Women and Soldiers' Aid Societies

by Beverly C. Tomek

In both the North and South women created support groups generally called Soldiers’ Aid Societies or Ladies’ Aid Societies. Over three months before the first shots rang out at Fort Sumter, southern women came together through their existing organizations to roll bandages, and a month after the fighting began, they were making cartridges and preparing sandbags for military use. Two days after the fighting began, northern women joined the war efforts as well. Their organized efforts began when the women of Bridgeport, Connecticut founded the first official soldiers’ aid society on April 15, 1861. In the North in the early years of the war, black women joined white women’s societies, but once black men were allowed to enlist, black women began to form societies of their own to focus specifically on the needs of black men. In the North women set up as many as 20,000 aid organizations. In the South, where record keeping was poor, nearly every town and village had a society so there were likely as many such organization as in the North. The function of the societies was similar in both regions. First and foremost was to gather supplies and get them to the soldiers—food, tents, clothing, blankets, bandages and in the South cartridges. These were made or purchased using funds from donations. The societies also supported soldiers’ families on the home front, donating food and necessities to poorer families. Donations were raised by social events such as concerts, tableaux, dinners, and dances. While all these activities fitted the traditional domestic sphere in which women of the time were expected to operate, the societies expanded women’s roles from supplying and supporting soldiers to helping to heal them. In particular, women began to take on a role in nursing, until that time an exclusively male preserve. In the North this change led eventually to the creation of the US Sanitary Commission and the Central Association for Relief which actively recruited and trained women to become nurses. This development was not as extensive in the South which did not create such organizations, but which did see women entering into nursing as well. In addition, in the North many aid societies also made common cause with abolitionist organizations pushing for the abolition of slavery as a war aim. After the war the North and South continued on divergent courses. In the North, many of the societies transformed into mutual relief agencies that worked to help veterans and their families apply for pensions and readjust to civilian life. They helped provide for disabled soldiers and their families in many cases, especially when war-related disabilities prevented the soldiers from returning to their jobs. Many of the women who had served in the aid societies went on to join suffrage societies and using their legacy of sacrifice and leadership to continue to leave the domestic sphere and to engage in politics. In the South women largely returned to the traditional domestic sphere and transformed their aid societies into memorial associations, creating Confederate cemeteries, erecting monuments and salving the emotional wounds of the men who had suffered defeat. Historians disagree on the extent to which women’s efforts during the Civil War changed their lives in the long run. After the war, most willingly returned to their domestic sphere, if they had actually left it at all, but on both sides, women had honed organization and political skills. They had displayed patriotism and loyalty and expected to be recognized for it. Whether they stepped out of the domestic sphere or not, returned to it or not it is clear that women had done things they had never done before and that they were not going to go backwards from that.

