters chose to cast ballots. Perhaps they recognized a fait accompli; perhaps they were ambivalent; perhaps they opposed separation from Virginia but were intimidated when it came to standing publicly against the proposal. Still, given its import, participation was low. When the ballots were counted, 18,408 votes were cast in favor of the new state, while only 781 were opposed. Voters also elected delegates to represent them in a new constitutional convention to design the framework of government for the new state.

On November 26, 1861, delegates met in Wheeling to create a Constitution for the new state. This was the (West Virginia) Constitutional Convention. Issues included the name of the new state, boundaries, and the issue of slavery. A number of delegates spoke strongly either in favor of or against the inclusion of the word “Virginia” in the new state name, but “West Virginia” eventually was selected.

Of much greater import, the issue of slavery constantly hung over the convention. While some pressed for gradual emancipation, they were unable to convince a majority of delegates to include that option in the new state constitution. The final document simply stated, “No slave shall be brought, or free person of color be permitted to come, into this State for permanent residence.” That was hardly a ringing endorsement of emancipation or racial equality, in contrast to the majority of Congressional Republicans or the opinion of President Lincoln. Although the convention proposed that neither slaves nor free blacks be allowed, the rhetoric and subsequent mythology underlying the case for West Virginia’s separation from its parent Commonwealth included reference to the region’s opposition to slavery–an institution so prevalent in the eastern areas of the state–and the Tidewater politicians who so strongly upheld the “peculiar institution” in Virginia. Ambivalence or opposition to emancipation or racial equality did not prove to be obstacles to eventual admission of West Virginia to the Union.[1]

Meanwhile, throughout 1861 and thereafter, Union military occupation of much of western Virginia was a critical factor in subsequent political developments and the eventually successful moves to separate counties in the western region of Virginia and form a separate state. There was no Confederate military force or compulsion to prevent western Virginia’s separatist leaders from proceeding with their aspirations for their removal from Virginia. On May 6, 1862, the General Assembly of the Reorganized Government of Virginia was convened by Governor Francis Pierpont. One week later, that General Assembly passed an act granting permission for the western counties assembled in Wheeling to create the new state. This proved to be the ‘legal’ basis for separating the western counties from Virginia with its ‘assent.’

On June 23, 1862, the Senate Committee on Territories reported the bill to the U.S. Senate. When the bill was introduced, abolitionists called for an amendment requiring emancipation of all slaves in West Virginia on July 4, 1863. This proposal was defeated. Eventually, the Senate agreed on a compromise. A substitute proposal called for admission of West Virginia upon approval of gradual emancipation by its constitutional convention (in Wheeling). This Willey Amendment, which provided for gradual emancipation, passed; and on July 14, 1862, the West Virginia statehood bill also passed the U.S. Senate by a vote of 23-17, with eight abstentions. Had seven of the eight abstainers voted against admission, the bill would have been defeated.

Debate in the U.S. House of Representatives over admission of West Virginia as a state also was contentious. However, on December 10, 1862, the U.S. House passed the West Virginia statehood bill by a vote of 96 to 55. The two to one majority was substantial but far from overwhelming. Clearly, many in the North had reservations, but at that point, West Virginia was on the verge of attaining its rogue statehood.

When President Lincoln received the West Virginia statehood bill on December 15, 1862, he was deeply distressed. He asked the six members of his cabinet for written opinions on the constitutionality and expediency of admitting West Virginia to the Union. They divided evenly. Lincoln had supported creation of the Reorganized Government of Virginia, but recognized that the West Virginia statehood bill was being forced upon him by Radical Republicans in their effort to use the war and West Virginia statehood to weaken Virginia and expedite an end to slavery in the United States. Despite his reservations, on December 31, 1862, President Lincoln signed the West Virginia statehood bill. It was a matter of political expediency.

The Congressional statehood bill required West Virginia to submit its revised constitution containing the Willey Amendment to the Constitutional Convention in Wheeling for approval. Delegates reconvened in Wheeling on February 12, 1863. After tabling a committee resolution for compensation, delegates unanimously approved the Wiley Amendment and the full revised state constitution for West Virginia on February 17, 1863. Voters in the emerging new state ratified the revised constitution for the state of West Virginia on March 26, 1863 by a lopsided vote of 28,321 to 572.

Upon receiving the results, President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation on April 20, 1863, declaring that in sixty days, West Virginia would become the thirty fifth state of the Union. It did so on June 20, 1863, becoming the thirty-fifth state.

West Virginia was formed in the cauldron of the Civil War. In 1863, the new state and its people reflected the opinions and principles of that still-divided nation. But the war had given birth to the Mountain State. Perhaps for no other state in the United States was the American Civil War such a crucial and seminal event.

- [1] First West Virginia Constitution, Article XI Section 7, http://www.wvculture.org/history/statehood/constitution.html accessed May 14, 2014.

If you can read only one book:

Owens, Dr. Richard H. Rogue State: The Unconstitutional Process of Establishing West Virginia Statehood. Lanham, MD: University Press of America/Rowan & Littlefield, 2013.

Books:

Rice, Otis & Stephen Brown. West Virginia: A History. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1993.

Snell, Mark. West Virginia and the Civil War: Mountaineers Are Always Free. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2011.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.