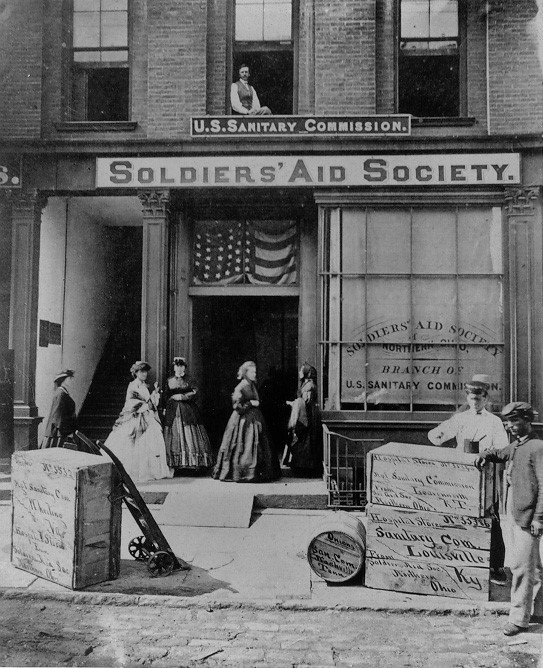

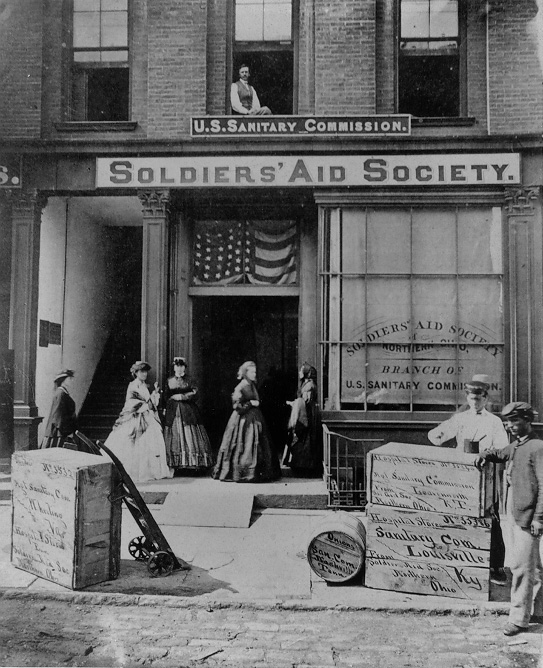

Women members of the Soldiers’ Aid Society of the U.S. Sanitary Commission stand in front of the Society’s offices on Bank (West 6th Street) in 1865.

Photograph Courtesy of: The Western Reserve Historical Society at Case Western Reserve University

As the train arrived in Philadelphia in early September of 1862, Katherine Wharton looked out the window upon familiar scenes. This time, however, the sights of the city reminded her of the grim realities of war. Independence Square, usually a landmark dedicated to American patriotism and unity, was on this occasion serving as a military campsite for Union soldiers who would soon be fighting other Americans on battlefields nearby and much farther to the South.

Independence Square, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania c1860-1870. Photograph Courtesy of The Library Company of Philadelphia. http://librarycompany.org/ , accessed June 10, 2019.

On this day they were working to recruit the men and boys of Philadelphia to join them on the front lines.

As she watched the activity, Wharton, who had been married a mere two and a half years when the war broke out, must have begun to wonder what she could do to play an important part in helping the Union effort. She wrote little about her husband in her journal, so it remains unclear whether he had enlisted. Perhaps her silence reflects the fear and anxiety of a woman whose husband is off fighting, or perhaps it reflects the shame of a woman whose husband stayed behind in safety while others risked their lives for the cause. Either way, her silence gives no clue as to her husband’s status, but her entries do speak volumes about her state of mind and her own desire to participate.

Whether the sight of the soldiers in Independence Square moved her, or whether some other motivating factor led her to action, she began rolling bandages for local hospitals. In 1863 she joined the Soldiers’ Relief Association and, along with other middle-class women like herself, funneled her energies toward contributing to the war effort in any way she could. She recorded in her diary her desperate need to “get some of this weight off my heart.”[1] Wharton joined the effort later than many women but once she decided to participate, she became part of a vital network whose efforts were indispensable on both sides of the war.

THE EMERGENCE OF SOLDIERS’ AND WOMEN’S AID SOCIETIES

As tensions between the sections reached the boiling point and men began to prepare for war in 1861, women rushed to make preparations of their own, and their efforts would prove essential both in the Union and in the Confederacy. In both regions women would create support groups that are sometimes called Soldiers’ Aid Societies and sometimes called Ladies’ Aid Societies. In the North, women had been working for decades to reform society and one of the main aims had been the abolition of slavery. Many of these women saw the impending war as a means to finally achieve this goal, and the last thing they were willing to do was abandon the cause at such a decisive moment. Other women of the North had not been particularly active in the abolition cause, but they wanted to do what they could to help their husbands, fathers, brothers, and other loved ones preserve the Union.

Southern women had also worked long and hard to defend their region’s way of life, including the human bondage that underlaid the South’s social and economic structures. Many of these women turned to existing mutual aid societies to begin planning for their important role in the Civil War, while others began to form new organizations specifically for the purpose of war aid. Over three months before the first shots rang out at Fort Sumter, southern women came together through their existing organizations to roll bandages, and a month after the fighting began they were making cartridges and preparing sandbags for military use.[2]

Two days after the fighting began, northern women joined the war efforts as well. Their organized efforts began when the women of Bridgeport, Connecticut founded the first official soldiers’ aid society on April 15, 1861. The women of Hartford followed suit in May by creating their own society and assigning members to collect goods and funds for specific Connecticut regiments and working with doctors on the frontlines by filling their requests for specific supplies.[3] Ohio also had an active aid society network, beginning with the efforts of Cleveland women, who formed the Cleveland Ladies’ Aid Society just five days after President Abraham Lincoln called for troops. Created by women from various churches in the city, this group began its work by hosting a blanket drive to collect quilts and blankets for troops being mustered at Camp Taylor in Cleveland. Six months later they joined efforts with other similar groups to form the Soldiers’ Aid Society of Northern Ohio. This group relied on donations to fund their efforts to care for sick and wounded soldiers by providing an ambulance service, hospital care, and essential medical supplies. They eventually established a depot hospital in Cleveland. Women in Columbus undertook similar work, creating a 45-bed hospital in 1863 and raising nearly $75,000 in cash for the cause.[4]

Other cities throughout the North would soon follow. In Troy, New York, Emma Willard called for the establishment of a soldiers’ aid society instantly upon hearing news that the war had begun. Serving as president of the society, she led an effort to secure a government contract to make clothing for the soldiers, employing their wives to fulfill the orders. This initiative not only provided clothing for the soldiers but also provided income for their families during their absence.[5] Philadelphia, a city long known for its reform societies, hosted a number of aid societies during the war, including the Philadelphia Ladies’ Aid Society and the Spring Garden Hospital Aid Society.[6]

Ladies and soldiers’ aid societies also dotted the Midwest. In St. Louis, Jessie Benton Frémont, the wife of General John C. Frémont and daughter of Senator Thomas Hart Benton, organized The Ladies Union Aid Society to care for sick and wounded soldiers and provide for their burial needs. Cordelia Adelaide Perrine Harvey, the widow of Wisconsin governor Louis Powell Harvey, led similar efforts in her state, and in Illinois women assembled in August of 1861 to form the Ladies’ Springfield Soldiers’ Aid Society for similar purposes. Iowa women, led by Annie Turner Wittenmyer from Keokuk, formed an active system of aid societies across the state.[7]

Living in a border state that had conflicted loyalties, the women in Maryland were torn, with some creating societies to support Union soldiers and others creating societies to support Confederate soldiers. Men in Baltimore created the Union Relief Association in June of 1861 and remained nominally in charge even though women inspired the effort and took the lead in the group’s work, which included handing out food and cold drinking water to regiments marching between railroad stations in the city. Their aid work included feeding captured Confederate prisoners of war and refugees from the South.[8]

In the early years of the war, black women joined white women’s societies, but once black men were allowed to enlist, black women began to form societies of their own to focus specifically on the needs of black men. Generally, the women who participated were drawn from the highest strata of their communities, but given the barriers black Americans faced, they were still generally less well-off than their white counterparts. As a result, their societies usually had less money available and members usually had less time to dedicate to the cause than white members. Even so, they created a number of independent organizations to serve the 186,000 black soldiers and 30,000 black sailors who participated in the Civil War. Given the city’s large black population, it should come as no surprise that a large number of these organizations, including the Colored Women’s Sanitary Commission, the Ladies’ Sanitary Association of St. Thomas Episcopal Church, the Soldiers’ Relief Association (which met at Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church), and the Ladies’ Union Association, were located in Philadelphia.[9] Other societies included the Ladies’ Soldier’s Aid Association of Carlisle, Pennsylvania; similar organizations in Norfolk and Portsmouth, Virginia; Wilmington, Delaware; and a Washington, D.C. society that enjoyed the support of well-known black abolitionists, Harriet Ann Jacobs and Sojourner Truth. Northern Ohio was home to the Colored Ladies Auxiliary of the Soldier’s Aid Society, and Louisville, Kentucky; Lawrence, Kansas; and Chicago also had their own black-led societies. Further north, black women founded societies in Hartford, New Haven, and Bridgeport, Connecticut and in the South they created societies in Newbern, North Carolina and Charleston, South Carolina. These societies raised money to buy supplies for black troops but also worked to provide for the needs of former slaves, creating schools for freed children, hospitals for freed people, and a host of societies aimed at taking care of the health and welfare of the recently emancipated.[10]

By the end of the summer of 1861, women throughout the divided country had come together to form soldiers’ aid societies all over both regions. During the course of the war they would purchase over ninety percent of the medicines used by army surgeons, produce or pay for perishable goods such as vegetables and meats, collect and distribute necessities such as tents and cots, and make or buy essential items such as blankets, pillows, pillow cases, sheets, towels, quilts, shirts, socks, canned fruits, jellies, and wine for soldiers. They also collected bandages and lint, which surgeons on the battlefields and in the makeshift hospitals used to pack wounds. Collectively the women raised almost five million dollars in cash and fifteen million dollars’ worth of goods. In the North alone, women set up into as many as 20,000 aid organizations. According to historian Rachel Seidman, the women’s groups “ranged greatly in size and organization,” including “small, informal gatherings of women who came together in the first heady weeks of war to can a few peaches and knit some socks before fading away” as well as “grand institutions like the Ladies’ Aid Society of Philadelphia, which by 1863 estimated it had received and distributed more than $60,000 worth of goods.”[11]

In the Confederacy, women scrambled to make up for their region’s lack of basic industry and infrastructure. While record keeping was less centralized in the South, leaving less certainty as to the exact number of societies that emerged in the region, one estimate has 1,000 in the South with at least 100 each in South Carolina and Alabama. Another study places 150 in South Carolina within the first few weeks of the war. Historian Anne Firor Scott estimates that not long into the conflict “nearly every town and village in the Confederacy had its society with the result that, in proportion to population, there were at least as many women’s groups at work as in the North.” What is certain is that almost immediately the region’s benevolent societies, missionary societies, and Sunday schools transformed into soldiers’ aid societies. Women from different sects and congregations joined forces and converted their churches into storage facilities and small-scale factories where they gathered to sew clothing and bedding and knit socks. One group managed to produce 2,320 garments in three months.[12]

In addition to helping the men and the war effort, these societies aided soldiers’ families on the home front and gave the middle-class women who ran them a new sense of purpose and importance, as well as a chance to socialize and give each other much needed moral support. In many ways, wartime activity highlighted the class divisions among women. Not only did the upper and middle-class women of the aid societies provide food and firewood for poorer families while their men were away, they also helped illiterate soldiers and their wives communicate by writing and reading letters for them. The women worked with a sense of shared suffering and sacrifice, but the reality was that poorer women suffered and sacrificed in much greater proportion. As the women of the aid societies learned to do without luxuries such as new dresses and fancy items, the poorer women and their children often had to do without basic necessities such as food. The societies allowed upper class women to help alleviate the suffering of the poor at least in some measure while also creating support networks that gave them an outlet for their own frustrations. According to Seidman, their wartime efforts allowed women to concentrate productive energy in a way that made them feel they were essential to the war effort while also providing emotional support to members. “As members gathered food and clothing and secured cash donations,” she argues, “they gained access to the information they craved, and they honed their organizational and political skills.”[13]

FUNCTIONS OF SOLDIERS’ AND WOMEN’S AID SOCIETIES

Regardless of the region, soldiers’ and women’s aid societies performed similar functions. According to Scott, “despite the vast difference in the situation each confronted, women on both sides of the conflict approached their work in ways that were remarkably similar.”[14] Of course, the first order of business was to gather supplies and get them to the front lines. In many cases the women assembled in private homes or borrowed community facilities to make goods that soldiers needed. This led to many sewing and quilting bees where they produced clothing and bedding for the men. They also came together to cook and preserve food that they could share with soldiers as well as with the families that soldiers left behind. In the South, women also made cartridges for the soldiers’ firearms.

Many of the raw materials and food products were donated and the women developed strong management skills as they kept up with incoming donations and outgoing shipments of finished supplies. In more rural areas, especially in the South and Midwest, women on farms grew the food and then they and their associates in town would prepare and preserve it. To procure supplies that were not donated, women had to become adept fundraisers. They did this by sponsoring concerts, tableaux, dinners, dances, and other social events.[15] These events not only raised money but also provided the communities diversion, entertainment, and a chance to come together to provide much needed emotional support for those left on the home front while their loved ones risked their lives on the battlefields. The women also had to learn the art of negotiation as they procured needed supplies and arranged for finished goods to be delivered to the soldiers. In many communities they were able to work out special deals with railroad companies to deliver the goods for free.

Social events were only one of the many ways women in both regions upheld community morale throughout the war. Given the prevailing gender stereotypes of the time, which held that women were the delicate and nurturing sex and thus belonged in the domestic sphere, women were expected to provide emotional support to the soldiers as well as to those who remained on the home front. Despite these stereotypes they were also expected to engage in self-denial and self-sacrifice, showing a strength that belied assumptions of delicacy.

Ignoring their own fears and concerns, women encouraged their male family members to enlist in the war and stay in the fight even as they faced deprivation and rough circumstances at home due to the absence of those male figures. They also encouraged the men to contribute much-needed resources to the military, even when they needed those resources on the home front, and when the men did so, the women were left to figure out how to make do. Just as importantly, the women were tasked with providing emotional support by remaining stoic and hiding their own fears and soothing the men’s concerns and fears through letters that remained positive and neglected to mention the hardships and problems at home. They were “expected to endure soldiers’ leave-taking with smiles, kisses, and approval rather than with tears, fears, and doubts.”[16] In the Confederacy, even more than in the Union, women’s main role was to sustain the men’s morale and cheer and encourage them to keep fighting. To provide tangible evidence of their support, they presented the men of their local companies with uniforms and flags to remind them of the importance of their cause. All of these activities were readily accepted as part of the women’s traditional role because they comported well with stereotypical notions of what should be included in women’s sphere of influence.

One very important function of women’s aid societies expanded that sphere, however, and caused a great deal of controversy. On the surface it might seem that nursing would fit into the domestic realm, but traditional stereotypes and prejudices dictated against women taking on such a profession, given that it often required that they see “intimate” parts of the male body and perform strenuous and indelicate physical work. Not long after the fighting began, however, exigencies of the war led people in both regions to reconsider the qualms they had at the idea of female nurses. According to historian Drew Gilpin Faust, “the unanticipated demands of an ever-expanding war soon began to undermine abstract ideological commitments to notions of appropriate female roles.”[17]

Women began serving as nurses in the South just a few months into the war as unexpected numbers of wounded and sick soldiers began to overwhelm existing resources as early as the summer of 1861. The women, who had already been organizing and working in aid societies to sew and cook, shifted their focus to nurturing, gathering medicine, and helping heal the men. In one Virginia community a women’s group transformed an abandoned hotel into a hospital, and women in Georgia created the Atlanta Hospital Association which collected supplies to distribute to hospitals in Virginia. Some women in Virginia opened their homes to wounded soldiers, and members of the Ladies Tennessee Hospital and Clothing Association recruited women to serve as nurses in Virginia.[18]

Civil War nurses undertook a number of tasks beyond what would today be considered nursing. Some visited soldiers in the hospitals to help keep their spirits up. Others procured and prepared food for the patients. Some undertook the tasks associated with the actual care of the soldiers, though this part of the job threatened many women’s notions of ladyhood, especially in the South, so some were reluctant to participate in this aspect of nursing. As Faust has argued, gender prescriptions of the time prevented nursing from becoming a true avenue for female progress in the South because too many women there adhered to notions that prevented them from expanding their sense of self-worth and seeking equality.[19]

In the North, women’s efforts in nursing led to formal networks that eventually culminated in the creation of the United States Sanitary Commission. Elizabeth Blackwell, the nation’s first female physician, followed the lead of England’s Florence Nightingale in the recent Crimean War (1853-1856) by pushing officials to consider the role of sanitation in the high mortality rates among the soldiers. Indeed, as historian Mark Neely has shown, for every man killed on a battlefield during the Civil War, two others died from diseases such as dysentery, diarrhea, malaria, and typhoid. Knowledge of sanitation and germ theory had reached the point that professionals like Blackwell were starting to realize that these diseases were caused by unsanitary and overcrowded conditions in the field and could best be prevented by ensuring access to clean water, healthy food, and fresh air.[20] To help solve this problem Blackwell created the Women’s Central Association of Relief and she and fellow reformer Dorothea Lynde Dix began recruiting and training women to serve as nurses. The group also supervised the collection efforts of a number of soldiers’ aid societies.

The women continued these efforts in cooperation with the male leaders of U.S. Sanitary Commission (USSC) after the federal government finally responded to their calls and created the organization to oversee sanitation efforts throughout Union camps. Local governments throughout the North began to create sanitary commission chapters which were led by men but relied upon women for most of the work in gathering and distributing supplies and performing nursing duties.[21] A similar organization, the Western Sanitary Commission, developed to serve soldiers from the midwestern and western states, and the two organizations soon began to compete for women’s assistance. This competitive environment led to jealousy and rumors of mismanagement as well as tension between the men who led these groups and the local women who did most of the work.

Women members of the Soldiers’ Aid Society of the U.S. Sanitary Commission stand in front of the Society’s offices on Bank (West 6th Street) in 1865.

Photograph Courtesy of the Western Reserve Historical Society at Case Western Reserve University

Centralization of collection efforts also made it hard for local societies to convince people to give money and goods since they could no longer ensure that those contributions would go directly to soldiers from their particular community. Unfortunately, the competition and pressure eventually began to discourage women from engaging in organized sanitary work across the North. Even so, the women who did participate helped make the Sanitary Commission the most successful aid society of the Civil War with over ten thousand branch societies. These branches collected nearly five million dollars in cash and over fifteen million dollars’ worth of goods, mostly through “Sanitary Fairs” they hosted in major cities throughout the northern states.[22]

Given the longstanding distrust of centralization and persistent attitude of localism in the South, no overarching organization like the Sanitary Commission developed there. In some cases, southern soldiers’ aid societies worked in cooperation with local and state governments. In such cases the women worked out arrangements where the government would supply raw materials and the women would supply the labor to manufacture the finished goods. Even these efforts were localized, however, not going higher than the state level. As Scott has shown, the localism that prevailed throughout the South proved detrimental in the long term. Confederate women remained “intent on providing for the men from home,” ultimately paying “a high price in efficiency for their insistence on local control.”[23]

SOLDIERS’ AND WOMEN’S AID SOCIETIES AFTER THE WAR

As the war came to an end and the nation began to rebuild, the women of the aid societies had to shift their focus back to peacetime efforts. In the North, many of the societies transformed into mutual relief agencies that worked to help veterans and their families apply for pensions and readjust to civilian life. They helped provide for disabled soldiers and their families in many cases, especially when war-related disabilities prevented the soldiers from returning to their jobs. In both regions, some women continued to work as nurses after the war. Others simply ceased their work once the war ended, content that their wartime efforts demonstrated their patriotism.

Throughout the South, women who had worked so hard to keep the men going during the long fight took on the task of rescuing their image once they lost the war. Even before the war ended, the women transformed their aid societies into memorial associations and began creating Confederate cemeteries and erecting monuments to celebrate their veterans. These memorial associations established the Memorial Day holiday, decorating the graves of Confederate soldiers with flowers and flags in the spring. As with much of their wartime work, these efforts allowed women to remain safely in their prescribed domestic sphere, since caring for the graves of the fallen fell safely in the realm of their work as caretakers.

Historians have yet to truly assess the economic scope of women’s contributions to the Civil War. According to Scott, “Though women’s labor was essential to the maintenance of both armies, no economic historian has tried to assess its importance for the overall conduct of the war.”[24] It is clear, however, that women’s efforts prolonged the war. As Scott points out, the irony is that “if women on both sides had kept closer to their assigned sphere and let the two governments muddle on without their labor, the short war which so many had predicted might indeed have occurred, and nearly everyone would have been better off.”[25]

The social impact of women’s efforts rivals, if not surpasses, the economic impact. To begin with, women activists in the North played a role in changing the goals of their leaders, most notably through the Women’s National Loyal League. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony founded this society in early 1863 in response to their frustration over the limitations of President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. Abolitionists before the war, these women and many of their associates were disappointed that the President did not take a strong enough stand against slavery, and they banned together through groups such as the Loyal League to demonstrate to Congress the level of public support for immediate emancipation and the complete abolition of slavery.[26] Many of the aid societies joined with local chapters of the Women’s National Loyal League to push for this important goal. Similarly, wartime work gave women the confidence to push for their own rights. Many of these women went on to join suffrage societies after the war, using their legacy of sacrifice and leadership during the war to insist that they should be allowed to vote. Some even went so far as to argue that they should be allowed to run for political office.

THE LEGACY OF SOLDIER’S AND WOMEN’S AID SOCIETIES

Historians disagree on the extent to which women’s efforts during the Civil War changed their lives in the long run. After the war, most willingly returned to their domestic sphere, if they had actually left it at all. Particularly in the South, most women eagerly embraced their return to the home and worked actively to prop up the gendered notions of southern men as strong and capable providers. They made it their mission to salve the emotional wounds of their men and reassure them of their manhood.[27]

Even so, some historians have highlighted instances of southern women stepping beyond the boundaries of their traditional sphere. Beyond volunteering as nurses at a time in which that profession was seen as questionable for their sex, some began to openly and vocally question military and political decisions and moves. Others who were forced by the exigencies of war to operate the family farms and plantations took pride in how well they managed without the men and developed some sense of independence.[28]

For most northern women, participation in wartime efforts was an extension of their antebellum work in reform societies, and their work during the war intensified their efforts to expand the boundaries given to them by society. For many of them, work in the aid societies had a political dimension. According to Seidman, “the war intensified the political significance of women’s information and support networks, and how women’s activities helped to shape the political mobilization of the region” and it “reconfigured Northern women’s understanding of their political identities in both their own neighborhoods and in the nation as a whole.” Their work with the federal government through the Sanitary Commission in particular gave women a “sense of direct participation in the nation’s work” and allowed them an opening into regional political arenas. This led them to see and articulate their status in the nation in new and empowering ways.[29] When all was said and done, according to Scott, “on both sides the war allowed women to hone organizational and political skills which had been a long time in the making.”[30] They had displayed patriotism and loyalty and they expected to be recognized for it. Whether they stepped out of the domestic sphere or not, returned to it or not it is clear that women had done things they had never done before and that they were not going to go backwards from that.

- [1] Wharton, Katherine Johnson Brinley, Diaries Collection No. 1861, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

- [2] Anne Firor Scott, Natural Allies: Women's Associations in American History (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992), 68.

- [3] Nick Streifel, “Crisis Management during the American Civil War: The Hartford Soldiers' Aid Society,” Connecticut History.Org, (University of Connecticut Digital Media Center,University of Connecticut Librariesand theRoy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Mediaat George Mason University, n.d.) https://connecticuthistory.org/crisis-management-during-the-american-civil-war-the-hartford-soldiers-aid-society/, accessed June 10, 2019.

- [4] “Soldier's Aid Society,” Encyclopedia of Cleveland History (Center for Public History & Digital Humanities at Cleveland State University, 2017), (https://clevelandhistorical.org/items/show/264#.WTAzZMa-LOQ, accessed June 10, 2019.; Lisa M. Smith, “Northern Women,” in Lisa Tendrich Frank, ed., Women in the American Civil War, 2 vols. (Santa Barbara: ABC CLIO, 2008), 1:43.

- [5] Scott, Natural Allies, 62.

- [6] Rachel Filene Seidman, “‘We Were Enlisted for the War’: Ladies' Aid Societies and the Politics of Women's Work During the Civil War,” in Making and Remaking Pennsylvania's Civil War, William Blair and William Pencak, eds. (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press: 2001), 61.

- [7] Lindsey R. Peterson, “‘Iowa Excelled Them All’: Iowa Local Ladies' Aid Societies on the Civil War Frontier, 1861-1865,” in The Middle West Review: An Interdisciplinary Journal about the American Midwest in 3, no. 1 (Fall 2016): 54-60.

- [8] Robert W. Schoeberlein, “A Fair to Remember: Maryland Women in Aid of the Union,” Maryland Historical Society 90, no. 4 (Winter 1995): 469.

- [9] Patricia Richard, “Union Homefront,” in Lisa Tendrich Frank, ed., Women in the American Civil War, 1:77.

- [10] Ella Forbes, African American Women During the Civil War (New York: Garland Publishing: 1998), 93-101; Scott, Natural Allies, 67.

- [11] Seidman, “We Were Enlisted for the War”, 63.

- [12] George Rable, Civil Wars: Women and the Crisis of Southern Nationalism (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991); Scott, Natural Allies, 69-70.

- [13] Seidman, “We Were Enlisted for the War”, 68.

- [14] Scott, Natural Allies, 59.

- [15] Richard, “Union Homefront”, 77; “Throughout the war, the (Columbus Ladies Aid) Society held picnics, sanitary fairs or bazaars, and Tableaux Vivants to raise money. Tableaux vivants “living images” were a popular form of amateur entertainment. “Actors” were placed in a static position reminiscent of a particular historical event with the idea of bringing the image to the viewers minds in a three-dimensional form. Songs and poems often accompanied these scenes.” From OhioStatehouse.org, http://www.ohiostatehouse.org/Assets/Files/1000025.pdf , accessed June 10, 2019.

- [16] Andrea R. Foroughi, “Morale,” in Lisa Tendrich Frank, ed., Women in the American Civil War, 2:397.

- [17] Drew Gilpin Faust, Mothers of Invention: Women of the slaveholding South in the American Civil War, 1997 Vintage Books ed. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), 93.

- [18] Ibid., 93-94.

- [19] Ibid.,102-13.

- [20] Mark Neely, The Civil War and the Limits of Destruction (Boston: Harvard University Press, 2007).

- [21] Peterson, “Iowa Excelled Them All”, 52, 58.

- [22] Smith, "Northern Women", 43.

- [23] Scott, Natural Allies, 70.

- [24] Ibid., 58.

- [25] Ibid., 72.

- [26] Seidman, “We Were Enlisted for the War”, 71.

- [27] LeeAnn Whites, The Civil War as a Crisis in Gender: Augusta, Georgia, 1860-1890 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2000).

- [28] Foroughi, "Morale, 398.

- [29] Seidman, “We Were Enlisted for the War”, 62.

- [30] Scott, Natural Allies, 73.

If you can read only one book:

Frank, Lisa Tendrich, ed. Women in the American Civil War, 2 vols. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC CLIO, 2008.

Books:

Attie, Jeani. Patriotic Toil: Northern Women and the American Civil War. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998.

Boccardi, Megan. “Southern Women,” in Lisa Tendrich Frank, ed., Women in the American Civil War, 2 vols. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC CLIO, 2008, 1:67-73.

Cox, Karen L. “Aid Societies,” in Lisa Tendrich Frank, ed., Women in the American Civil War, 2 vols. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC CLIO, 2008, 1:96-97.

————. “Ladies' Memorial Associations,” in Lisa Tendrich Frank, ed., Women in the American Civil War, 2 vols. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC CLIO, 2008, 2:367-8.

Faust, Drew Gilpin. Mothers of Invention: Women of the slaveholding South in the American Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

Forbes, Ella. African American Women During the Civil War. New York: Garland Publishing, 1998.

Foroughi, Andrea R. “Moral,” in Lisa Tendrich Frank, ed., Women in the American Civil War, 2 vols. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC CLIO, 2008, 2:397-400.

Gallman, J. Matthew. “Voluntarism in Wartime: Philadelphia's Great Central Fair,” in Maris A. Vinovskis, Toward a Social History of the American Civil War: Exploratory Essays. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990, 93-116.

Giesberg, Judith. Army at Home: Women and the Civil War on the Northern Home Front. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

Kehoe, Karen A. “Wounded, Visits to,” in Lisa Tendrich Frank, ed., Women in the American Civil War, 2 vols. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC CLIO, 2008, 2:597-9.

Neely, Mark. The Civil War and the Limits of Destruction. Boston: Harvard University Press, 2007.

Peterson, Lindsey R. “‘Iowa Excelled Them All’: Iowa Local Ladies' Aid Societies on the Civil War Frontier, 1861-1865,” The Middle West Review: An Interdisciplinary Journal about the American Midwest 3(1) Fall 2016: 49-70.

Richard, Patricia. “Union Homefront,” in Lisa Tendrich Frank, ed., Women in the American Civil War, 2 vols. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC CLIO, 2008, 1:74-79.

Schoeberlein, Robert W. “A Fair to Remember: Maryland Women in Aid of the Union,” Maryland Historical Society 90, no.4 (Winter 1995): 467-88.

Scott, Anne Firor. Natural Allies: Women's Associations in American History. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992.

Seidman, Rachel Filene. “‘We Were Enlisted for the War’: Ladies' Aid Societies and the Politics of Women's Work During the Civil War,” in William Blair and William Pencak, eds. Making and Remaking Pennsylvania's Civil War. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press: 2001, 59-79.

Streater, Kristen. “Civilian Life,” in Lisa Tendrich Frank, ed., Women in the American Civil War, 2 vols. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC CLIO, 2008, 2:170-4.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

“Soldier's Aid Society of Northern Ohio” is an entry describing the history of this soldiers’ aid society published by Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, at Case Western Reserve University.

“Soldier's Aid Society” describes the history of the Soldier’s aid Society of Northern Ohio published by Cleveland Historical an application developed by the Center for Public History +Digital Humanities at Cleveland State University.

“First Annual Report of the Ladies' Springfield Soldiers Aid Society” reproduces their 1862 annual report published by Illinois During the Civil War, at Northern Illinois University.

Kristin Leahy, “Women During the Civil War, 1860-1864,” in Historical Society of Pennsylvania, December 2012.

“Ladies Union Aid Society” provides a brief history of the Ladies Union Aid Society of St. Louis Missouri Published by St. Louis Community College.

Catherine Fitzgerald, “Female Benevolent Societies” is an entry in the South Carolina Encyclopedia published by South Carolina Humanities and a variety of other organizations.

“The Civil War Homefront” is an entry published by the Wisconsin Historical Society.

Nick Streifel, "Crisis Management during the American Civil War: The Hartford Soldiers' Aid Society" published by Connecticut History.Org.

Kerry L. Bryan, “Civil War Sanitary Fairs” is an entry in the Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia published by the Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for the Humanities at Rutgers University-Camden.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.